It was almost like dancing. You stood and held out your arms crossed at the wrists. I did the same, linking hands with you. I walked backward and you forward.

We made slow, careful steps toward the bathroom.

"Look," we said, proud of ourselves.

We focused on the next step. The smooth lift. The careful bend.

At first, all you'd needed was a hand on your elbow. I made myself strong and steady like a tree. A week later, we dance-walked to the bathroom. Then, the bathroom was too far.

Soon, walking wasn't possible at all.

I placed the wheelchair at the correct angle. I reached around in a sort of reverse seatbelt, wrapping my hand as gently as possible around your back. We hugged, then. A quick kiss. You moved your legs toward the edge of the bed. Later, when you couldn't move them, I did that part.

Whatever your body needed from mine, I wanted to give.

Therapists came to our home to help. Occupational therapists. Physical therapists. Speech therapists.

"You might want to apply for a caregiver," the therapists said.

A man from the Department of Social and Health Services came to interview us.

"What kind of qualities are you looking for in a caregiver?" he said.

"Just someone competent," I said.

The very next day, the man from DSHS called.

"I found someone for you," he said. "He's very competent. His name is Dwayne. He'll be there tomorrow at 9 a.m."

I imagined the tall, strong man who would arrive in the morning. He'd come in, assess the situation, and act.

Dwayne showed up right on time. He was a foot shorter than the man I'd imagined, with a doughy, slouching frame. He smelled like cigarettes.

"Hi," he said. "I'm Dwayne. It's my first day."

I explained your condition, stage four brain cancer, also known as glioblastoma multiforme, as well as the meningitis you'd contracted after the most recent surgery.

"He still hallucinates," I explained. "He can't see very well. He has a hard time supporting his weight at all. Also, with the meningitis came incontinence... "

Dwayne interrupted. "What's incontinence?" he said.

I stared at him.

"I don't know what that word means," he said.

I didn't want to make him feel bad. "Oh, it means that you don't know you have to urinate so you can't control it. I'm sorry, how do you not know that word?"

"I told you this was my first day," he said.

"Ever?" I said. "What did you do before this?"

"I've worked in a grocery store for the past 27 years," he said.

Dwayne talked about what had drawn him to the caregiver role. He cared about people. He wanted to help. That was all fine, but, as I would explain to his supervisor, I needed someone whom I didn't have to teach.

The supervisor was sorry.

"Does he have any training at all?"

"He completed the five-hour basic training module, which is all that's required to get started," he explained.

One by one, I called the remaining agencies. The wait was long. Qualified candidates were few.

We were on our own.

My Love, I confess, it was too much for me to bear. Your weight, I could hold, 30, 40 times a day if necessary, but even that, I tried to minimize. Were you sure you needed to go to the bathroom? What about the previous six trips we'd made in the last hour, when you hadn't needed to go after all?

An edge crept into my voice and I hated myself for it. I didn't want to condescend. I couldn't seem to help it. I was so tired.

I watched your body fail you. Still, we were hopeful. Maybe you'd get better. I tried to encourage myself, though you had always done a much better job of it than I ever could.

On the first day I did not have to move your body, I lay next to you in bed and cried. From then, there would be no more lifting. No more hugs during transfers. No more of our dancing those steps we'd learned so very well.

I made my body like a chair to prop you up, to help you breathe, holding you, singing to you, whispering love. We were all there for you, with you. It was like waiting for someone to be born. In the end, you did it all by yourself.

This piece, originally in longer form, is part of an ongoing collaboration with Months to Years, a nonprofit publication that showcases nonfiction, poetry and art exploring mortality and terminal illness.

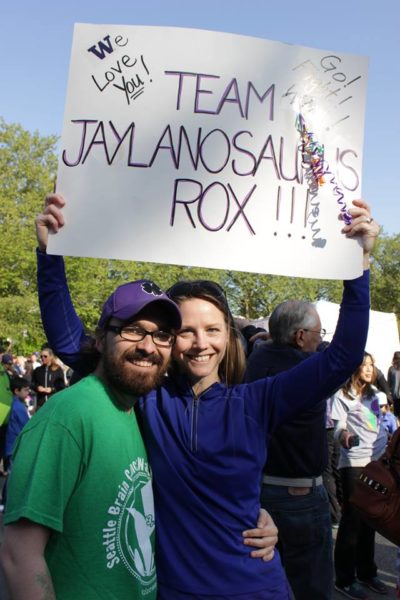

Nicole Hardina, a writer in Seattle, is the recipient of an Artist Trust grant for her memoir in progress, When I Spin Away. Her partner, Jaylan Renz, died in 2017 of brain cancer at the age of 33.

Photo by Simon Matzinger