Changes in the proportions of a type of white blood cell can predict when a tuberculosis infection will go from asymptomatic to active, according to a study led by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

A paper describing the work appears in Nature.

TB is a bacterial infection that primarily affects the lungs and is one of the top 10 causes of deaths worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About a quarter of all humans worldwide have latent TB, meaning the infection causes no symptoms and is not contagious.

Researchers led by Yueh-hsiu Chien, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology; Purvesh Khatri, PhD, associate professor of medicine and of biomedical data science; and Roshni Roy Chowdhury, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in microbiology and immunology, wanted to know how natural defenses keep the infection in check during latent TB. They also were interested to learn how the immune system changes when latent TB progresses to active TB infection, and what happens during treatment.

They looked at blood samples or gene expression data from people uninfected by TB or in different stages of infection: latent, active and post-treatment. They also compared immune data to TB-related lung pathology seen in PET scans.

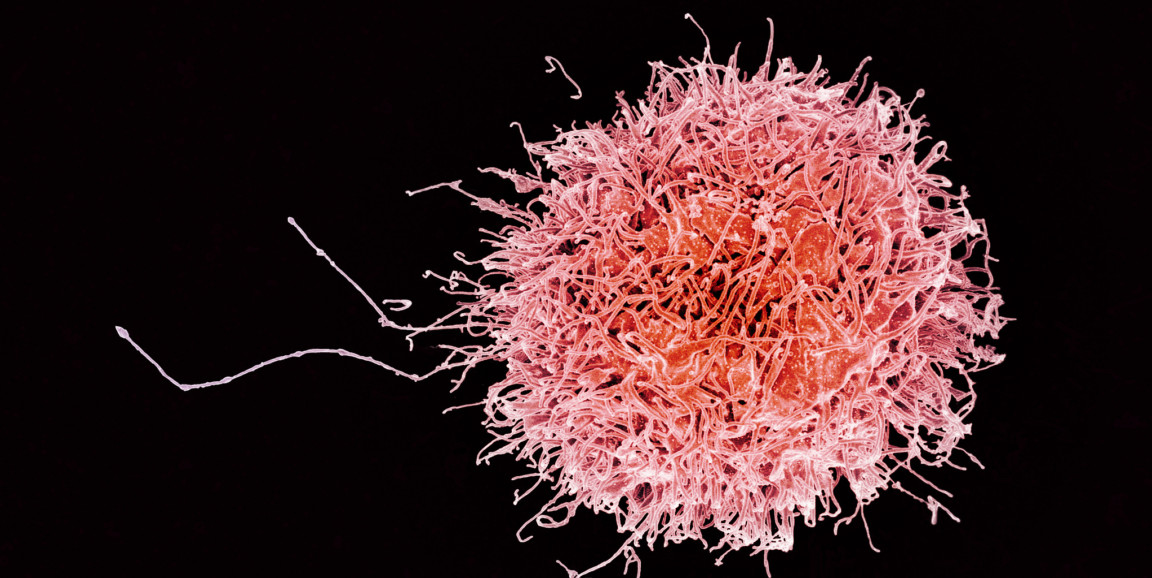

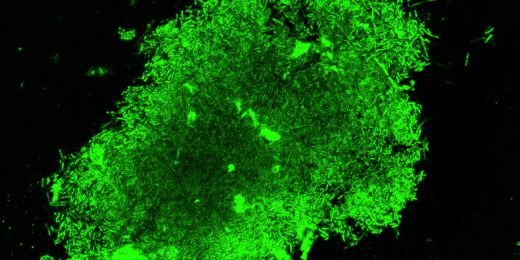

They found that higher proportions of a kind of white blood cell — called a natural killer cell, which is shown in the photo above — were present in latent TB. By looking at the change in proportions of these cells, the researchers could predict who was going to progress from latent to active TB. Higher numbers of circulating natural killer cells were correlated with less lung inflammation, but whether these cells are responsible for controlling TB infection or whether their proportions change to reflect TB activity in the lungs remains unknown.

The unexpected findings should help inform the development of vaccines and treatments for TB, the researchers say.

Photo by NIAID