For Ron Gross, the transition from healthy middle-aged man to seriously ill patient in need of a bone marrow transplant happened almost instantaneously.

The day had started out simply enough. Gross, a resident of Las Vegas, drove to his local hospital to undergo a few routine tests before an upcoming cervical fusion. His blood work revealed abnormalities soon determined to be myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) -- a cancer of the bone marrow that affects the ability to make healthy blood cells.

His physician swiftly mapped out next steps: Gross would need an immediate transfusion of platelets to prepare him for the original spinal surgery, followed by 10-months of chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy began without a hitch. "At first everything seemed to be working," Gross recalled in a recent Department of Medicine article. However, things started to quickly unravel.

"I was needing supplementary infusions. My blood wasn't working out too good as far as the counts went," he continued. Soon, Gross was averaging about two to three transfusions per week of red blood and platelets.

It wasn't long before his physician suggested that he needed think about finding a donor for a bone marrow transplant. Gross began to do some research, ultimately deciding to continue his treatment at Stanford.

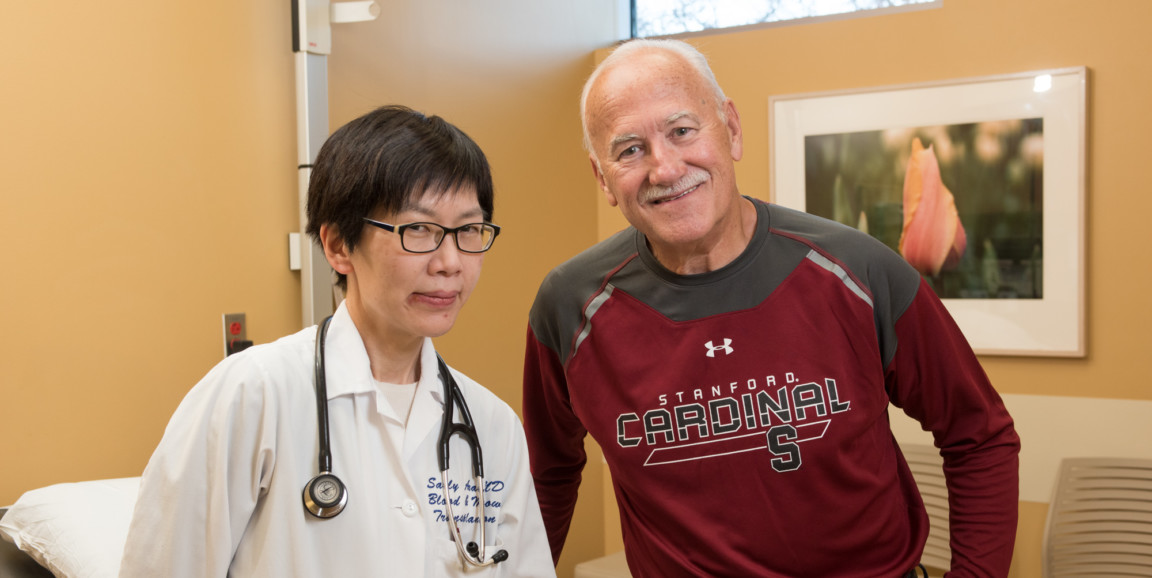

Sally Arai, MD, associate professor of medicine, became Gross's oncologist at Stanford. "He presented for transplant with high-risk disease," she explained. "What distinguished him was how very optimistic he was. He was just a lovely person from the beginning and very trusting."

Alongside Arai, Gross began the grueling search for a donor. He started -- as most patients do -- within his own family, but his siblings weren't deemed a fit. So, Arai and Gross turned their sights to the Be the Match Registry, where they eventually found a matching, unrelated donor who lived outside the U.S.

Gross received his bone marrow transplant in the winter of 2014. His recovery went seamlessly with no episodes of rejection, but he couldn't shake his lingering curiosity about the identity of his donor. The two struck up an anonymous correspondence -- international transplant rules dictate that donors and recipients can't learn the identity of one another until two years have passed -- sending unsigned letters and cards back and forth.

When the second anniversary of his transplant finally arrived, Gross rushed to the phone to dial the number he had been given by the registry. To his dismay, the line was busy. But as he hung up, his own phone began to buzz. Recipient and donor had tied up the phone lines trying to call each other. It was a serendipitous -- and fitting -- start to a lifelong friendship.

Gross's donor, Karolina Wierciak, is an artist who resides in Szczecin, Poland. She became an international organ donor in Germany to honor her cousin who had died from throat cancer. "Even though she is the CEO of her company, working long hours, she decided to drive 211 miles to Germany and donate her bone marrow for global distribution, a decision that saved my life," Gross said.

Today, the two remain in close touch via email, social media, and text. Gross and his family even traveled to Poland to spend time with Wierciak. When asked how he would introduce Wierciak to a friend or acquaintance, he didn't skip a beat: "I would introduce her as my sister Karolina and my hero."

Photo of Sally Arai and Ron Gross by Steve Fisch