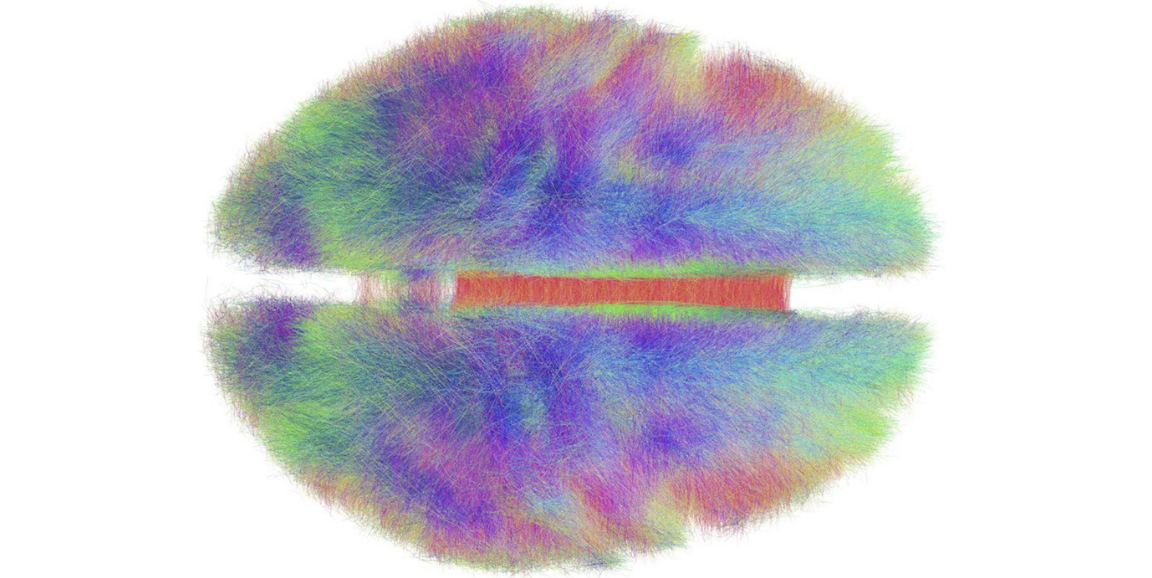

Concussions can vary in symptoms and severity but researchers often don't understand why. So, in an attempt to resolve a clear-cut relationship between physical trauma and concussion diagnosis, researchers at Stanford University choose to focus on one specific area of the brain — the corpus callosum, a thick bundle of nerves that joins the two halves of the brain and plays a role in coordination.

This structure, they suspect, may be the key to understanding concussions associated with symptoms of dizziness and vision problems.

"Concussion is a big, vague term and we need to start breaking it down," said Fidel Hernandez, PhD, a former graduate student in bioengineering, in a Stanford News press release. "One way we can do that is to study individual structures that would be likely to cause traditional concussion symptoms if they were injured."

Through a combination of biomechanical measurements of athletes-in-action, computer simulations, and medical imaging, they suggest that hits to the side of head — which cause the head to turn or tilt to the side — send vibrations through the brain that disproportionately affect a relatively stiff section of tissue, called the falx cerebri. The falx cerebri is connected to the corpus callosum, so movement of the falx cerebri could damage that structure. The paper with details of their work was published in Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology.

Their biomechanical data from mouthguards worn by football players recorded 115 impacts but only two were related to diagnosed concussion. The researchers examined the brains of the players diagnosed with concussion using MRIs and both showed signs of possible damage to the corpus callosum.

Although the scans, measurements and simulations told a cohesive story about the connection between side hits, the corpus callosum and concussion, the researchers stress this is still a hypothesis and requires more data, including additional information from subjects diagnosed with concussion. They also emphasized that this work doesn't suggest that concussions should be diagnosed using scans.

In the press release, Michael Zeineh, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiology and co-senior author of the paper, cautioned:

The bottom line is, when we do post-concussion brain scans in clinical settings, we don’t find anything. I’d say 95 percent of them are normal. Clinically, we interpret by eye, but the kinds of changes we’re showing in the paper, you can’t see with your eye. Concussion cannot be diagnosed by imaging alone.

But, by using all tools available to better understand the cause of specific concussion symptoms, we could help develop better treatments and preventative measures, said David Camarillo, PhD, assistant professor of bioengineering and co-senior author of the paper.

And perhaps the work will indicate that concussions aren't as concrete as we believe. “All concussions are not created equal,” said Hernandez. “We try to draw a line – a binary ‘yes concussion’ or ‘no’ – but concussions happen on a gradient.”

Image of structural and functional connectivity in the human brain by Andreashorn