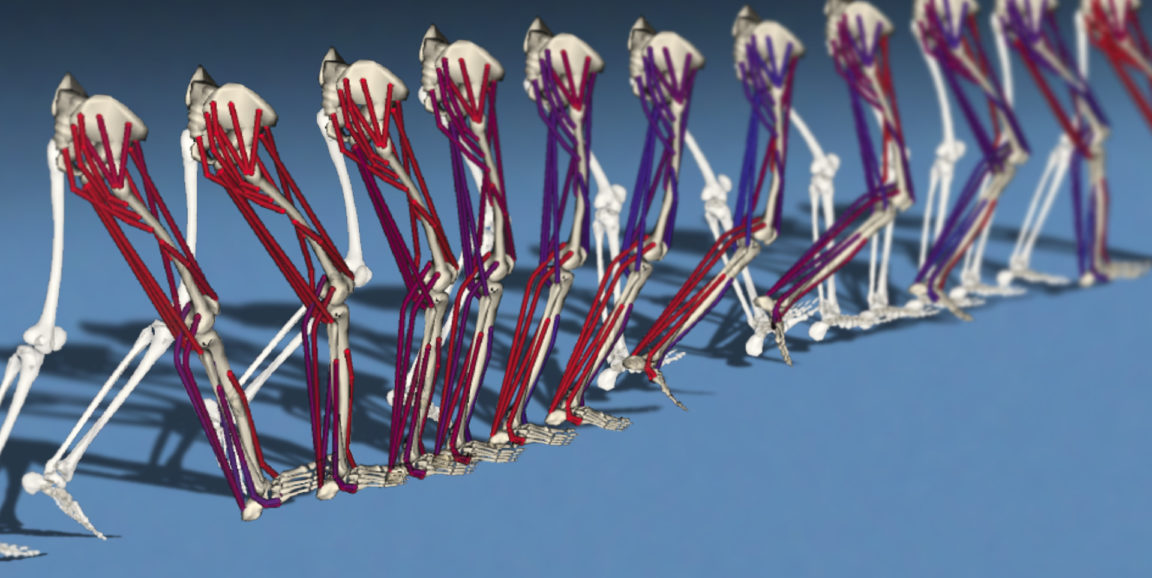

The contestant wastes no time. It swings a prosthetic leg violently forward, drags its other leg quickly behind, then collapses into the ground — but it’s okay. This athlete is computer generated, and what its creators learn from its fall could help them win a contest with a serious goal: designing better prosthetic limbs and helping patients adapt to them.

Łukasz Kidziński, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in bioengineering, cooked up the contest following the success of a similar event last year in which teams of academics, private-sector artificial intelligence researchers and enthusiasts competed to train virtual athletes to run through an obstacle course.

That first online contest stemmed from a basic problem Kidziński and colleagues faced. While researchers like his advisor, Scott Delp, PhD, a professor of bioengineering and mechanical engineering, know a great deal about how bones and muscles move, no one is quite sure how the brain controls complex processes like walking and running.

To close that gap, Kidziński hit on the idea of a competition, in which teams from around the world would compete to design artificial intelligence algorithms that would, along with virtual bodies informed by Delp’s data and models, learn to walk, run and eventually navigate obstacles. The winning algorithms, the researchers believed, could tell them something about how real people would learn to walk and run — or more to the point, how they would relearn to walk and run after surgery, although the first contest did not directly address that issue.

This year, he aimed higher.

“Last year was more of a proof of concept,” Kidziński says. “This year we want to get closer to medical applications.”

In this year’s version, teams now work with a body that includes a prosthetic leg, with the aim being to understand how people would learn to move again after losing a limb and gaining a protheses. Although no contestant has made it very far yet — teams are judged on how far their virtual competitors can walk from a starting point — Kidziński isn't worried. Last year around this time, no team had managed more than walking a few steps, and some fell flat on their faces, virtually speaking.

“It wasn’t obvious the problem would be solved,” Kidziński says, but solved it was. Although last year’s winner was perhaps not the most elegant runner, it made it through an obstacle course, in the process showing the approach could work.

“Compared to the first challenge this new challenge is a big step forward,” Kidziński says, but still he expects it will be solvable, not to mention enticing. Last year, the contest attracted 442 teams. Three weeks into this year’s contest, 100 teams have signed up to participate and made more than 500 entries so far.

After last year’s success, Kidziński hopes to get upwards of 1,000 participants, in part through expanded incentives. This year, Nvidia will award their top graphics processing units to the top three teams, and Google has offered cloud computing resources for teams who might otherwise find it difficult to take part.

But most important, Kidziński says, is that what was once a crazy idea — crowdsourcing algorithms to solve problems in biomechanics — has worked out so well that it could one day go from a virtual contest to helping real people in the real world.

Details on how to participate, including information on free resources to get started — not to mention win prizes and solve a significant medical challenge — are available at the project’s website.