Brothers Ronnie and Levi Dogan were born with IPEX syndrome, a life-threatening genetic disease that causes patients' immune systems to attack their own healthy tissues. A new story I wrote for Stanford Medicine magazine explains how an unusual stem cell transplant technique used at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford saved the lives of the boys, who are now 2 and 1.

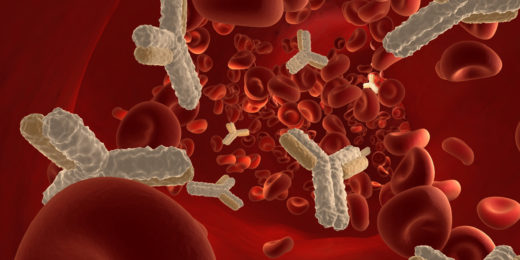

Stem cell transplants remove blood-forming stem cells from a healthy donor, and then inject them into a patient, where they take hold and grow in the bone marrow. The transplants were first developed for people with blood cancers, but have the potential to be used much more widely for a variety of genetic diseases. If given in tandem with solid-organ transplants, they could also remove the need for immune-suppressing therapy in organ recipients.

But traditional stem cell transplants are so risky that they've usually been offered only to patients who would otherwise die.

One potentially fatal complication, graft vs. host disease, occurs when the new, donated cells respond to the immune markers on a patient's own cells -- known as HLA antigens -- as if they are foreign, and mount an immune attack against the patient's body. Several Stanford teams are now working on research to make the transplants gentler and safer, which would broaden the circle of people who could be helped.

Ronnie and Levi benefited from one such advance. Before she came to Stanford, their doctor Alice Bertaina, MD, PhD, developed a technique that greatly reduces the risk of graft vs. host disease and broadens the potential pool of stem cell donors.

My story explains:

People inherit half their HLA antigens from each parent. An ideal transplant scenario is to use stem cells donated by a healthy sibling with a 10-for-10 antigen match. Ronnie and Levi didn't have other siblings. A second-best option is to find a match using a donor registry. But patients from ethnic minority populations are less likely than white patients to match to a registered donor, and none were a fit for Ronnie or Levi, who are black.

The technique Bertaina pioneered in Italy takes a different approach. Technicians process stem cells from the donor to eliminate alpha-beta T cells, immune cells that instigate graft-versus-host disease. As a result, patients can be safely transplanted using stem cells from a donor with only 5 of 10 matching HLA antigens -- such as a parent.

The processing method allowed Ronnie and Levi to receive a stem cell transplant from their father, who does not have the autoimmune disease. The procedure, which was not available at any other U.S. hospital when the brothers received it last year, is now offered to most transplant recipients at Packard Children's.

Bertaina's colleague Rosa Bacchetta, MD, is conducting research that goes further. She's developing gene therapy techniques for IPEX syndrome. Again, from the story:

'The main, huge difference is that with gene therapy we correct the patient's cells,' Bacchetta said. 'We will not have to face all the problems of compatibility between the donor and patient.'

Bacchetta and her team are pursuing two gene-therapy approaches, one of which is close to moving into clinical trials in people. They hope that their approaches will provide useful therapies not just for IPEX syndrome, which is extremely rare, but also for other, more common autoimmune diseases as well.

Photo of Levi, left, and Ronnie napping in the arms of their grandmother, Rosemary Anama, by Timothy Archibald