People sometimes assume physicians either have the ability to talk to patients about difficult subjects -- or they don't. Actually, it's an ability that everyone can learn and then hone, palliative care expert Stephanie Harman, MD, told me.

"These are inherently teachable skills," Harman said. "How do we teach someone to recognize emotion and respond to it? How do we teach someone to strip away all the medical jargon and give a really clear headline of what's happening, and then pause and give space for a patient and family to respond?"

Harman and other educators at the Stanford University School of Medicine, including Charles Prober, MD, and Jonathan Berek, MD, executive director of the Stanford Center for Health Communication, are leading the way to ensure current trainees have opportunities to learn these skills and practice difficult conversations in realistic, consequence-free environments.

One course, called "Managing Difficult Conversations," was based on a Graduate School of Business course led by Irving Grousbeck, MBA, a successful businessman and entrepreneur and co-director of the Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at Stanford Business School.

Grousbeck approached Prober in 2007, hoping to extend the course to medical students in recognition that there are some general principles that can help make these conversations more successful, irrespective of subject matter, and that business and medical students could learn more from one another.

Prober agreed and the joint course -- featuring guest clinicians in student-to-student and student-to-clinician role-playing -- was launched, instantly drawing more students than it could accommodate, said Prober, who taught the course with Grousbeck for ten years. He now co-teaches with Bill Meehan, MBA, a former senior director at McKinsey and the Raccoon Partners Lecturer in Strategic Management at Stanford's Graduate School of Business.

In one scenario explored in the course, students interact with Meehan, who draws upon his personal experience receiving a multiple sclerosis diagnosis to role-play with the students.

Meehan's case is laid out for students as, "a conversation around a bad diagnosis, how to convey it to the patient, and how the patient gets guidance on how to convey it to his family," Prober explained.

Case studies like Meehan's are the backbone of the course: Examples of conversations about real scenarios are scripted by a case writer who creates pseudonyms for patients and adds "fictional spice to them to make them more compelling," Prober said.

One case involves a child who fell into a swimming pool and drowned. Students must navigate the conversation between a father, who fell asleep in front of the TV, and his angry, anguished wife.

For students, role-playing with a patient who lived the experience is valuable, the instructors said. The students hear how the information they convey was received, and experience the emotional impact of the situations.

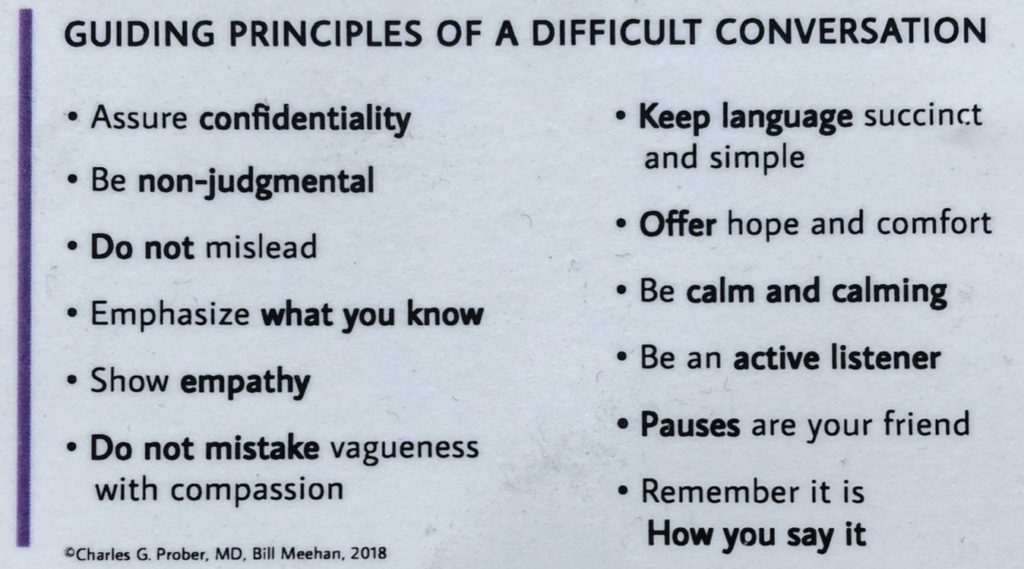

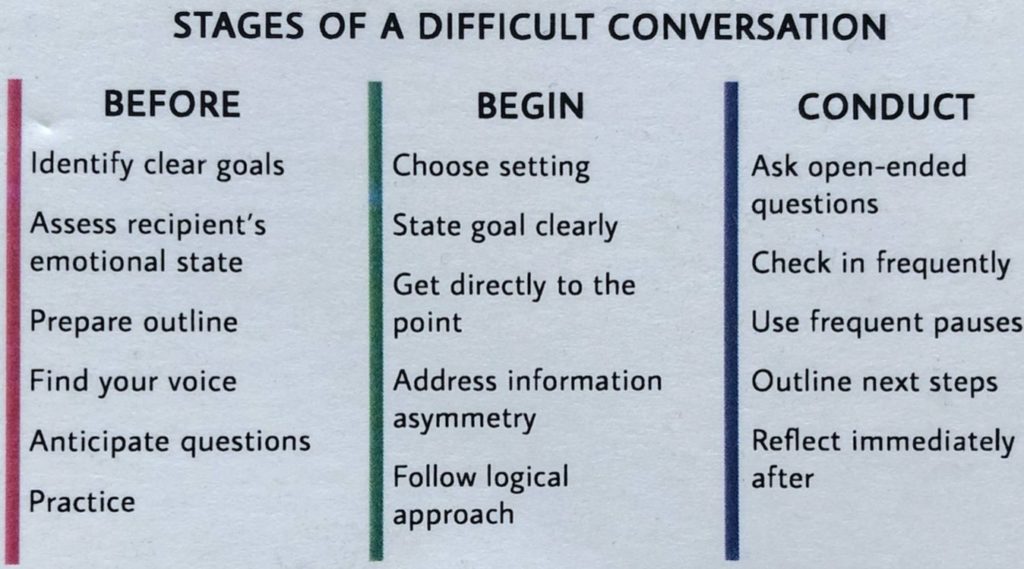

A two-sided business card offers tips created by Prober and Meehan for students in the course "Managing Difficult Conversations."

This fall, Prober will also teach "Challenging Conversations," with Berek, the director of the Stanford Health Communication Initiative. Berek describes the course as a "series of vignettes on a different challenging area of medicine."

Harman and other faculty members will join sessions on communication techniques for medical errors, interpersonal challenges, easing pain and suffering, and dealing with rage and sorrow.

Receiving a life-threatening diagnosis or discussing death, "is a critical moment in that patients life's journey," Prober said. "It needs to be handled with the utmost care."

"I was 14-years old when my father died in an emergency room from a massive heart attack," Prober said. "And I remember when the person came out of the room. You bet I remember. The way [the news] was delivered was not bad, but it is forever burned into your mind."

This is third in a series of Discussing Death blog posts designed to help people have more helpful and meaningful conversations about end of life care and death.

Photo of Charles Prober, MD, by Norbert von der Groeben