On a sunny Saturday afternoon in September, I navigated through an unfamiliar section of east San Jose, en route to Andrew P. Hill High School, the home of a science exploration program created by a group of Stanford science graduate students in 2015.

The program, known as FAST (Future Advancers of Science and Technology) is now in its fourth session and has over 100 high school students currently participating. It's also growing: This fall it expanded to include a second San Jose high school. But it has no employees -- the logistics, curriculum and fundraising are all led by a team of Stanford science graduate students who volunteer their time.

Patrick Allamandola, the Andrew Hill science teacher who partnered with Stanford graduate students to launch FAST, describes the area I am weaving through as a section of San Jose bounded by four highways: 101, 87, 280 and 85. For many of the high school students, especially those who lack cars, those roads are the limits of their neighborhood, their worldview, he said.

Take Ezequiel Ponce, an Andrew Hill senior and veteran FAST participant. Ponce's mother wasn't able to finish high school. Nonetheless, she and Ponce's father told their son that he needed to go to college.

Like many students, Ponce initially enrolled in FAST to help with an International Baccalaureate science class assignment and, also like so many students I talked to, he initially found FAST intimidating.

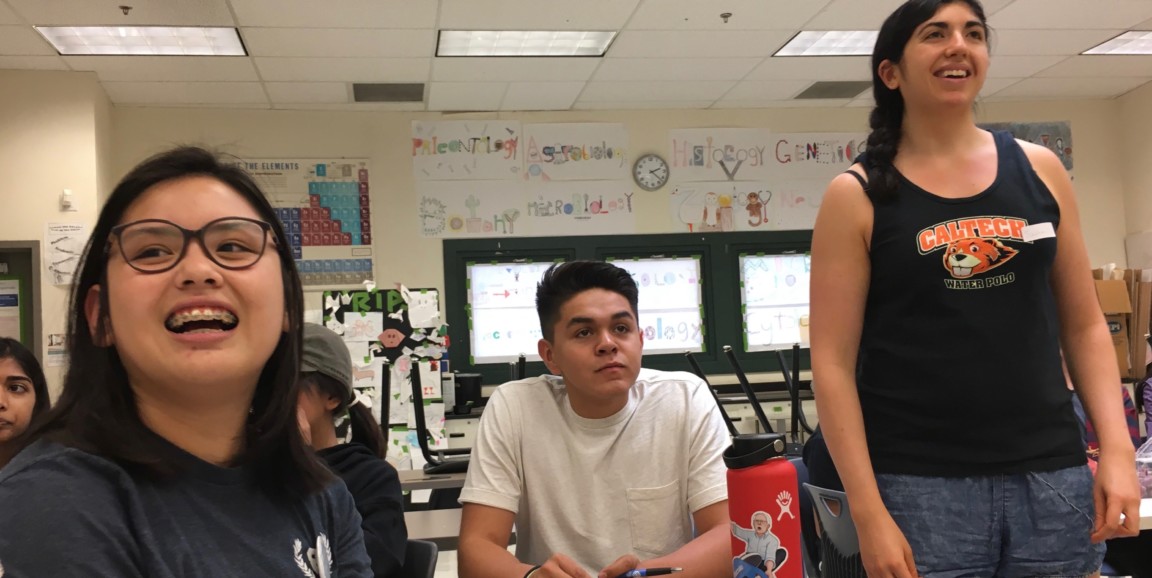

"But as I went to more and more meetings, it became more fun than like school work to me," Ponce said.

Andrew Hill senior and third-year FAST participant Angelynn Nguyen had a similar take: "It didn't seem like the science they teach in school. We were able to research about any part of science we liked and for me that was microbiology. It wasn't stressful, it was fun."

I had asked the students I had previously reached out to what kept them coming back week after week, devoting nearly a quarter of many of their weekends to the program.

"FAST quickly became a second home," explained Thao Pham in an email. Pham graduated from Andrew Hill this spring after two years in FAST. She isn't close with her family and had always assumed that science was too hard for her. "FAST was more than a program that helped me recognize my passion for science, it was a place of growth... I'm so glad and grateful for the person I've become because of this program."

Now, Pham is beginning her first year at the University of California, Los Angeles, planning to double major in civil engineering and business economics.

After hearing testimonials like that, I was anxious to see FAST in session for myself. Eventually, I found the parking lot that Alex Dunlap, a Stanford graduate student in mathematics and FAST chief program officer at Andrew Hill, had described to me.

I opened the door to the two-story building I was guessing was the science headquarters and seeing no one, made my way up the stairs and into one of the classrooms.

There, Katie Liu, a Stanford graduate student in chemistry and chief operations officer of FAST, stood before a room of high school students, laying out a step-by-step process for applying to college.

As FAST matured, its leaders realized that in addition to working on their independent science projects, the Andrew Hill students had other needs that they could meet. They inserted one-hour workshops into the biweekly schedule, tackling topics such as applying to college, financial aid, ethics, coding and tips for feeling comfortable in an academic community, FAST development officer Erin McCaffrey, a Stanford graduate student in immunology, described.

The guidance, Andrew Hill students told me, is welcome.

"First-generation parents are motivating their kids to go to college, but we don't really know how to get there," Ponce said. "Before FAST I didn't know what I was doing... Now I have a plan. They are helping with all of that."

On this Saturday, the students assembled in rooms grouped by their interests.

In past years, student projects have delved into food chemistry, microbiology, sustainable energy, plant biology and molecular biology, among others, McCaffrey told me. This year, FAST is adding mentors skilled in public health, she explained.

I tagged along to watch the brainstorming process in action.

Led by Sasha Zemsky, a Stanford graduate student in biophysics, the students were jotting down ideas on slips of paper. Zemsky gathered them together and then read them, without names, one at a time:

- How can we help people who have had a stroke?

- What are the antimicrobial properties of honey?

- What enzymes are in food?

- Does temperature affect bone health?

- Do any animals reproduce like spiders?

Using school computers, the high schoolers were given a few minutes to look up existing studies addressing the questions. Later sessions would match the students up with their mentors, and then shape and dive into the projects themselves.

In the spring, the FAST students have the opportunity to enter their projects in regional science fairs, with the potential to move on to the state fair, and present their work at a symposium at Stanford.

"You can really tangibly see these outcomes that are positive," McCaffrey said. "The students blossom from feeling insecure about their idea to becoming miniature experts in their field."

I whispered goodbyes and returned to my car, leaving the students beginning, exploring, embarking.

This is the second installment of a four-part series on FAST.

Photo of, from left, Angelynn Nguyen, Ezequiel Ponce and Sasha Zemsky by Becky Bach