As a parent, I chuckled a bit when I first heard the term 'mitotic catastrophe.' The phrase describes a situation in which cells attempting to divide bungle the complicated maneuver and die an ignominious death. Even cells, it seems, sometimes find that the attempt to create happy, functional offspring is fraught with peril.

But, joking aside, the death of dividing cells — aka mitotic catastrophe — can have serious consequences, particularly when those cells, namely stem cells, are responsible for regenerating new muscle in response to injury or aging.

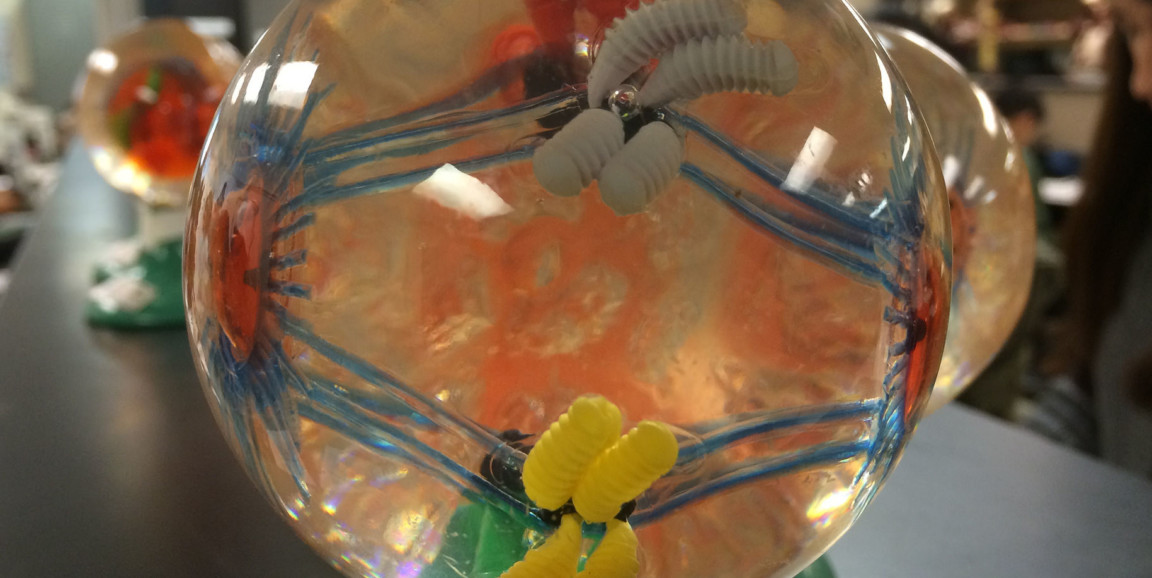

Now neurologist Thomas Rando, MD, PhD, together with senior research scientist Ling Liu, PhD, and pathologist Gregory Charville, MD, PhD, have pinpointed mitotic catastrophe as a cause of death of old muscle stem cells. These cells are less able than their younger counterparts to repair muscle damage. They've also shown that this "death by dividing" is the result of a malfunction of the cross-talk that occurs between the stem cells, nestled along the lengths of muscle fibers, and their neighboring cellular support team known as the stem cell niche.

They recently published their work in Cell Stem Cell.

As Rando explained in an email to me:

Mitotic catastrophe has primarily been described in the scientific literature as a way that cancer cells die, especially after treatment with chemotherapeutic agents. So it was a surprise to us to see the old muscle stem cells dying in this way. In fact, prior to this research, I had not even heard the term mitotic catastrophe.

In contrast, younger muscle stem cells usually divide without issue when called upon to do so, the researchers found.

Further investigation revealed that the catastrophic death of the aged muscle stem cells is related to a reduction in the amount of a protein called p53 in the cells. p53 is a well-known tumor suppressor that normally works to pause the division of cells with DNA damage to allow them the necessary repair time. When p53 is mutated, damaged cells continue dividing and sometimes become cancerous.

The researchers went on to discover that the decline in p53 is due to a reduction in the activity of a biochemical signaling cascade called the Notch pathway, which is activated in the stem cells by signals produced by neighboring cells. This close relationship between the stem cells and their niche has been shown by Rando and others to be vital in maintaining the function of stem cells.

As Rando explained:

Increasing evidence points to the cross-talk between stem cells and their niches as being essential to maintain normal tissue homeostasis and repair. If one disrupts the stem cells or the niche cells, these processes are impaired.

Some stem cells persist in a quiescent state for years or even decades, and normal structure and function of the stem cell-niche unit appears to be essential for such long-term cell, tissue, and even organismal survival.

Because DNA damage accumulates with age, Liu, Charville and Rando wondered whether it was possible to avert mitotic catastrophe in the aged stem cells by treating them with a drug that increases p53 expression — perhaps by giving them breathing room to repair the damage before dividing. Indeed, they found that boosting p53 expression in the stem cells allowed them to divide more successfully improved their ability to repair muscle damage.

Rando and his colleagues are now keen to learn whether intervening in this natural aging process of the stem cells and their niche can lead to therapies that can help old muscles, and potentially other tissues and organs, heal more quickly and efficiently.

As Rando said:

We want to know why Notch signaling declines in the muscle stem cell compartment with age. This could suggest another potential therapeutic approach to preventing mitotic catastrophe in aged muscle injury. And we would like to know whether these findings represent a general phenomenon in aged stem cell populations.

Photo by ChangGp