Kids are getting left behind in the latest wave of medical device invention, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is working to change that. That was the key message from Vasum Peiris, MD, in a presentation about the state of pediatric medical device development at the first Stanford Pediatric Innovation Showcase, held recently on campus.

The problem is that many devices are never approved for use in infants and children, said Peiris, the FDA’s chief medical officer for pediatrics and special populations. Pediatricians often use medical devices "off label," without formal testing in children, but this chewing-gum-and-bailing-wire approach has drawbacks, the worst of which is that, sometimes, there’s simply no way to use the most advanced technology in an infant or child.

Peiris presented data showing that, in the past decade, the problem has worsened: Medical innovation for grown-ups has accelerated, while the rate of new-device approvals for children has stayed flat.

"The gap is widening — our pediatric patients are becoming more vulnerable," Peiris said. "It's a misconception that adult approval must come first. When devices aren’t studied in kids from the very beginning, they don’t always get studied later."

Why the gap? Peiris explained that fewer kids get sick, so the market size for pediatric devices is smaller than for adults and the return on investment for device developers is lower. Small body size and physiologic differences between children and adults create unique design considerations. Because they're young, children need devices that will last decades. And the ethics of conducting research in kids can be more complicated, although avoiding studying children generates its own set of ethical problems.

To try to close the divide between children and adults, Peiris is leading FDA efforts to make the approvals process for pediatric devices more efficient. For instance, his team is expanding the capacity of the FDA’s breakthrough device pathway, an expedited approval route.

There’s also a need to focus on "patient values, not just P values," Peiris said, referencing the statistical cutoffs scientists use to decide whether results are clinically meaningful. "Sometimes P values don’t recognize what patients value — patients with no other options may be willing to take on high risks, for example. We need a process that understands their needs and is willing to focus on what is important to that patient." The FDA is seeing a significant increase in device applications that include patients' stories, he said, adding that explaining what patients value can also help convince insurers to cover new treatments.

Finally, because pre-market clinical trials are highly controlled, they don’t give a full picture of how devices work in the real world. To solve that problem, Peiris said, the FDA needs to shift to conducting both pre- and post-market clinical trials, with data reported both before and after a device is approved.

To further the conversation, Peiris and his colleagues are hosting a public meeting on pediatric medical device development August 13 and 14 at the FDA's campus in Silver Spring, Maryland. The event is free and registered attendees can participate in person or via webcast.

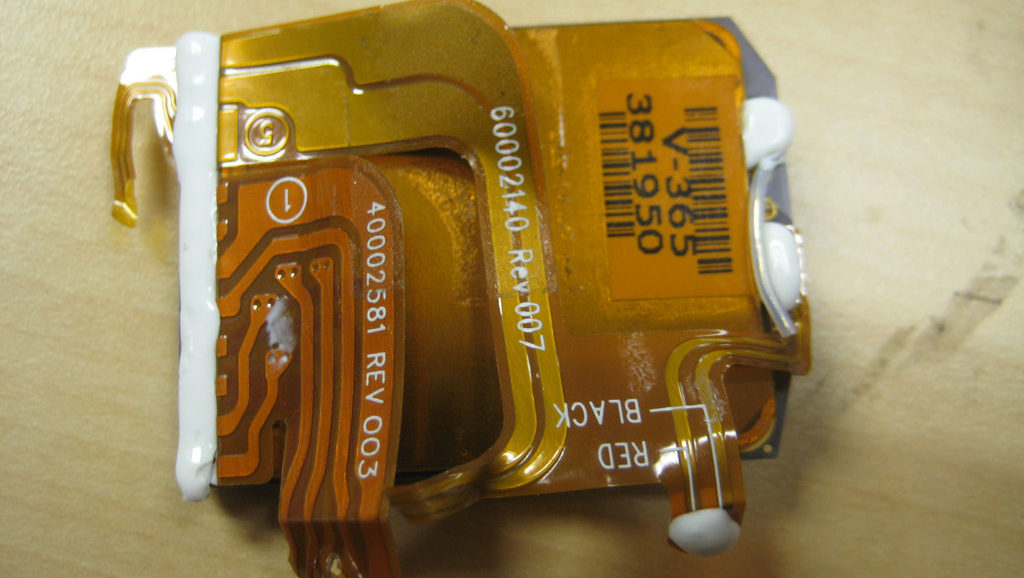

Photo of inner workings of a cardiac pacemaker by Travis Goodspeed