High-grade serous ovarian cancer is a sneaky disease that is often not diagnosed until it has reached an advanced state when it is difficult to treat successfully. For years, physicians and researchers have worked to identify new therapeutic targets and markers that can give clues to an individual patient’s prognosis. Now, new findings from a Stanford study should help get them closer.

Immunologist and cancer biologist Veronica Gonzalez, PhD, and cancer biologist Wendy Fantl, PhD, along with gynecologist and oncologist Jonathan Berek, MD, and microbiologist and immunologist Garry Nolan, PhD, analyzed at the single-cell level more than 800,000 ovarian cancer cells from 17 newly diagnosed patients at an unprecedented level of specificity. They published their results in Cell Reports.

"Until now, high-grade serous ovarian cancer has been studied by analyzing homogenized tumor samples," Gonzalez told me and further explained:

In this study, we instead analyzed intact single cells. This allowed us to identify rare cell subsets that would have otherwise been lost in bulk homogenates. Although we identified 56 cell types that are shared by most of the tumors, we also found a pre-existing rare cell subtype that correlated strongly with early relapse. Additionally, we identified a second, hybrid cell type with dual characteristics of cells within the tumor and of cells with the ability to metastasize. To date such 'half-way' or hybrid cells had only been inferred to exist from tumor datasets or been found in animal models and cell lines.

For their work, Fantl and her colleagues used a technique called CyTOF that was developed in Nolan’s lab to analyze the tumor cells. CyTOF allows cells to be sorted in one experiment into different categories based on the expression of more than 40 proteins.

"The surprising result of these studies is that, despite the many different genetic and environmental influences that likely led to cancer in these women, the cancers have a reiterating, repeating 'structure,'" said Nolan. "These studies underscore (as we have seen in other oncologies) the fact that cancer is not infinitely variable — it has boundaries and a memory of the tissues from which it arose. That memory defines the boundaries of what it can become. Epigenetics likely plays a huge role in this process."

The researchers used CyTOF to confirm the fact that tumors with very diverse cell types tend to have a poorer prognosis — most likely because some of those cells are busily acquiring mutations that help them metastasize or resist the effects of anti-cancer drugs. In particular, Fantl and her colleagues identified a subset of tumor cells that co-express three proteins — vimentin, HE4 and cMyc — often found on metastatic cells. Women whose tumors had an increased number of these cells were at a high risk of early relapse, the researchers found.

"We hypothesize that the combination of these three metastasis-inducing proteins expressed together in the same cells will ensure these cells are not only strongly predisposed to resist platinum chemotherapy treatment but are susceptible to further mutation to enable them to escape the confines of the primary tumor," Fantl told me. "The greater the number of such cells within a given tumor, the higher the chance of a mutation that enables (a clone of) these cells to metastasize and thus correlates with a poor prognosis."

Fantl, Gonzalez and their colleagues are hopeful that their study will not only lead to new assays that could predict which women are most likely to have poorer outcomes (and thus may benefit from rapid, more aggressive treatment earlier in the course of their disease) but also to the identification of steps leading to metastasis that could be targeted by future drug development.

"Single cell analysis allows the identification of rare and subtly different cell subtypes that are lost if the tumor is ‘mashed up,'" Fantl told me. "Studies like ours are critical to understanding how tumors evolve, metastasize and become resistant to drugs. Focusing drug therapies on reducing or eliminating such cells could significantly improve outcomes for this deadly disease."

Berek agreed:

These research findings will lead to a better understanding of the underlying biology of high-grade serous cancer — the most common type of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer — and this knowledge will be applied to the care of women diagnosed with and treated for these diseases. Being able to better predict the behavior of individual tumors will facilitate the development of improved targeted, personalized therapies and better management strategies for our patients.

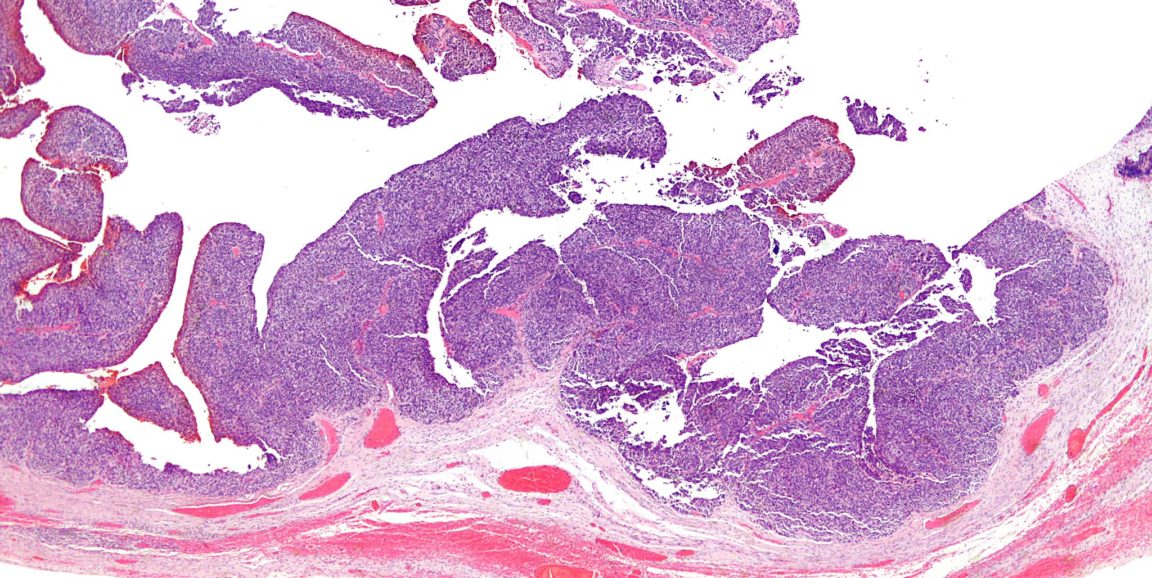

Image by Nephron