About 30 years ago, Stanford’s Gerald Reaven, MD, often referred to as the "father of insulin resistance," hypothesized that the inability of the body to process insulin normally led to Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. He also thought that certain medical conditions that increase the risk for heart disease, such as high triglycerides, high blood pressure, and elevated blood sugar, were caused by an inability of insulin to do its job, or insulin resistance. He referred to this condition as Syndrome X, which came to be known as metabolic syndrome.

"It was a paradigm shift in the field," says Vivek Bhalla, MD, a Stanford nephrologist who was in high school at the time but would, by the time he entered medical school, become immersed in Reaven's theories himself. “Reaven’s theories started decades of ongoing investigations as to what role insulin played in a variety of diseases and organs.”

Kidneys — which, as a reminder, remove waste, help regulate blood pressure, in part by controlling sodium levels in the blood, balance fluids and direct the production of red blood cells — were not directly affected by insulin resistance, Reaven believed.

"Reaven's theory was that the kidney was somewhat of an innocent bystander in all of this," Bhalla says. "This was a natural thing for me, as a nephrologist, to work on." When he was offered a job at Stanford in 2008, Bhalla set out to learn more about the relationship between insulin resistance and kidney function, an effort that turned into a 10-year-long study.

What Bhalla and his team discovered is more complicated than what Reaven and other early researchers thought. Using mouse models of insulin resistance, their work showed that kidneys continue to process glucose normally, but their regulation of sodium is affected.

The study appears in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.

They found that, surprisingly, the kidneys continue to respond to insulin cues to process glucose, even as other cells and organs stop heeding the call to gobble glucose. But, on the other hand, the same kidney was less responsive, and therefore partially resistant, to insulin's signal that the organ should absorb sodium, lowering its levels in the blood. (Missteps in sodium regulation can lead to high blood pressure.)

"When cells respond to insulin, there are multiple different signals or pathways that insulin activates," explains Jonathan Nizar, MD, lead author of the study and an instructor at Stanford. “Even within one organ, like the kidney, it’s possible that one of those pathways, like the one that regulates glucose, could be working while at the same time, another pathway, the one that regulates sodium, is resistant or broken.”

Overall, these results contribute to a better understanding of insulin sensitivity in the kidneys and could, in the future, have implications for management of hypertension, hyperglycemia, and kidney disease, Bhalla says.

Bhalla got the chance to discuss the results of the study with Reaven before Reaven's death in February at age 90.

"I met him at a party about a year ago, and finally told him what I was working on," Bhalla says. "He said to please send him the paper, and we'd talk."

When the two met in Reaven's office, Bhalla admits he was a bit nervous, after all he was challenging a theory of the "father of insulin resistance." But it went well. "He said that he was quite pleased with our research. It was quite important to me to get his approval."

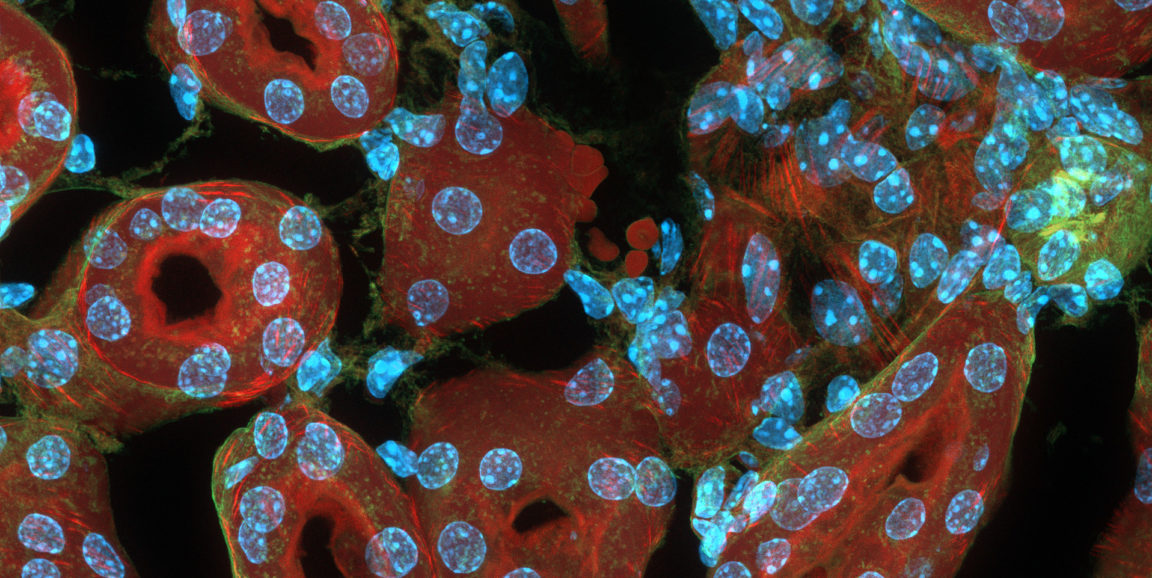

Photo of a cross section of a mouse kidney by ZEISS Microscopy