I've been lucky in my life to have broken only one bone when I was 6 years old. The accident happened on the school playground when a classmate decided I was less fun to hang out with than another child who had yelled an invitation across the tarmac.

In a flash, my "friend" was running off to join them and I, who had been sitting on a seesaw seat high in the air counterbalanced by her weight, found myself inexplicably on the ground with an excruciating pain in my wrist. Clearly, this early betrayal still burns bright in my mind.

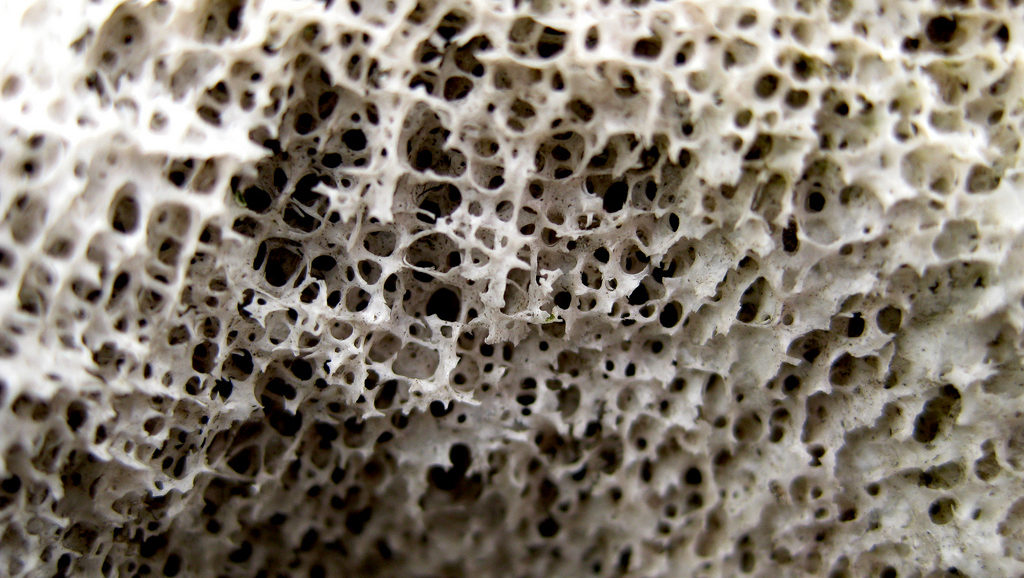

For many older Americans, however, bone health and fracture risk are everyday concerns. The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that two million people each year suffer a fracture, which accounts for about $19 billion in health care costs, and that 20 percent of seniors who break a hip die within one year. This is way more serious business than my playground incident. But it's not possible to predict at an early age who among us is likely to develop the bone-weakening disease.

Now developmental biologist Stuart Kim, PhD, has come up with an algorithm that may predict an individual's genetic risk of developing the condition based on their DNA sequence and other characteristics such as their sex, age and weight. It's the first inkling that it might be possible to proactively identify those at risk. He published the results of the study in PLOS ONE.

According to our release:

People deemed to be at high risk — about 2 percent of those tested — were about 17 times more likely than others to develop osteoporosis and about twice as likely to experience a bone fracture in their lifetimes. In comparison, about 0.2 percent of women tested will have a cancer-associated mutation in the BRCA2 gene, which increases their risk of breast cancer to about six times that of a woman without a BRCA2 mutation.

Knowing your risk in advance could help you take steps early in life to prevent the development of the condition.

As Kim explained:

There are lots of ways to reduce the risk of a stress fracture, including vitamin D, calcium and weight-bearing exercise. But currently there is no protocol to predict in one’s 20s or 30s who is likely to be at higher risk, and who should pursue these interventions before any sign of bone weakening. A test like this could be an important clinical tool.

Kim studied the health data and genome sequences of nearly 400,000 participants in the UK Biobank to develop and test the algorithm. He's now working to arrange clinical trials to investigate whether elite athletes and select members of the military identified by the algorithm as being at high risk for osteoporosis and potential fracture can increase their bone-mineral density with simple preventive measures. He’s also interested in conducting a similar study among younger people with no obvious clinical symptoms of bone weakening.

Photo by Joel Penner