Cancer is indeed the emperor of all maladies. I learned that in the most excruciating way, losing two sisters and our mother to the dreadful disease. Through their illnesses and deaths, I learned how intractable and maddening cancer is, for the patients, their families, and for the health care team who bravely face each day trying to push back the tide of death.

I also learned what raw courage and love look like in 1989, when my then 33-year-old sister Maria prepared her two young children for her death, and their new life with me, the youngest of six Genovese sisters and the most unlikely candidate for motherhood.

Maria and I were opposites. In a look-alike family of eight kids, we were contrasts. Her fair skin burned the reddish tinge of the Maryland crabs she loved. I tanned dark, like my temper. Maria spoke like Julie Andrews in "The Sound of Music." I cussed like a dockworker. Maria's red gold hair was long and straight and smelled like Prell. Mine was short and black and smelled like dirt. Maria wanted to be a television broadcaster. I wanted to play wide receiver for the Washington Redskins.

We admired each other's strengths. I helped Maria learn how to swim and become a lifeguard. She tried to feminize my tomboy ways. I taught her how to climb out the bedroom window onto the roof to meet her wrestler boyfriend. She coached me through my first post-college job interview, saying, "Be yourself, but not too much."

When she was dying, Maria said, only half-joking, that she knew with me that her children would never be picked last for a team. Despite accomplishing so much in her young life, Maria had never forgotten the humiliation of standing on St. Jude's playground, waiting to be chosen for a team. There wasn't much she could control now that cancer had chomped holes in her liver and spine, but at least she could spare her children that potential suffering.

It's taken me decades to realize that Maria understood something about me then that I didn't understand myself. She knew that playing sports had helped me walk out of our less-than-ideal childhood into the world with clueless courage and a naïve belief that I could meet whatever challenge came my way. Sports taught me about winning and losing. About working hard for what I wanted. That on any given day, the underdog could win. She wanted her children, Sean and Kristen, to know those things too.

Often people ask me if it was hard to say yes to my sister. I answer no, it wasn't, but not because I was a good person or knew what I was doing. Quite the opposite. At 25, I was headstrong and obnoxious and the vastness of what I didn't know could fill the Grand Canyon.

But, at 25, there were two things I did know.

First, in so many ways, Maria had saved me. From our violent father, from making bad choices that would limit my life options, and from my own arrogant stupidity. I couldn't save her from this hideous disease, but I could at least offer her some small comfort knowing her kids would be loved.

Second, I knew that whether in a classroom, on the playing field or on the job, I was never the smartest, the most talented, the most anything. Except the most me: a girl so well loved by her Mom and sisters, that despite ample evidence to the contrary, she thought she could do anything. Including raising two toddlers who had just lost their Mom.

I realize now my love for my sister and my cocky ignorance were like a vaccine against fear and uncertainty. On that July day in 1989, I didn't realize the coming years would crash on me like a tidal wave, knocking me down, pinning me to the sandy, gritty bottom of life. So I took Sean and Kristen's hands in mine and walked confidently into a new life, and into a new way of being family.

Jacqueline Genovese is the executive director of the Stanford Medicine Program in Medical Humanities and the Arts (Medicine & the Muse)

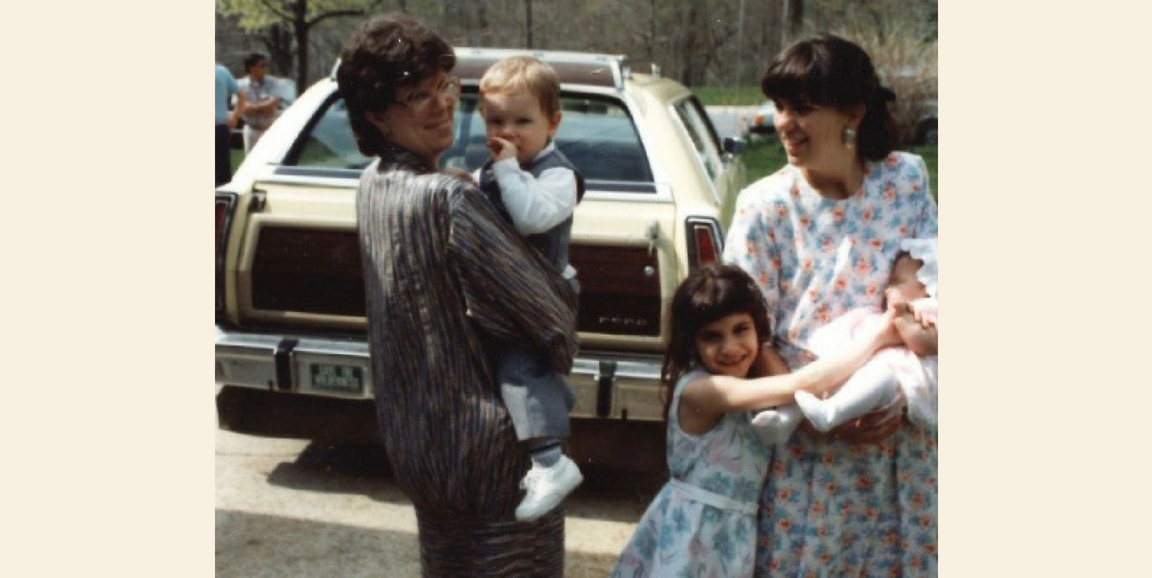

Photo, from left of Maria, Sean, niece Petra, Jacqueline and baby Kristen, courtesy of Jacqueline Genovese