For 40 years, scientists have struggled to develop chemotherapy for a lethal childhood brain tumor called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. More than 200 clinical trials have failed, even though many of the drugs tested can fight other cancers. The five-year survival rate for children with DIPG is less than 1%.

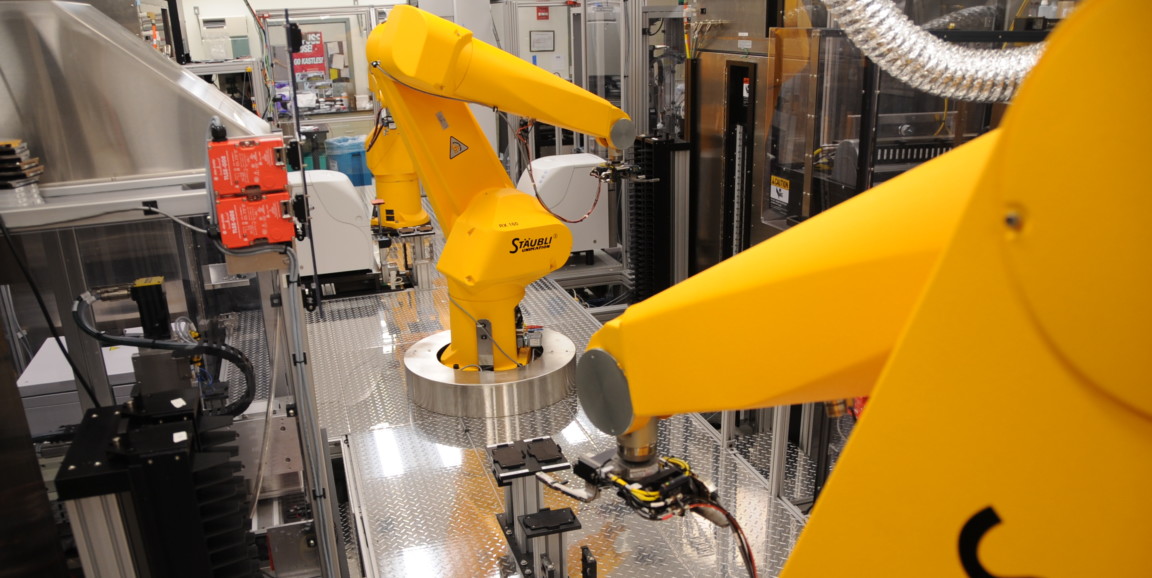

Recently, Stanford pediatric neurooncologist Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, teamed up with experts at the National Institutes of Health on a different approach: With help from big yellow robots at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, they applied more than 9,000 two-drug combinations to cultured DIPG cells to search for a pair of existing drugs that would synergize against the deadly tumor.

"The goal of this study was to identify two drugs that work together better than one," Monje said. The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, pinpoint a pair of drugs called panobinostat and marizomib, which together modestly increased survival time when tested in animal models of the disease.

"The high-throughput combinatorial strategy lets us get a lot of data in one fell swoop," Monje said, "After that, we can go back and untangle the mechanism of why two drugs might work well together."

The scientists began by individually testing 2,706 approved and investigational drugs from the NIH's drug libraries on six lines of DIPG cells from Monje's Stanford lab, generating nearly 20,000 data points describing the cells' responses to individual drugs.

From more than 7 million possible two-drug combinations, the scientists then chose about 9,000 drug pairs for the next round of testing. The researchers prioritized pairs of drugs that came from different mechanistic classes, were already approved or close to approval for human patients, and could cross the blood-brain barrier to reach a brain tumor.

Both the individual drug tests and the tests of drug pairs made use of the NCATS robots, shown in the photo above. The robots can test tens of thousands of drug combinations in just a few days, far outpacing what human lab techs would be able to accomplish.

Panobinostat and marizomib, both of which were good at killing DIPG cells on their own, were each tested with many other drugs as well as with each other. The entire resulting data set is publicly available for other scientists to learn from.

Since the combination of panobinostat and marizomib worked best at killing DIPG cells, Monje's team conducted follow-up studies at Stanford to figure out how the drugs work together. The two-drug combination interfered with the cancer cells' ability to make a compound known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, a key player in cells' energy use. Interestingly, while direct interference with NAD metabolism kills any cell, the two drugs synergize in a roundabout way that only causes problems for DIPG cells, leaving nearby healthy cells alone.

"It was not obvious before our study that there was this metabolic vulnerability," Monje said. The drug combination is now being moved toward a clinical trial in children with DIPG.

Though finding the two-drug combination represents an important step forward, it is not likely to be enough to cure DIPG, Monje cautioned. In addition to targeting the cells' internal workings, as these drugs do, research suggests it will be necessary to disrupt how the tumor interacts with nearby healthy brain cells, and to develop immunotherapy against the cancer. Researchers aim to develop a treatment that combines all three strategies.

One other notable result from the new research was that a drug called selumetinib -- which works against some types of brain tumor -- should not be used for DIPG.

"What we found was that, in some DIPG cells, this drug actually seemed to make things worse," Monje said. Rather than inhibiting the DIPG cells, the drug stimulated their growth.

"The misses in these studies are as important as the hits," Monje said. "They help guide the field away from exposing children to medications that are unlikely to be beneficial to them."

Photo courtesy of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences