Since 1984, when the death of Libby Zion, an 18-year-old patient who died within 24 hours of an emergency hospital admission was proposed to be linked to resident workloads, there has been an ongoing attempt within the medical field to better monitor the often over-burdened jobs of physicians-in-training.

The primary solution has been to cut down on the amount of time they're on duty. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education limited work time for residency training programs across the country to a maximum of 80 hours a week. Many were working upwards of 120 hours a week, so this was an improvement. But years later, there is still little evidence that it's led to better outcomes for patients or residents.

In a recent study, Stanford researchers proposed a new method that might help lead to a better understanding of these often crazy schedules. Analyzing what they call "digital data streams," such as pager records, to measure how busy residents are during a specific shift could shed light on factors that are driving physician burnout, and prevent potential errors in patient care, the study said.

"This was an idea that came up during my own residency," said Amit Kaushal, MD, PhD, adjunct professor of bioengineering and clinical instructor of medicine at Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, where he now leads teams of Stanford residents. "It became clear to me it wasn't just how long I was in the hospital but what actually happened while I was there that made a difference.

'We could have an uneventful 80-hour work week and feel fine or a week with shorter but much more intense hours -- whether because we were caring for a lot more patients, or we had very intense experiences, maybe with patients and families dealing with tough end-of-life situations -- and feel much more run down.'

The study by Kaushal and co-authors Laurence Katznelson, MD, professor of neurosurgery and of medicine and associate dean of graduate medical education, and Robert Harrington, MD, professor of medicine and chair of the Department of Medicine was published in npj Digital Medicine.

Kaushal, a bioengineer and self-described "data guy," who also serves as director of the undergraduate major in biomedical computation, came up with the idea of collecting data from the pagers used by the residents during their work shifts.

It just made sense that the greater the number of pages responded to, the busier the residents were, and the greater the workload or work "intensity," as the researchers refer to it in the study.

"When I went back over my own paging data, there were some nights when the number of pages was in the single digits, and others where a page a page came in every five minutes, nonstop, for two hours straight. Those are the nights you remember as residents," Kaushal said. He continued:

It can feel like everything is coming at you at once -- the ER may be calling you to evaluate multiple patients for admission, and all of a sudden you find out there is a patient being treated for leukemia who suddenly spiked a fever. Before you've gone there, another two pages come in for maybe something more routine, like the patient who wants sleeping medicine.

It's up to you to quickly assess what's urgent and what's not, and double and triple check that you're not letting anything slip through the cracks -- all while moving 100 miles an hour.

The researchers collected two years of pager data with help from the Stanford University IT Paging and Messaging Services office, which comprised more than half a million pages, making it one of the largest studies of paging data.

Interns, the first year residents, received about 3,000 pages a year on average, almost twice the number that second- or third-year residents received. And, by far, the night shift intern received the most pages, which corresponded with Kaushal's memory of what it was like working that shift that first year.

The number of pages during the night shift also varied considerably from night to night, as much as from less than 10 on a slow night to more than 80 on a busy one.

To confirm that a high number of pages meant that those shifts were the busiest, researchers also examined patient admissions data that showed that the longer the wait time for a patient to be admitted from the ER into the main hospital -- a metric known to be associated with high hospital-wide workload -- the higher the number of page calls.

"The question is still open in terms of what kind of workload management is best for residents, but digital data streams could provide additional information," Kaushal said.

Pagers are slowly being phased out and replaced with more advanced technological devices, such as an iPhone app that pings a resident for calls. But similar methods could be used to collect workload intensity data from other devices and perhaps be used to put prevention methods in place, the study said.

"These digital tools may help take us to a place where, instead of just reporting retrospectively on high workload conditions, we actually have the data and analytics to do something about it in real time."

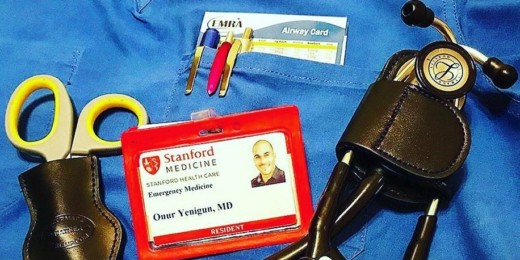

Photo by wolfgangfoto