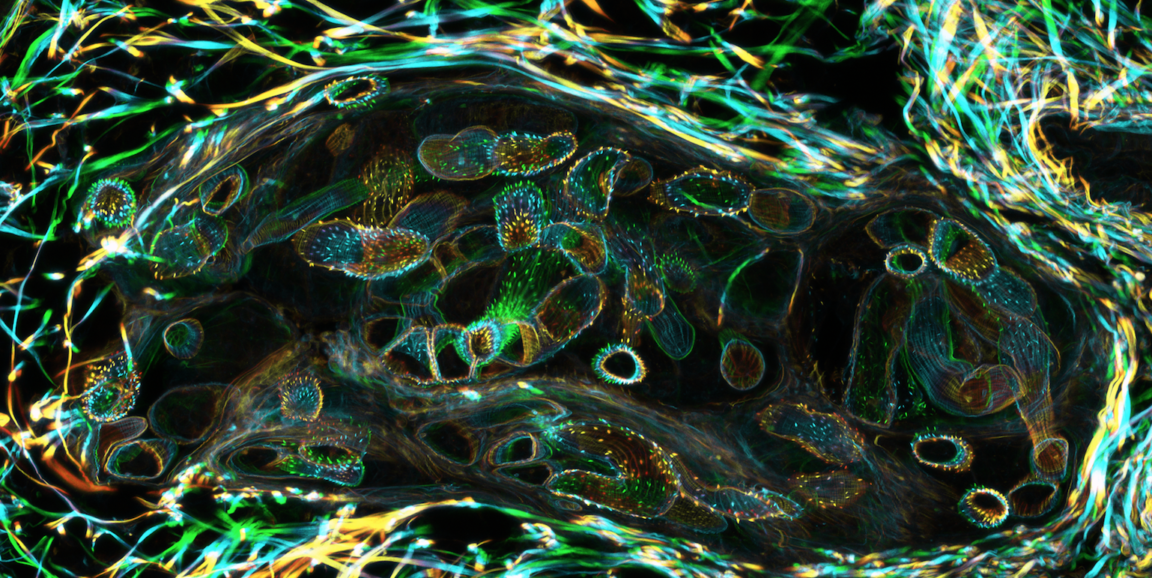

Not everyone would turn an image depicting the insides of an infected snail into a custom throw pillow, but I did. That image (above) came from the lab of Bo Wang, PhD, an assistant professor of bioengineering, and it shows a cross section of a snail infiltrated by the schistosome parasite.

Wang's research in the tiny, flesh-burrowing parasite is one of five bizarre and even baffling research projects featured in a Stanford Medicine magazine article that highlights some of the basic science going on at Stanford. The story, "Beyond the bench" spotlights body-snatching sea squirts, marvels of molecular biology and the most gorgeous parasites you've (probably) ever seen.

And here's the kicker: The science, while cool, is also helping scientists understand more about how human biology and disease work on a fundamental level.

Take the flower-shaped sea squirt for instance -- these tunicates engage in something called stem cell competition, which allows one sea squirt to merge with another and genetically overtake it.

From the story:

...[That competition] made [Irving Weissman, MD, director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine] wonder if blood stem cells might compete with each other in a similar way, and if that could play a role in aging and the development of cancers.

His team later demonstrated that this was the case and that human blood stem cells can acquire mutations that make them dominant over other normally functioning blood stem cells. The finding has already started to map out how faulty human stem cells can snowball into diseases like leukemia, a cancer that affects bone marrow.

As for the (perhaps surprising) promise of parasites, Ellen Yeh, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of biochemistry, of pathology, and of microbiology and immunology, studies a peculiar part of the malaria parasite called the apicoplast.

Yeh describes the apicoplast as one of the critical "organs" in the malaria parasite, Plasmodium, and she's working to figure out its exact role in the Plasmodium life cycle and whether it can be shut down in an effort to develop anti-malarial drugs. Researchers are already tampering with the apicoplast, trying to stop its development in the parasite:

It's scary and exciting at the same time because we don't know what the mechanism is [for apicoplast formation], but we can see the end result of eliminating ... enzymes [involved in its development]. We see that the apicoplast is gone and that the cell can't survive; now we just need to figure out how that happens.

Photo by Bo Wang