Suicide is deeply personal -- shattering individuals and families. And a host of individual factors -- such as depression and alienation -- increase the risk of suicidal behavior.

However, suicide rates are affected by a variety of broader societal and economic factors, opening opportunities for public health interventions, speakers Anne Case, PhD, a Princeton economist, and Rebecca Bernert, PhD, a Stanford suicidologist, said at a recent Stanford Health Policy Forum moderated by Paul Costello, senior communications strategist and advisor.

Case and Bernert approach suicide from different angles -- Bernert, from clinical psychology and Case, from economics.

And for Case, suicide includes what she and her colleague and husband Angus Deaton, PhD, have coined "deaths of despair" -- those resulting from alcohol, drugs or intentional self-harm. "There's no bright line, you're killing yourself slowly or quickly," she said.

Case and Deaton are known for their discovery that death rates are rising for the middle-aged white working class in the United States, spurred by upticks in suicide, drug and alcohol overdoses and chronic liver disease.

"I think a lot has to do with the fact that hope disappeared, community disappeared," Case said.

Economic distress alone can't explain the phenomenon, however, the researchers said. After all, Bernert pointed out, in times of widespread economic downturn, or national crisis such as 9/11, suicide rates don't climb.

"It's thought to be a coming together when times are difficult," she said.

Yet for white Americans without a college degree, the sustained pressure is too much, Case believes. Globalization and the loss of higher paying blue-collar jobs plays a role, she said, but that doesn't provide a full explanation, in part because it is a uniquely American problem.

Jobs have disappeared in Europe as well. What stands apart in the United States is the opioid epidemic, the lack of a social safety net and the trait of American individualism -- together they have fractured communities. The thought is "I take care of me and my family, you take care of you and your family," Case said. "But when things go south, you don't have a lot of support."

In response to Costello's question about what policy changes would make a difference, Case and Bernert agreed there are many.

First, expanding access and reforming health care, including addiction treatments, they said. "We need a real push to treat [the opioid epidemic] as the emergency it is," Case said.

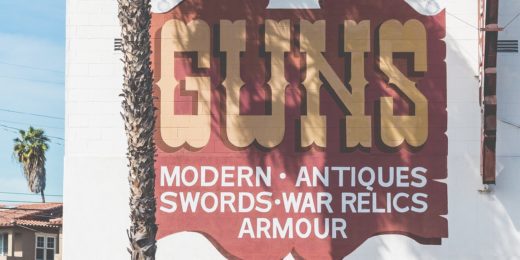

For Bernert, amping up suicide prevention efforts is a no-brainer: After all, suicide deaths are preventable, she emphasized. Policies could help break down harmful myths (such as the oft-repeated belief that most people who die by suicide leave a note) and bust the stigma that often impedes discussion and progress. They could also restrict access to "lethal means" -- as does the new Golden Gate bridge barrier.

"If you put time and space between the thought and the means, you prevent loss of life," Bernert said. People who are stopped from attempting suicide are, in most cases, saved, she said.

"Every problem in suicide prevention, I would argue, should be viewed as a critical opportunity for change," Bernert said. Think gun locks or systems to limit access to pills.

And then, an even broader question from an audience member: "How do we start healing society?"

Build community, Case suggested. Cultivate hope as well, Bernert added.

"There's a tremendous need to raise awareness that suicide is preventable and that these very effective interventions exist," Bernert said. "We need to find ways to bring that hope and treatment to the masses... especially those in need."

Individuals in crisis can receive help from the Santa Clara County Suicide & Crisis Hotline at (855) 278-4204. Help is also available from anywhere in the United States via Crisis Text Line (text HOME to 741741) or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255. All three services are free, confidential and available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Photo by Becky Bach