Four of us sit around a faux wooden classroom table with our pathology professor. We each look at the autopsy report. It's my turn to read.

"The patient presents to the ED via ambulance as a code-3," I say.

"Anybody, what's a code-3?" asks our professor. Almost impulsively, I say, "Coma?" We look at each other and back at him. "Lights and sirens," he says, using shorthand for a medicalized code meaning the patient is gravely ill.

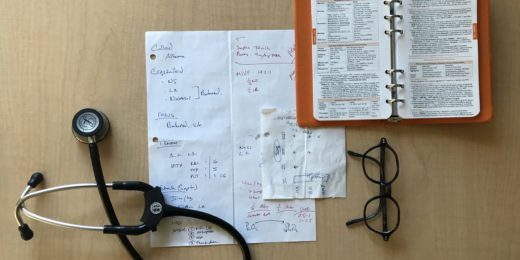

We nod and continue to pick apart the case together, line by line. As part of this elective pathology class, we learn about illness through death. First, we read an autopsy report. Then we examine the autopsy specimens -- the patient's organs. Then we look at the tissues under a microscope.

Halfway down this autopsy report, I read, "Patient is unresponsive." Followed by, "Pulseless electrical activity." Followed by, "Deceased."

We discuss the different possibilities for how the resuscitation attempt progressed and what exactly may have caused the patient's death. Then we go into the lab to examine the autopsied organs -- heart, liver, lungs, intestines, arteries, lymph nodes, spine, kidneys, spleen and brain -- to see if our assessment could be correct.

The laboratory is nothing like the ones in forensic TV dramas. It's well-lit, and rays of sunshine peek in through large windows. We gown, glove and mask. The stench of chemicals and old specimens stings my nose.

We examine the now cold and pulseless heart that beat -- albeit erratically -- in a person just days before. It's striking.

I wonder how much time separated this moment from another moment, in which this person and I could have been going about our lives in similar ways, sitting in our respective kitchens sipping coffee and planning out to-do lists. Now, I examine the chambers and blood clots of the grayish heart and hypothesize with fellow students about the cause of death: Hardened plaques in his coronary arteries weakened the vessel walls, which ruptured and bled around the heart. Its beats became volatile, and the heart exhausted itself into stillness.

During most of the first two years, our science of medicine courses are structured like this elective, teaching us through patient cases. Each case is a story about how the person became sick, when they saw a provider and the progression of actions taken to treat the disease. In the middle of case sessions, we meander over to a table to view specimens from different patients.

Some are examples of "healthy" organs. Others are "pathological." When it comes to diseased specimens removed from a body, there are some a person can live without: a uterus, gonads, parts of the intestines. Others might be swapped for a transplant -- heart, lungs, kidneys. Seeing those organs lined up on moistened towels on the tables outside our classrooms, I can say to myself, these people might still be alive.

That is not the case for other specimens -- brain, spinal cord, vertebral column. When I see these organs on a table, I know these people have died.

There was a point in my life when I understood death simplistically -- I was told someone passed away, and soon after that I attended their funeral. There was no in-between. Now I have experienced the in-between.

Almost two years into medical school and three years into dissecting cadavers and learning from the organs of deceased bodies, I'm grateful that I haven't lost the part of me that thinks about a person's story -- in some part thanks to professors, who remind me of the subtle difference between documenting an "87-year-old male" and an "87-year-old man."

I'm inured enough -- desensitized to picking up the specimen (most of the time), but still able to hold onto respect and compassion for the person whose body that specimen came from, and the people out there who might be suffering because of its loss.

It matters to me, when holding a specimen or discussing a patient, that I not lose sight of the story and life behind the disease. Each case I learn about is a journey that's become part of my own: part of how I understand medicine and part of how I'll treat and care for patients throughout my career.

Stanford Medicine Unplugged is a forum for students to chronicle their experiences in medical school. The student-penned entries appear on Scope once a week during the academic year; the entire blog series can be found in the Stanford Medicine Unplugged category.

Lauren Joseph, LoJo, is a second-year medical student from California. She enjoys reading and writing, and her written work has been featured in STAT News. When she's not studying, you can find her running, enjoying the sun, and laughing with friends and family.

Photo by Kurt Bauschardt