Biophysicist Anthony Ricci, PhD, seems to spend a lot of time worrying about premature babies going deaf. It's not because he has a deaf child, or because he's a doctor who treats premature babies. He's not that kind of a doctor. But Ricci, a professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, and a self-confirmed lab rat, has seen firsthand how certain life-saving antibiotics can wreak havoc on what is his area of expertise -- the inner ear.

Using what he's discovered over decades of studying the biophysics of the inner ear, Ricci has joined forces with Alan Cheng, MD, a physician-scientist who treats children with hearing loss, to design a new version of an aminoglycoside -- a widely used antibiotic with that can cause deafness. In an article I wrote for the new issue of Stanford Medicine magazine, I tell the story of Ricci and Cheng's mission to translate basic science discoveries into better treatment for sick patients. As Ricci says in the story:

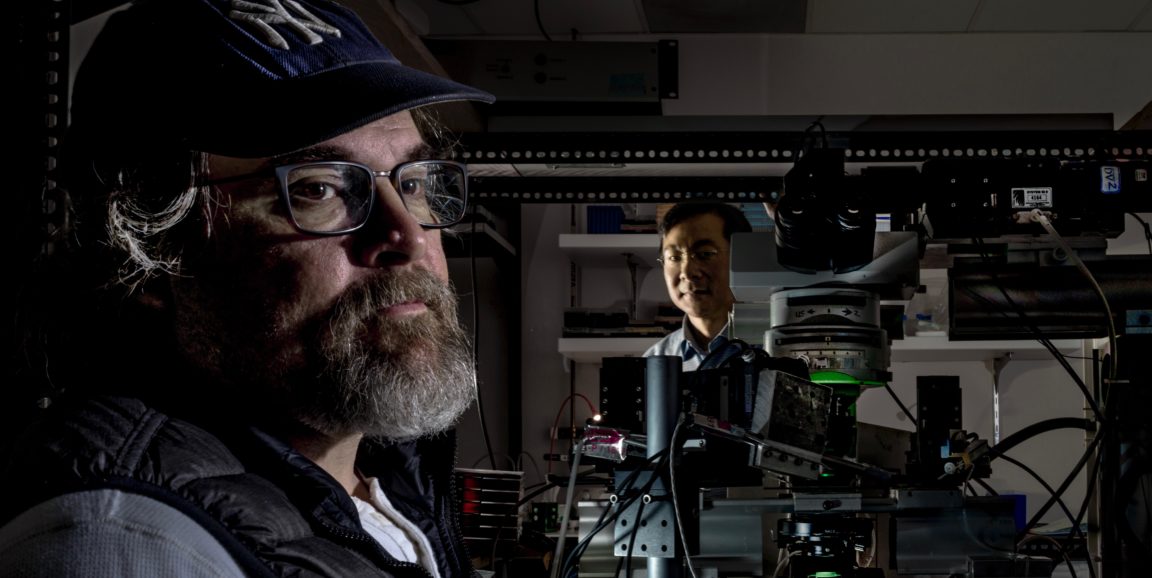

I never thought I'd be doing something like this,' says Ricci, a familiar sentiment for the Bronx-born son of a taxi driver who once thought school was a waste of time. He grins, pushing back his Yankees cap, and adds, 'What do I know about making a drug?'

Actually, by now, he knows quite a bit. Since the two scientists joined forces in 2008, they've built a team of drug development experts and completed two rounds of testing on 18 new antibiotic compounds. Of these 18 versions, three successful candidates have emerged for further study. They're now hopeful the third round of testing will be the charm.

Far too many people, including premature infants who need help staving off infections, are losing their hearing in order to save their lives, says Cheng. He sees this firsthand:

'When a drug causes hearing loss it is devastating, and it's especially disturbing when this happens to a young child, as they rely on hearing to acquire speech,' Cheng says. Despite this, aminoglycosides remain the 'go to' drug for treating life-threatening infections, a choice made by many physicians worldwide.

Developed in the 1940s, aminoglycosides such as gentamicin and streptomycin are not only still commonly used to treat tiny babies, they're one of the most widely used class of antibiotics to treat everything from cystic fibrosis to tuberculosis to any infection with an unknown cause.

They save untold lives, but they also cause hearing loss in about 20 percent of the patients who take them. Ricci is excited about the "cool" approach of using "very fundamental basic science research to actually translate to helping patients." But, he adds, figuring out how to design a drug, even when surrounded by experts, has proven to be extremely difficult.

'It's not always possible to see your basic science research make a difference in people's lives,' Ricci says. 'It's nice to be able to give back a little -- at least, I hope we can.'

Photo by Max Aguilera-Hellweg