After about a decade and a half (or, gulp, more?) on the stem cell beat, I've written a lot about those developmentally flexible cells that are responsible for everything from generating a human embryo after fertilization to responding quickly and efficiently to developmental cues or SOS signals from damaged tissue. They're truly amazing cells, and we're still trying to figure out exactly what makes them tick.

The study of stem cells relies in large part on the discovery of a cellular reprogramming process that allows researchers to create what are called induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells, from readily available cells like those in skin or blood. But the nuts and bolts of what happens during reprogramming remain somewhat mysterious.

Now microbiologist and immunologist Helen Blau, PhD, and postdoctoral scholar Thach Mai, PhD, have started to unveil the inner workings. They published their findings last week in Nature Cell Biology.

From my article:

The discovery creates a peephole into the black box of cellular reprogramming and may lead to new ways to generate iPS cells in the laboratory. It was made possible by the use of a unique laboratory model for reprogramming that tightly synchronizes the earliest steps of the process. 'This is a crucial regulator that would not have been discovered any other way,' said Helen Blau, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology. 'It appears within two hours of the initiation of reprogramming, and then it’s gone. But it’s absolutely critical. If we eliminate it, reprogramming doesn’t happen.'

The fact that reprogramming occurs at all in human cells captivated the world in 2007 when stem cell researcher Shinya Yamanaka, PhD, identified a panel of four proteins that, when applied externally to specialized cells like those from the skin or blood, could induce them to rewind their development and become stem cells. Since then, these four "Yamanaka factors" have been the cornerstone of decades of stem cell research.

Now Blau and Mai have shown that it's possible to replace one of the factors, Oct4, with another protein called NKX3-1. Cells exposed to NKX3-1 plus the three remaining factors reprogram as efficiently, and undergo the same molecular changes, as those exposed to the original four factors. Conversely, blocking the activity of NKX3-1 prevents any reprogramming by the Yamanaka factors. The researchers found that NKX3-1 is part of a cascade of reprogramming-specific events that are triggered within the cell by the external application of Oct4.

This discovery would not have been possible without a unique technique that synchronizes the first minutes and hours of reprogramming to allow for close study.

From our article:

In the new study, Mai fused human skin cells called fibroblasts to mouse embryonic stem cells. After fusion, factors in the developmentally flexible stem cell quickly and efficiently reprogrammed the fibroblast nucleus along a predictable, research-amenable timeline. The fused cells are called heterokaryons, and they enabled Mai and his colleagues to closely track patterns of gene expression and DNA modification during the first 24 hours of reprogramming.

The researchers have big plans for this heterokaryon model. According to Blau, who is the Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Foundation Professor and director of the Baxter Foundation Laboratory for Stem Cell Biology:

Our goal is to study all facets of the regulatory logic, or ‘grammar,’ that underlies cellular reprogramming to pluripotency. Reprogramming completely changes a cell’s fate. We want to understand the mechanistic and signaling pathways that mediate such a remarkable change.

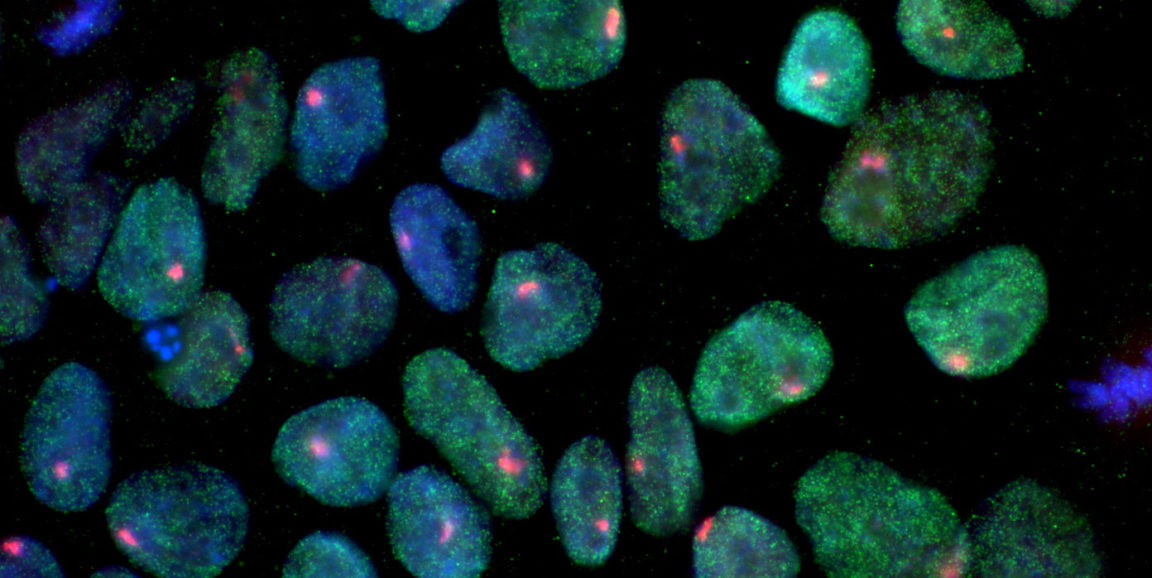

Photo of iPS cells courtesy of Thach Mai