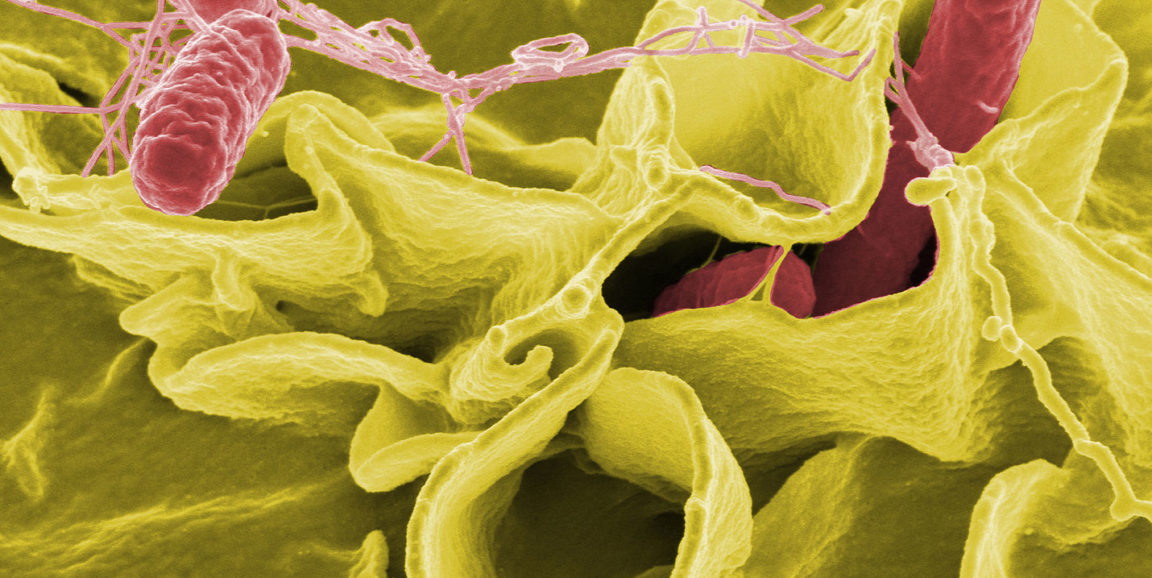

People respond differently when exposed to toxic bacteria: Some get sick and spread the infection, while others may remain unaware that they were contaminated. Illness from a common intestinal pathogen like Salmonella usually resolves within four to seven days, but infection can sometimes lead to hospitalization or death.

“It has been a real mystery to understand why we see these differences among people,” said Denise Monack, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology.

She thinks that new research, which discovered that a gut bacteria byproduct called propionate is protective against Salmonella in mice, may help clarify why responses differ so greatly.

The research appears in Cell Host and Microbe.

The scientists used mouse strains known to respond differently to Salmonella to determine whether their natural gut bacteria might be contributing to varying responses. From our press release:

'The gut microbiota is an incredibly complex ecosystem. Trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi form complex interactions with the host and each other in a densely packed, heterogeneous environment,' said Amanda Jacobson, the paper’s lead author and a graduate student in microbiology and immunology. 'Because of this, it is very difficult to identify the unique molecules from specific bacteria in the gut that are responsible for specific characteristics like resistance to pathogens.'

The researchers first wiped out the normal gut bacteria in both mouse strains with antibiotics. Then they implanted fecal matter from other mice, some that were resistant to Salmonella and some that were not. The results confirmed that the gut bacteria from one mouse strain was protective against Salmonella infection.

A specific group of bacteria, the Bacteroides, was more abundant in the mice showing resistance to Salmonella. Subsequent experiments revealed that a metabolic byproduct of Bacteroides, a short-chain fatty acid called propionate, was responsible increased the intercellular acidity of Salmonella, preventing it from multiplying and growing.

Again, from the release:

'The next steps will include determining the basic biology of the small molecule propionate and how it works on a molecular level,' Jacobson said. In addition, the researchers will work to identify additional molecules made by intestinal microbes that impact the ability of bacterial pathogens like Salmonella to infect and 'bloom' in the gut. They are also trying to determine how various diets affect the ability of these bacterial pathogens to infect and grow in the gut and then shed into the environment.

'These findings will have a big impact on controlling disease transmission,' Monack said.

The findings could also be useful in creating new treatments for intestinal infections that don’t involve antibiotics, which can make infections worse by also killing off the “good” gut bacteria.

Credit by Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH