It's the ultimate switcheroo. Stanford stem cell researcher Marius Wernig, MD, along with former postdoctoral scholar Koji Tanabe, PhD, and graduate student Cheen Ang, have shown it's possible to trigger human immune cells from a simple blood sample to abandon their calling and to instead convert, relatively quickly and efficiently, into human neurons with the genetic makeup of the person from whom the blood was obtained.

Far more than a biological party trick, the feat opens the door to the study of an unprecedented number of neurons from patients with complex disorders like schizophrenia and autism.

The researchers, who were able to generate as many as 50,000 neurons from 1 milliliter of either fresh or frozen blood, published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

As I describe in our release, even the scientists themselves were a bit surprised by their discovery:

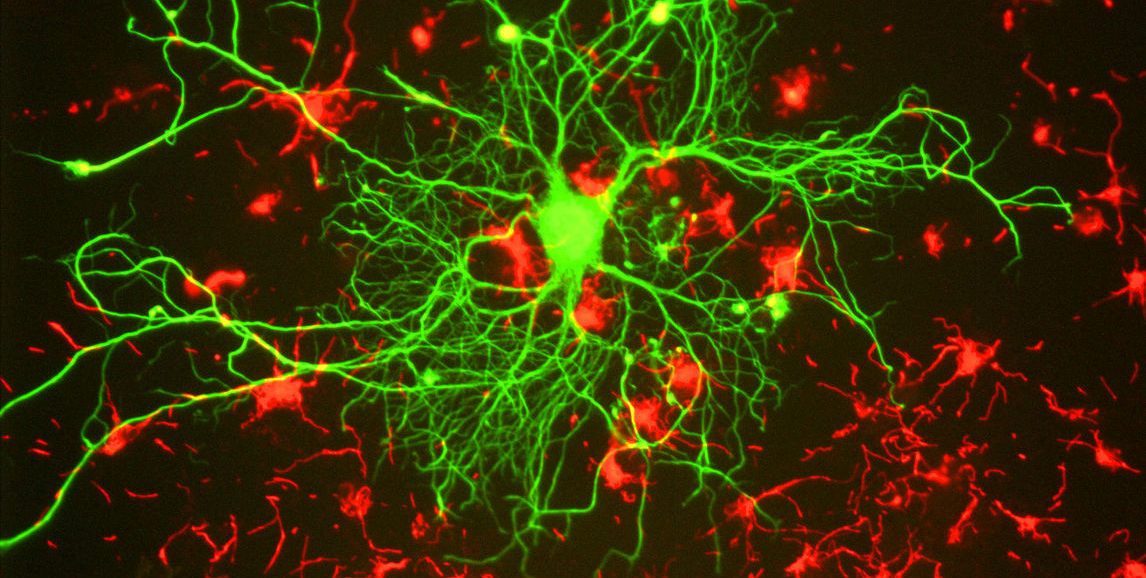

T cells protect us from disease by recognizing and killing infected or cancerous cells. In contrast, neurons are long and skinny cells capable of conducting electrical impulses along their length and passing them from cell to cell. But despite the cells' vastly different shapes, locations and biological missions, the researchers found it unexpectedly easy to complete their quest.

'It's kind of shocking how simple it is to convert T cells into functional neurons in just a few days,' Wernig said. 'T cells are very specialized immune cells with a simple round shape, so the rapid transformation is somewhat mind-boggling.'

Wernig, who is a member of Stanford's Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, and his colleagues were capitalizing on a technique called transdifferentiation that was first developed in Wernig's lab in 2010. In the earlier study, the researchers showed it was possible to directly convert mouse skin cells into mouse neurons without first inducing the cells to become pluripotent -- a step that had previously been thought to be indispensable to convince cells to change fates.

The researchers went on in subsequent years to show they could accomplish the same feat starting with human liver and skin cells. But liver and skin biopsies are invasive and uncomfortable, and yield only a relatively small number of cells per patient. Not so with blood.

As Wernig said in our release:

Blood is one of the easiest biological samples to obtain. Nearly every patient who walks into a hospital leaves a blood sample, and often these samples are frozen and stored for future study. This technique is a breakthrough that opens the possibility to learn about complex disease processes by studying large numbers of patients.

Large numbers of patients are critical for researchers wishing to study genetically complex mental disorders in order to suss out the relative contributions of dozens or more disease-associated mutations.

"We now have a way to directly study the neuronal function of, in principle, hundreds of people with schizophrenia and autism," Wernig told me. "For decades we've had very few clues about the origins of these disorders or how to treat them. Now we can start to answer so many questions."

Image courtesy of GerryShaw