The experience that most dramatized for me the absurdities of the American medical system happened thousands of miles from the United States.

A few years ago, I was visiting a university in a provincial city in Denmark. I developed an abscess in my hand, which I suspected, from previous experience, would require an antibiotic. I was directed to a nearby hospital, where I explained my problem at the front desk. Someone showed me to a small consultation room and said, "Wait. The nurse will come." I waited, the nurse came in a few minutes, looked at my hand and said, "Wait. The doctor will come."

The doctor came, examined me, and said yes, I did indeed need an antibiotic. Then he turned around in his chair, opened a cabinet behind him, took out a bottle of pills, and gave it to me, explaining that I should take two a day for 10 days and he thought the infection would be cured. He asked me what had brought me to Denmark and we chatted for a few minutes.

Then, as we both got up to leave the room, I asked him, "Where do I go to pay?"

He answered simply, "We have no facilities for that."

No facilities for that. I've remembered the phrase ever since and think of it every time I get a medical bill, talk to someone in a physician's office about what insurance will cover, and receive pages of itemized charges showing what Medicare has paid for, what my private insurance has paid for, and what I still have to pay for.

And then, of course, I think about all the tens of millions of people in this rich country of ours who have no insurance at all, who wait in long lines at public hospitals or simply despair of seeking any help for fear of the cost. And I think of the people I know who've been charged for the cost of an ambulance picking them up in an emergency.

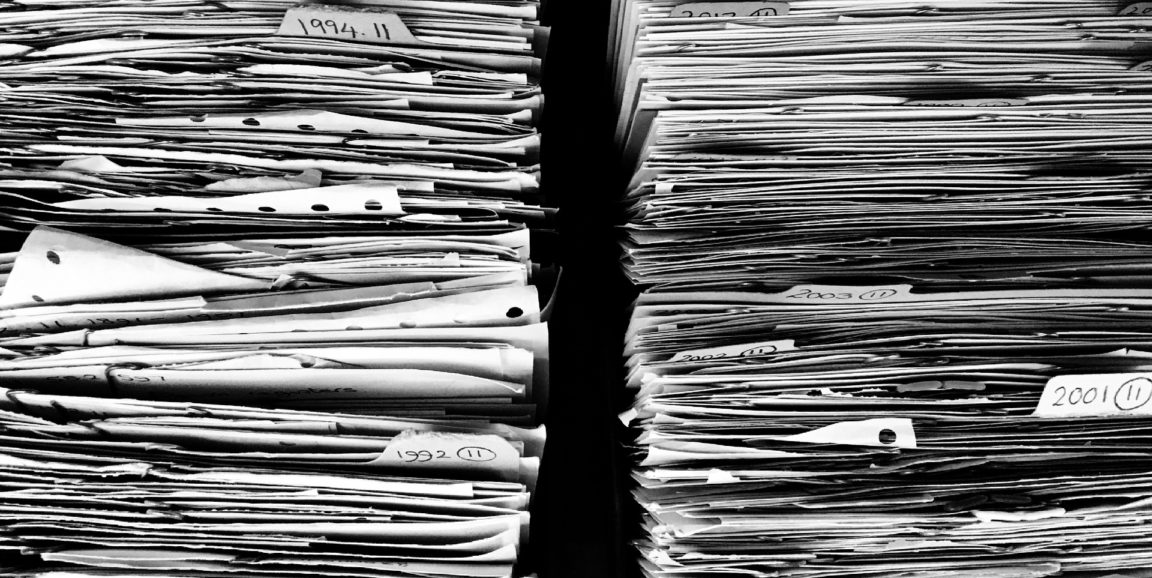

In the richest country in the world, that we still don't have comprehensive national health insurance that covers everyone, and covers everyone equally, is one scandal. Another scandal is the vast flood of paperwork required to get claims paid, and the vast amount of time medical workers spend arguing by phone or email with insurers about what can get covered.

Insurance Business America, a trade publication you wouldn't expect to publicize such figures, recently shared that 18% of American health care spending has to do with filing paperwork and processing insurance claims, and that the average doctor spends $68,000 to $85,000 a year dealing with such matters.

How much simpler it would be to have universal health insurance, so that every doctor, nurse, and physician's assistant could say, "We have no facilities for that."

Adam Hochschild writes on issues of human rights and social justice. He is the author of nine nonfiction books, most recently Lessons from a Dark Time and Other Essays.

This piece is part of Scope@10,000, a series of original narrative essays from writers, physicians and thinkers in honor of Stanford Medicine's Scope blog publishing 10,000 posts.

Photo by Ag Ku