A pattern of inflammatory activity in circulating blood cells two days after a stroke predicts the likelihood of losing substantial mental acuity one year later, according to a study published in Brain.

Knowing, early on, who's at high risk for delayed cognitive losses from a stroke is an important step toward figuring out what immediate post-stroke treatments might best prevent those later losses -- which occur with distressing frequency, as I noted in a news release about the study:

In developed countries such as the United States, 3 out of 4 stroke patients survive for substantial periods of time. However, these survivors are at twice the normal risk for dementia over the next decade, even if their cognition was initially unimpaired by the stroke.

The study, conducted at Stanford, was led by neurologist Marion Buckwalter, MD, PhD; immunologist Brice Gaudilliere, MD, PhD; and statistical innovator Nima Aghaeepour, PhD. The three scientists and their colleagues drew blood at numerous time points from consenting patients who'd arrived at Stanford Hospital within 24 hours of experiencing a stroke.

Soon after each blood draw, samples were analyzed via mass cytometry, a technology pioneered at Stanford over the last decade. Like an ultra-high-performance barcode reader, mass cytometry provides a rapid-fire cell-by-cell assessment of numerous properties and activation states of the 10 million or so individual immune cells obtained in a simple blood draw. The researchers were able to distinguish among all the important immune cell types in each sample, as well as to count the numbers of cells of each type and to determine each cell's activation status (whether the gene is quiescent or, alternatively, the extent to which its capacity to order a particular protein's production is being put to use).

The immune system's constituent cells are highly interactive, so their activities are often coordinated. "It's like a gaggle of teenagers looking at a new cut of jeans in a store window and deciding as a group that they've all got to have a pair," as Buckwalter puts it.

So each patient's mass cytometry results were fed into an algorithm, developed in Aghaeepour's laboratory, that was specifically designed for its ability to sift through huge, massively complicated collections of highly correlated data and find a manageable number of key connections.

Patients were also given, at multiple time points after their stroke, a mental-acuity test specifically designed to detect deficits in various aspects of cognition such as spatial knowledge, memory and ability to perform calculations. Their scores on this test were also fed into Aghaeepour's algorithm.

The investigators identified three distinct phases through which the immune system progresses before returning to normal about a year after the event. Each phase is marked by its own unique set of deviations in relative numbers and activation levels of a small number of immune cell types in the blood.

From our news release:

It was the first, or acute, phase, peaking just two days after the stroke, that grabbed the researchers' attention. The more exaggerated the deviations among the handful of immune cells identified as defining that phase, the more likely a participant was to suffer a drop in performance on the mental test between three months and one year out from the event, the study found.

If these results are confirmed in a similar, scaled-up study now underway, it could lead to targeted measures to forestall dementia by tweaking activity just in particular implicated immune cell types during the crucial first days following a stroke.

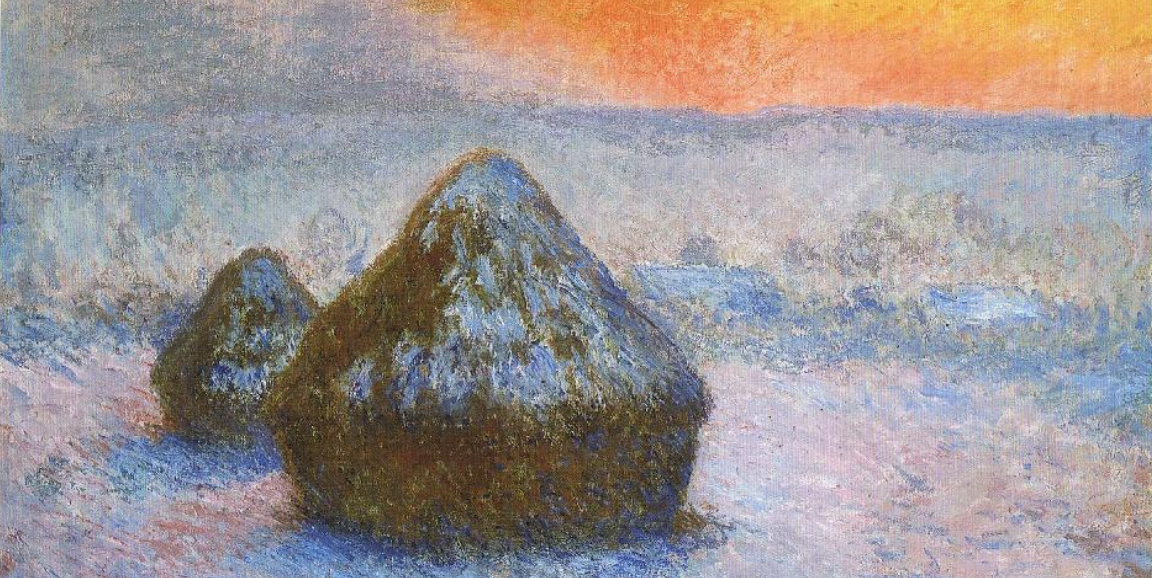

"Mass cytometry lets you measure the entire haystack in order to find the needle," Gaudilliere told me. "Once you have the needle, you don't need the haystack anymore. You can focus on just a few features of a few cell types."

Image of Claude Monet painting, Art Institute of Chicago