Picture an extra-lengthy, extra-thin, extra-flexible slab of greasy cheese coiling itself in multiple layers around a foot-long hot dog.

Not quite the picture one usually has in mind when thinking about how our brains work, is it? But a set of fat-filled brain cells called oligodendrocytes are critical to pretty much everything the brain does — as much so, really, as the nerve cells or neurons (the hot dogs in my metaphor), that oligodendrocytes wrap their flabby protrusions around. (The cheese-like flab is a squishy substance called myelin.)

Many real-life neurons make their living by schlepping signals from one brain circuit to another distant one. These neurons need insulating coatings in order to faithfully transmit information, just as household electrical wires do. Oligodendrocytes supply that insulation by wrapping neurons within multiple layers of myelin-rich extensions, preserving signal strength and markedly speeding up transmission. (Bundles of myelinated neurons take on a whitish appearance and constitute the brain's so-called "white matter.")

For the brain's distributed operation centers to work in sync, it's crucial that just the right nerve cells — and only those nerve cells — get wrapped during early development and stay wrapped. Failure can spell outcomes such as cerebral palsy, the most common childhood disability.

So, how do you learn about myelination and what can go wrong with it? Studying oligodendrocytes — or for that matter any cells of any type — in the developing brain of a living fetus, is a non-starter. Nerve cells are somewhat amenable to scrutiny in laboratory cell culture, but, as I write in a news release:

[S]tudying human oligodendrocytes has been tough. They’re born late in brain development, and they’re challenging to generate alongside ... other brain cells in a way that recapitulates the complex interactions occurring among these cell types as they develop.

Now, in a new study in Nature Neuroscience, Stanford neuroscientist Sergiu Pasca, MD, has found a way to pry loose the secrets of oligodendrocyte development.

A few years ago, he and his colleagues figured out a revolutionary way to grow sustainable cultures of functioning human neurons in culture. The cells grew and multiplied to become almost perfectly round balls in suspension, each ball containing as many as 1 million cells and measuring as much as one-eighth of an inch in diameter. Remarkably, the spheroids spontaneously developed as concentric layers of cells resembling the layers of the cortex of the human brain. Plus, they contained another absolutely key brain-cell type known as astrocytes. (I've told this tale in full detail in "Brain Balls," an article I wrote in 2018 for our magazine, Stanford Medicine.)

There’s as yet no sign of a time limit to how long Pasca’s spheroid cultures can persist — so far, viable brain spheroids have been surviving in culture for at least two years.

“In principle, they can go indefinitely,” Pasca told me. In the new study, he and his team succeeded in tweaking brain spheroids until, eventually, they spawned functioning oligodendrocytes capable of positioning themselves next to neurons and myelinating them.

Being able to monitor these interactions in a laboratory dish may make for great strides in the understanding and treatment of cerebral palsy and, perhaps, other myelination disorders such as multiple sclerosis.

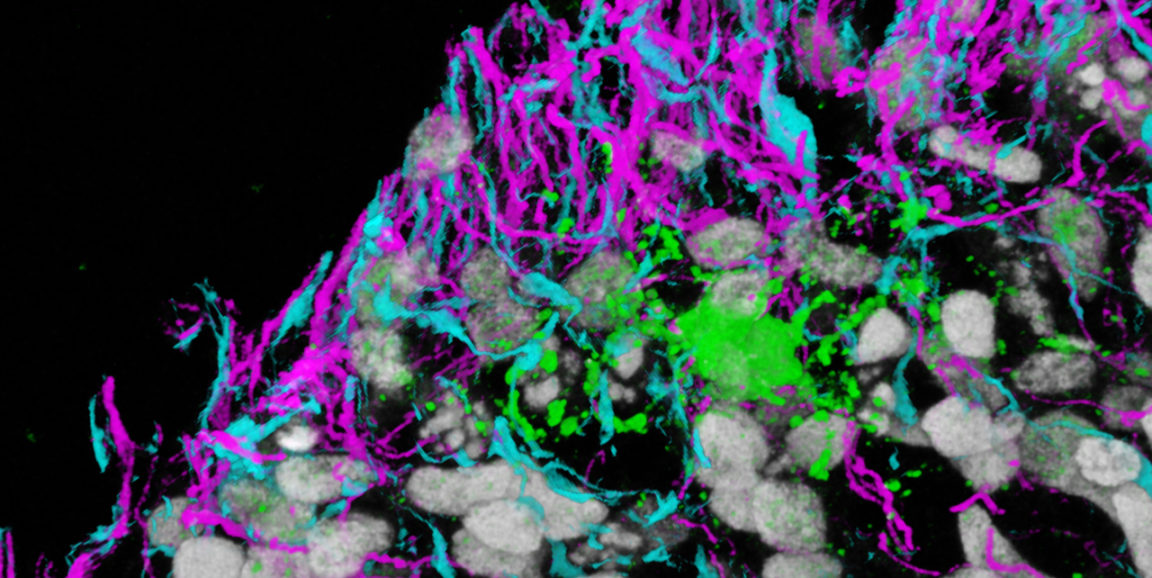

Photo of three different brain-cell types in a dish courtesy of the Pasca lab. Neurons are magenta; astrocytes, blue; and oligodendrocytes, green.