Before Constance Chu, MD, enrolled in medical school, she spent five years in the military as an intelligence officer, commanding an imaging unit. "We were trying to uncover hidden things," said Chu, now a professor of orthopaedic surgery at Stanford.

She continues trying to uncover hidden things, but now her target is cartilage damage in injured knees.

"I'm still doing the same thing," she said, "trying to make risk assessments using imaging. I'm using many of the same thought processes that I learned as an intelligence officer."

As a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, Chu and two colleagues developed a new type of MRI that can reveal damage to knee cartilage as soon as a year after an injury. The technique, UTE-T2*, generates a color map of the cartilage deep beneath the surface.

"We now have the makings of an early warning system," Chu said.

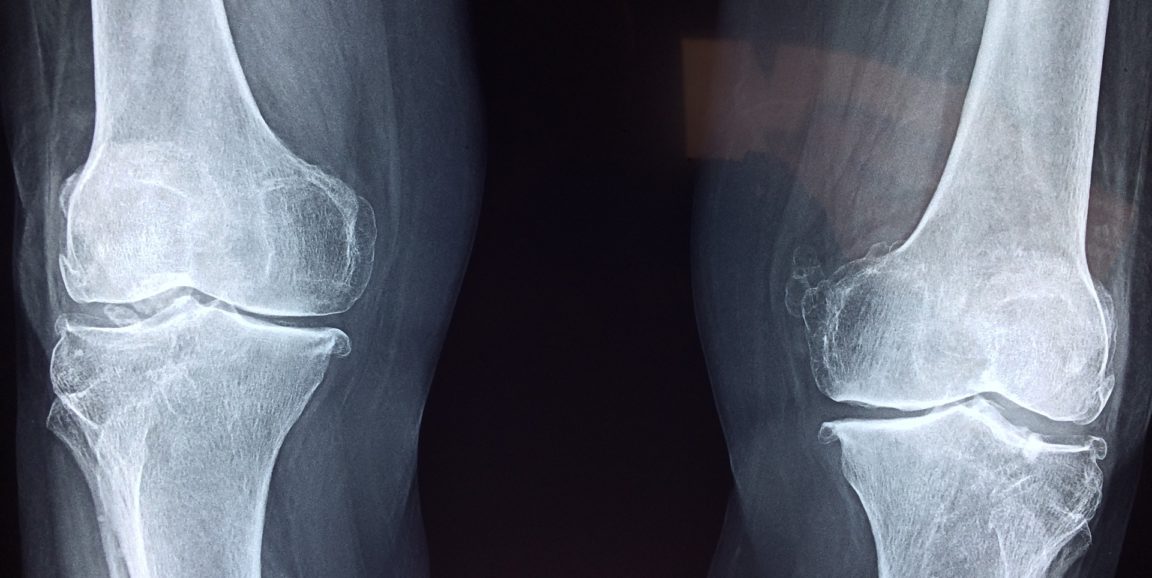

Before UTE-T2* was available, clinicians were unable to diagnose cartilage damage until 10 or 15 years after an ACL injury, when about half of patients will have developed osteoarthritis. At that point -- when the patient is limping in pain and it's too late to effectively treat the problem without a knee replacement -- an X-ray or regular MRI will show that the cartilage has worn away.

But now that researchers can diagnose pre-osteoarthritis, they can seek treatments to prevent osteoarthritis from developing.

Chu and her lab team at Stanford recently won the department's largest-ever research grant to support their work. They are running five studies, including two clinical trials, to test prevention strategies. In one trial, her research team will look at how patients walk after they are injured and whether improving their gait can prevent the condition from developing.

In another, they will test gene therapy in horses, who develop osteoarthritis similar to the way people do. The researchers will also study some possible preventive medications that have already been approved by the FDA, as well as stem cell therapies: "We want to see if the young and healthy cells can improve recovery from joint injuries," she said.

Finally, they are conducting some basic science research. They're looking at the molecular changes during deterioration of the cartilage, in the hopes that they can improve understanding about how injuries lead to osteoarthritis.

"We're on a path toward preventing and finding a cure for pre-osteoarthritis and reducing the number of people who are disabled from joint pain and who need metal and plastic replacements," Chu said. "That's the most meaningful to me and my team -- to make a difference for patients."

Image by Taokinesis