Stanford scientists have developed an imaging agent that can track down multiple types of cancer -- and fortuitously -- a deadly lung disease, too.

The new imaging molecule, created in the lab of Sanjiv "Sam" Gambhir, MD, PhD, professor and chair of radiology at Stanford, is known as a tracer and it works in conjunction with a machine called a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner.

Often, PET scanners are used to monitor the human body for cancer cells. Now, thanks to a little serendipitous biology, Gambhir and colleagues have created a tracer that not only identifies pancreatic, cervical and lung cancer, it also flags a particularly hard-to-detect lung disease that hardens lung tissue, called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, or IPF.

Initially, Gambhir and his team were after a new way to spot the first signs of pancreatic cancer, which is particularly hard to catch early. With that goal in mind, the scientists developed a tracer that clings to a special protein called integrin alpha-v beta-6, a molecule that sticks out on the surface of pancreatic cancer cells. Under a PET scan, the tracer glows due to its emission of radioactivity, which allows doctors to see exactly where the tracer is docked in the body.

"We didn't intend for our tracer to have multiple functions," said Gambhir. "At that time we had no idea that levels of alpha-v beta-6 may also be elevated in lung diseases such as IPF.

The realization came after a conversation with colleagues in the pharmaceutical industry. "They'd asked if we'd ever considered targeting IPF with our tracer, since there are some drugs for the disease that target that very protein," said Gambhir. Gambhir said they hadn't, but with IPF's notorious reputation as a disease that can kill soon after symptoms appear, it made sense to pursue detection for cancer as well as detection and monitoring of the lung disease.

Next, Gambhir and his team set up a clinical trial to test the tracer.

"Making a new PET scan tracer is like making a new drug from scratch. You have to take that drug all the way from concept into the first time it's injected into a human -- and it's subjected to near the same scrutiny as any new drug," he said.

The trial included patients who were healthy (the controls) and those who were known to have one of the diseases (cancer or IPF). Although it was small -- just a handful of patients from Stanford and several more in China -- the results clearly indicated the tracer is accurate and has detection potential. (There are, Gambhir noted, a couple other places in the body that naturally contain relatively high levels of alpha-v beta-6, such as some parts of the stomach, and while it's not a deal breaker for the tracer, it's something to take note of before interpreting a PET scan for disease.)

A paper describing the work appears published in Nature Communications.

"With approval from the Food and Drug Administration, we were able to show that a clear signal for both diseases comes through on a PET scan -- and it's safe," Gambhir said.

Just how early this tracer can spot cancer, pulmonary fibrosis or potentially other types of lung disease is still up in the air -- it will take more funding and more patients to determine that, for which the team is already planning. But a participant in the study who was supposed to be a normal, healthy control (and whose identifying details have been altered for her privacy) did provide some interesting data that suggest the tracer could potentially enhance early detection for IPF.

"There are known risk factors for pulmonary fibrosis that elevate your chances of developing the disease -- things like coming into close, repeated contact with bird/animal droppings or environmental exposures like coal mines and silica dust," said Gambhir. "This participant worked closely with birds for her job, and through our tracer, we did see some signs of what looked to be increased tracer uptake which might be indicative of early pulmonary fibrosis."

Whether that heightened detection of alpha-v beta-6 truly points to early-stage IPF cannot yet be determined. "But it's enough to raise suspicion, and it could be a sign that the tracer is able to pick up on signs of IPF much earlier than the traditional detection methods used today."

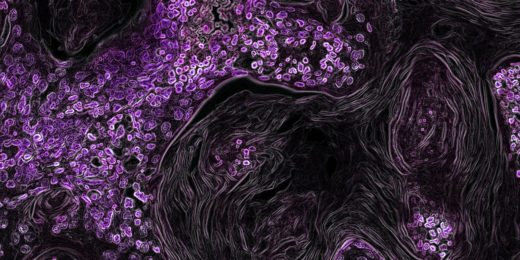

Photo by Liz West