It sounds like a magic potion straight out of a science-fiction novel: Two color-shifting compounds from a substance so rare it's estimated to cost $39 million per gallon could help kill stubborn bacterial infections.

But this isn't science fiction. The substance is venom, and it comes from a Mexican scorpion that's roughly the size and color of a peanut shell.

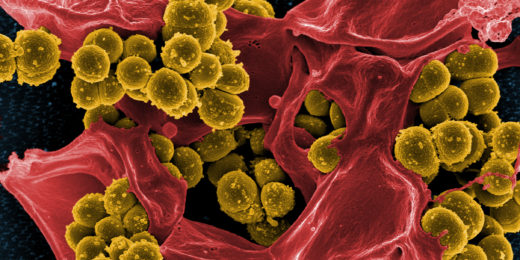

As a Stanford News story explains, researchers discovered this scorpion's venom contains two color-changing compounds that can kill the bacteria responsible for staphylococcus and drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Lourival Possani, PhD, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, is a scorpion venom expert, and he's devoted 45 years of his life's work to collecting scorpions and identifying compounds in their venom that could be developed into healing drugs.

Venom from the eastern Mexican scorpion species, Diplocentrus melici, is hard to come by, he explained.

"The collection of this species of scorpion is difficult because during the winter and dry seasons, the scorpion is buried," Possani said. "We can only find it in the rainy season."

Once scorpions are found and caught, they must be milked to release their venom. Milking a scorpion is about as difficult and fruitful as it sounds -- you stimulate its tail carefully with mild electrical pulses to encourage it to release venom. The scorpions release tiny droplets of venom at a time, which makes this poison some of the most valuable liquid there is.

While studying the venom of the scorpion species D. melici, Possani and his team saw the venom change color when exposed to air, shifting from clear to shades of brown. Delving deeper into the venom's chemical components, they found two curious chemical compounds that shifted color in the presence of air -- one turning red, the other turning blue.

To identify the color-shifting compounds, Possani contacted Stanford chemist Richard Zare, PhD, and shared their tiny venom samples with his team.

"We only had 0.5 microliters of the venom to work with," Zare said. "This is ten times less than the amount of blood a mosquito will suck in a single serving."

Zare and his research team discovered the color-changing compounds were two ring-like molecules with antimicrobial properties (called benzoquinones) that had never been described before. The compounds were structurally similar, but the molecular branches of the red compound contain an oxygen atom, the blue one a sulfur atom.

After isolating the compounds from the scorpion venom, Zare and his team synthesized them in the lab.

"If you depended only on scorpions to produce it, nobody could afford it, so it's important to identify what the critical ingredients are and be able to synthesize them," Zare said.

The next step was verifying that the synthesized versions of the compounds could kill bacteria as the scorpion venom's compounds did.

Zare's team sent their lab-made benzoquinones to pathologist Rogelio Hernández-Pando, MD, of the Salvador Zubirán National Institute of Health Sciences and Nutrition in Mexico City.

Hernández-Pando's team tested the compounds on tissues and in mice and found the red compound successfully killed staphylococcus bacteria, and the blue compound killed both normal and multi-drug-resistant strains of the bacteria that causes tuberculosis.

"We found that these compounds killed bacteria, but then the question became 'Will it kill you, too?'" Zare said. "And the answer is no: Hernández-Pando's group showed that the blue compound kills tuberculosis bacteria but leaves the lining of the lungs in mice intact."

In the future, the Stanford and Mexican research teams plan to continue their work together to see if the two compounds can be made into therapeutic drugs. They also aim to study why scorpions have these compounds in their venom, and purpose they may serve.

"We have no idea why the scorpion makes these compounds." Zare said. "There are more mysteries."

Photo of Zare and scorpion by Edson N. Carcamo-Noriega