Diabetics are at heightened risk for COVID-19 complications, it's known. But the connection might run in two directions: COVID-19 may itself kick off or exacerbate diabetes.

A new study shows that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, selectively attacks the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, the critical hormone that regulates our circulating blood-sugar levels. The loss of these pancreatic cells, known as beta cells, is the defining feature of type 1 diabetes, understood to be triggered when the body's immune system, for unknown reasons, launches an unprovoked attack on those cells.

The pancreas is two organs in one. One part spews fierce digestive juices. The other part contains several cell types, about 70% of which are beta cells.

Until very recently, the pancreas wasn't believed to be a target of SARS-CoV-2, Stanford cell biologist Peter Jackson, PhD, told me. Nor was there any reason to think that within this organ, beta cells were at particular risk, he said.

But in the new study, led by Jackson and published in Cell Metabolism, the researchers examined pancreatic samples from nine patients who died from severe COVID-19-related complications. Samples from seven of those people tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

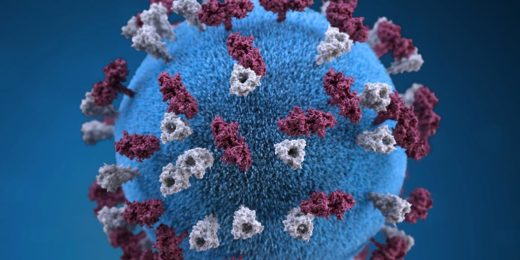

The study also showed that SARS-CoV-2 preferentially targets living human beta cells, as opposed to other pancreatic cell types, in laboratory glassware and -- importantly -- that it suppresses insulin secretion. The virus infected other pancreatic cell types in a lab dish, too, but it preferentially infected and killed the beta cells. Just incubating beta cells with the virus's spike protein -- the external feature of the virus that attaches to cells to begin the infection process -- was enough to activate beta cells' internal cell-suicide apparatus, Jackson and his colleagues found.

Two hands for beginners

It's known that SARS-CoV-2's ability to infect cells in the upper and lower respiratory tract (nose, throat and lungs), heart, kidney, and small intestine depends on the presence, on the surfaces of those cells, of a protein called ACE2. Nature didn't sprinkle ACE2 molecules on our cells so they could serve as welcome mats for viruses. This protein is important for regulating blood pressure. SARS-CoV-2 has coopted ACE2 to use as an entry dock.

Because ACE2 isn't abundant on beta cells, it was previously assumed those cells are unlikely to succumb to viral entry. But ACE2 doesn't act alone.

It turns out ACE2 has several different kinds of helpers, known as co-receptors. One is a molecule called NRP1 that Jackson's team found was plentiful on beta cells. NRP1 is also found in abundance in the brain, kidney and other tissues and has been shown to play a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection of olfactory epithelia, the tissue whose loss is responsible for the loss of sense of smell, he said.

In the study, NRP1 emerged as a central player on the beta cell viral-entry team.

"If you try to pick up a basketball with only one hand, it's tough. Two hands are much better," he said. "How the two hands work together -- or, for that matter, even how many hands there are -- isn't yet clear, but one of those hands seems to be NRP1," said Jackson.

While there are no approved drugs for inhibiting NRP1, the investigators had access to and used an experimental compound (called EG0229) to block NRP1, substantially diminishing SARS-CoV-2's ability to infect human beta cells in a lab dish.

The researchers also showed that incubating beta cells with the NRP1 blocker prior to adding SARS-CoV-2 to the dish prevented infection and cell death, in addition to restoring the cells' insulin-secretion capability.

The pancreas is an extraordinarily vascularized (permeated with blood vessels) organ that carefully assesses supplies of sugar and other digestible substances in the bloods so it can time its squirts of digestive juices and insulin, Jackson noted.

"Once the virus is in the lung, there's plenty of surface area for it to get out into the bloodstream," he said. You might expect highly vascularized tissues including the pancreas, kidneys, and the most vascularized tissue of all -- the brain -- to be very vulnerable.

Even after patients recover from severe COVID-19, the virus may cause long-term damage to these vascularized tissues," Jackson said. "But we don't yet understand what complications these patients may experience later on. The clinical importance here is unusually clear."

Photo by Nertuz