When cholera hit London in late 1854, experts thought the outbreak was caused by "miasma," or bad air -- a conclusion that suggested neither how to contain the disease nor cure it. John Snow, a pioneer of epidemiology, turned to a different tool: a map. Plotting deaths caused by the disease, Snow noticed the fatalities were clustered around a few of the city's wells, leading him to hypothesize the disease was carried by London's well water, not its air. Snow's insight would usher in the modern era of public health.

More than a century-and-a-half later, we're still plotting outcomes on maps to inform public health interventions. But instead of reacting to crises, we're now on the verge of using data -- from a growing number of source -- to predict and prevent them before they strike. This is the realm of precision population health, a new frontier that could improve the lives of millions of patients. To see this future, look no further than Louisville, Kentucky.

Air Louisville was "designed to be the largest public health study of respiratory disease ever conducted by a public-private collaboration." The 2018 study provided more than a thousand Louisville residents with smart inhalers to digitally monitor their asthma and pinpoint where and when they experienced symptoms. Using this data, combined with roughly 5-million data points on the local environment, from pollution to weather, researchers created sophisticated maps showing how daily changes in these variables affected people with respiratory disease throughout the city. These insights led to important breakthroughs.

For one, study participants saw a 78% reduction in rescue inhaler use, which was credited to improved health monitoring made possible by the smart inhalers. In addition, the Louisville Metro Government used data from the study to take a number of policy actions that will help residents breathe easier: increasing tree coverage in high-risk areas, re-routing commercial trucking routes, and considering new zoning laws to protect neighborhoods exposed to industrial emissions. It's an impressive and novel approach to addressing a complex public health issue that costs the U.S. $56 billion annually.

This is the promise of precision population health: using data to predict health issues and intervene before they become medical emergencies. It is a story that will only get better with time. We're generating and collecting more data every day; we're improving how we share and study it; our tools are becoming more powerful; and breakthroughs in one area are starting to inform and inspire breakthroughs in others. Health care providers, policy makers, and patients all stand to benefit.

Indeed, as the tools of population health continue to evolve and become more multidisciplinary, there is growing recognition among clinicians that they, too, will need to embrace a more holistic view of medical practice.

A study published in the Permanente Journal last year used U.S. Census data to predict whether a person's neighborhood increased their risk of developing Type 2 diabetes. The study found two markers in a neighborhood -- the area's socioeconomic status and amount of food assistance -- that predicted greater risk of an individual progressing to Type 2 diabetes.

More than ever, issues such as food access, housing security, environmental pollution, and other factors that influence a person's health are falling within the domain of clinical care. This presents the medical community, in particular, with a unique opportunity to collaborate on efforts that will not only advance the health of patients today but potentially entire generations to come.

Over the next few years, a study co-led by associate professors at San Francisco State University and Stanford Medicine, will examine "the health outcomes for individuals whose parents benefited from New Deal programs."

It's an intriguing question -- what lingering effects did a key piece of national economic legislation have on individual health? It's also a timely one, given the ongoing discussions in the U.S. about the future of health care and social safety net programs. Regardless of party or ideology, the study's findings, which will incorporate data spanning eight decades, will help inform a complex and extremely important conversation.

We've known for a long time that environment influences health. What's exciting is that we're now uncovering, in more detail than ever before, just how much of an influence those factors have. And most importantly, we are beginning to understand the ways to intervene with precision to prevent disease and promote life-long health. These studies -- along with others that are underway -- suggest that's the direction we're heading in, following in the footsteps of pioneers like John Snow to once again redraw the frontiers of population health and medicine.

Lloyd Minor, MD, is dean of the Stanford School of Medicine and a professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. A longer version of this piece originally appeared on his LinkedIn page.

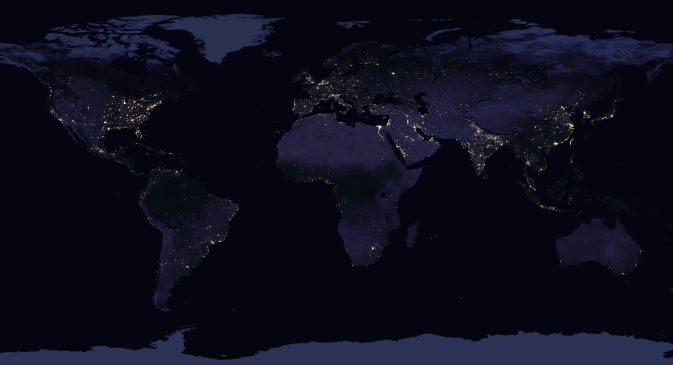

Image by NASA