The irregular heartbeat of atrial fibrillation (or AFib) is like dancing without rhythm, moving fast without a beat and stepping on your partner’s toes. If not treated, AFib is serious. It can reduce quality of life and, most ominously, can lead to a stroke. A stroke can kill off many millions of brain cells, paralyze parts of the body, interfere with speaking, or even cause death.

However, the nearly 6 million people in the U.S. who have AFib can take steps to reduce their risk of stroke. This blog series presents information, skills and health habits needed to lead a vigorous, fulfilling life with AFib.

First, let's meet George H., a 71-year-old retired engineer with high blood pressure. George frequently experienced episodes of a rapid, irregular heartbeat lasting up to an hour. Initially occurring monthly, over time the rapid fluttering in his chest became more frequent. Often, these episodes occurred in combination with lack of sleep, increased stress, or after drinking a few beers.

During one particularly frightening episode, George phoned his doctor who instructed him to come immediately to her office. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed AFib with an irregular heartbeat of 150 times per minute, a potentially serious situation. His doctor sent George to the emergency room for further evaluation. He left with two new prescriptions, but was disappointed by the lack of information he received.

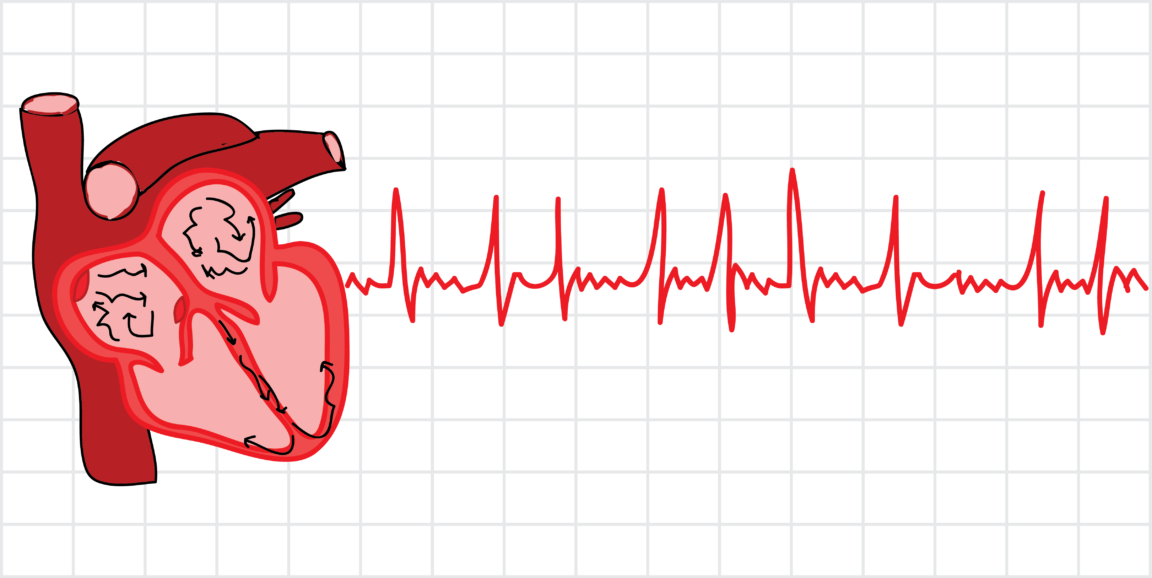

To better understand AFib, let’s review the mechanics of how the heart works.

An internal electrical impulse travels within the heart, which triggers the muscle cells, and the muscles to contract. Normally, the electrical signal first runs through the heart’s upper chambers (the atria) and then, moments later, through the larger, more muscular lower chambers (the ventricles). The squeezing power of the lower chambers pushes blood out of the heart.

A pulsation of blood travels like a wave through the arteries to reach everywhere in the body. This creates the usual rhythmic sound we associate with a heartbeat: lub-dub, lub-dub, lub-dub.

In AFib, abnormal, random electrical impulses in the upper chambers cause the atria to quiver (or fibrillate) rather than squeeze in a normal, coordinated way. Only some electrical signals in the upper chambers are allowed to trigger the muscles of the ventricles, thanks to the heart’s own safety system. As a result, the ventricles squeeze irregularly, usually 2-3 times a second in untreated atrial fibrillation (120-180 heartbeats per minute). In contrast, normal is 60-100 beats per minute.

What results is a dancing, irregular rhythm that is more like the fast gallop of a lame horse: dub-lu-dub-lu-lu-dub-lu-dub-lu-lu-lu-dub-lu-dub-lu-dub. With this rapid, syncopated rhythm, the heart can’t pump blood as strongly as it should. It can’t fill fully with blood and has too little time to rest between beats. As a result, people with atrial fibrillation often cannot exert themselves. Enjoyable physical activity is limited, a real problem given the health benefits of exercise.

A stroke can result when the quivering in the upper chambers allows small blood clots to form on the inside walls of the heart. These tiny clots can ultimately lodge in the brain, killing the part of the brain robbed of oxygen and nutrients.

Treatment of AFib can prolong life and promote greater well-being. Overall treatment goals include:

1) preventing blood clots and strokes through the use of blood thinners (anticoagulants)

2) slowing down the irregular beating of the heart to allow better heart function

3) and, for some patients, resetting the heart’s rhythm to a normal flow of electrical signals.

AFib, along with its underlying causes and recommended treatments, can be overwhelming. Learning to live with AFib, however, is worth the effort.

This is the first in a series of blog posts called Understanding AFib to help patients with atrial fibrillation live healthier lives. The next blog post will discuss which patients with AFib should consider taking blood thinners. George H. is an actual patient with some details altered to protect his confidentiality.

Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, is a professor of medicine at Stanford and practices primary care internal medicine. Stafford and Stanford cardiologist Paul Wang, MD, lead an American Heart Association effort to improve stroke prevention decision-making in atrial fibrillation.

Illustration by Vinita Bharat/Fuzzy Synapse