The goal of cancer therapy is to destroy the cancer cells while minimizing side effects and damage to the rest of the body. Common types of treatment include surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and radiation therapy. Often combined with surgery or drugs, radiation therapy uses high-energy X-rays to harm the DNA and other critical processes of the rapidly-dividing cancer cells.

New innovations in radiation therapy were the focus of a recent episode of the Sirius radio show "The Future of Everything." On hand was Stanford's Billy Loo, MD, PhD, a professor of radiation oncology, who spoke with Stanford professor and radio host Russ Altman, MD, PhD.

Radiation has been used to treat cancer for over a century, but today's technologies target the tumor with far greater precision and speed than the old days. Loo explained that modern radiotherapy now delivers low-dose beams of X-rays from multiple directions, which are accurately focused on the tumor so the surrounding healthy tissues get only a small dose while the tumor gets blasted. Radiation oncologists use imaging -- CT, MRI or PET -- to determine the three-dimensional sculpture of the tumor to target.

"We identify the area that needs to be treated, where the tumor is in relationship to the normal organs, and create a plan of the sculpted treatment," Loo said. "And then during the treatment, we also use imaging ... to see, for example, whether the radiation is going where we want it to go."

In addition, oncologists now implement technologies in the clinic to compensate for motion, since organs like the lungs are constantly moving and patients have trouble lying still even for a few minutes. "We call it motion management. We do all kinds of tricks like turning on the radiation beam synchronized with the breathing cycle or following tumors around with the radiation beam," explained Loo.

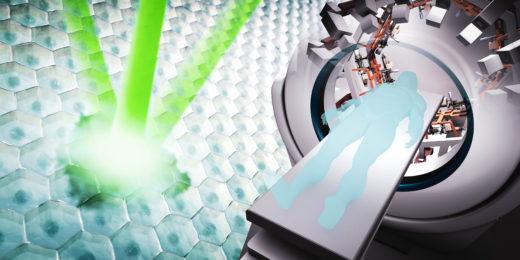

Currently, that is how standard radiation therapy works. However, Stanford radiation oncologists are collaborating with scientists at SLAC Linear Accelerator Center to develop an innovative technology called PHASER. Although Loo admits that the acronym was inspired because he loves Star Trek, PHASER stands for pluridirectional high-energy agile scanning electronic radiotherapy. This new technology delivers the radiation dose of an entire therapy session in a single flash lasting less than a second -- faster than the body moves.

"We wondered, what if the treatment was done so fast -- like in a flash photography -- that all the motion is frozen? That's a fundamental solution to this motion problem that gives us the ultimate precision," he said. "If we're able to treat more precisely with less spillage of radiation dose into normal tissues, that gives us the benefit of being able to kill the cancer and cause less collateral damage."

The research team is currently testing the PHASER technology in mice, resulting in an exciting discovery -- the biological response to flash radiotherapy may differ from slower traditional radiotherapy.

"We and a few other labs around the world have started to see that when the radiation is given in a flash, we see equal or better tumor killing but much better normal tissue protection than with the conventional speed of radiation," Loo said. "And if that translates to humans, that's a huge breakthrough."

Loo also explained that their PHASER technology has been designed to be compact, economical, reliable and clinically efficient to provide a robust, mobile unit for global use. They expect it to fit in a standard cargo shipping container and to power it using solar energy and batteries.

"About half of the patients in the world today have no access to radiation therapy for technological and logistical reasons. That means millions of patients who could potentially be receiving curative cancer therapy are getting treated purely palliatively. And that's a huge tragedy," Loo said. "We don't want to create a solution that everyone in the world has to come here to get -- that would have limited impact. And so that's been a core principle from the beginning."

Photo by ZIPNON