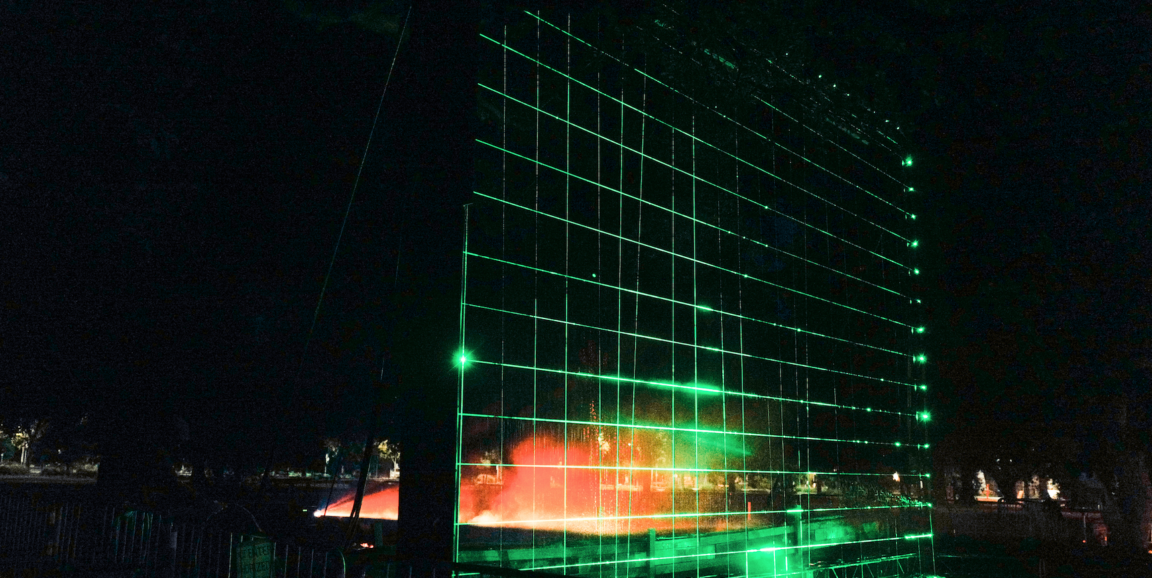

Rising 20 feet from the ground with lasers that cut a jade-green lattice of light spanning 30 feet across, The Frankenstein GRID: Stanford’s Monster of Modern Science is an art installation that stitches art and science together in a way viewers say is both beautiful and, at times, unsettling.

“The Monster," as creator and art curator Charlotte Thun-Hohenstein affectionately calls it, began to take shape about a year and a half ago when she received a grant from the Medicine and the Muse program to build the exhibit on the Stanford campus in honor of the 200-year anniversary of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein.

“The theme defining the whole project is 'stitches',” said Thun-Hohenstein, a graduate student in history at Stanford. “They are the ultimate metaphor of modern science — both healing and disfiguring, just as modern science is both healing and disfiguring the world, and they are iconic of the monster.”

The GRID is also symbolic. Gridlines are all that’s left when you strip a map of its features, Thun-Hohenstein explained. That’s why she views it as “a framework for interpreting the world,” our relationship to modern science and what it means to be human.

Looking up at the giant scaffold in the open space next to the building that houses the Anderson Collection, Thun-Hohenstein and I circled the seemingly sleeping giant. It was her idea to use create an interlaced grid of lasers as a “canvas” to display images of research and art that she curated from local and international scientists and artists, but many others helped make the vision a reality, she emphasized.

“We benefitted from a great deal of support and open-mindedness of the artists that I engaged. I am especially grateful to the many volunteers who showed up for parts of the construction process,” Thun-Hohenstein said. Just getting the 20 by 30 foot frame upright was no small feat, she explained, showing me a video of a team of people pulling in unison to hoist the scaffold into place.

Clouds of fog made from liquid glycerin worked well to make the lasers visible, Thun-Hohenstein explained, but they weren’t substantial enough to serve as a screen for the projected video. Daniel Cadigan, the GRID's technical director and a campus theater carpenter, came up with the idea to rain water from the top of the scaffold, making a video screen out of water. It also added a shimmering quality to the GRID, said Thun-Hohenstein.

For seven nights starting on June 4, the video, images and music of over 25 artists will be featured against the backdrop of the GRID in a free, two-hour show. Each night has its own theme that unites the research and art on display that evening.

On opening night, the theme was "Self" and featured several works including a video of yeast and human cells fusing together by researcher and artist Oron Catts set to an audio track by Stanford composer Andrew Watts. The work of bioartist François-Joseph LaPointe, PhD, Yulia Pinkusevich and several other researchers and artists were also featured.

The goal of the GRID is "to help people think about science, and also feel about science in a new way — almost an emotional way,” Thun-Hohenstein said. “In the story of Frankenstein, the monster is Victor Frankenstein turning away from his creation and denying it the human connection is craves.”

Uniting art and science is an increasingly urgent need as humans are changing the environment, Thun-Hohenstein said. “Science will become a monster, or monstrous, if we don’t keep the human experience as part of it.”

Photo of the GRID by Michelle Chang