Running is a low-cost form of exercise with all kinds of benefits for health and well-being, yet some people don't enjoy it. What if you could attach a device to your leg that makes running easier -- and makes you faster?

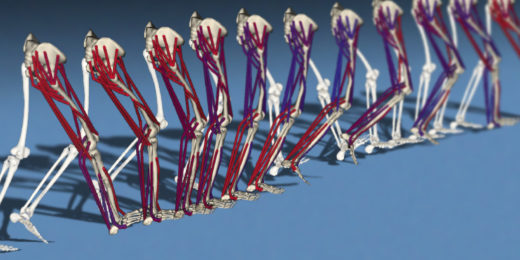

Such a device -- in the form of an ankle exoskeleton -- may some day come from research led by Steve Collins, PhD, associate professor of mechanical engineering. In a recent paper, published in Science Robotics, Collins and his colleagues revealed the extent to which two types of prospective ankle exoskeletons could help make running easier. They specifically investigated the potential of a device with an on-board motor versus one that uses a spring but no motor.

Their tests suggested that a motor-powered exoskeleton could reduce the energy cost of running by 15% compared with running without an exoskeleton. In contrast, running with a spring-based device increased energy demand, making it 11% harder than running exoskeleton-free.

The researchers tested these exoskeletons using a system that attaches like an exoskeleton but emulates the two assistance types -- motor and spring -- using off-board motors. This system allows the researchers to try out different exoskeleton assistance types without having to build them.

The motor-powered assistance that they emulated helps extend the ankle at the end of a running step using action similar to a brake cable, except this cable is routed through the back of the exoskeleton from the heel to the calf. The spring-based emulation mimicked what it would be like to run with a spring running parallel to the calf, storing energy during the beginning of the step and unloading that energy as the toes push off.

Eleven experienced runners tested the two exoskeleton emulations by running on a treadmill. The researchers monitored their energetic output through a mask that tracked how much oxygen they were breathing in and how much carbon dioxide they were breathing out.

"Powered assistance took off a lot of the energy burden of the calf muscles. It was very springy and very bouncy compared to normal running," Delaney Miller, a graduate student who works in Collins' lab, said in a story for Stanford News. Miller is working on these exoskeletons and also helping test the devices.

"Speaking from experience, that feels really good," she said. "When the device is providing that assistance, you feel like you could run forever."

The lackluster performance of the spring-based exoskeleton surprised the researchers because previous studies have shown great potential for spring-based running assistance. But they emphasize that this form of assistance may still be useful if exoskeleton designs become more sleek, and that they are likely to be cheaper than motor-powered options.

The fact that the motor-powered exoskeleton emulation did so well was surprising too -- and exciting. Their findings indicate that a runner using the powered exoskeleton could boost their speed by as much as 10%.

"These are the largest improvements in energy economy that we've seen with any device used to assist running," Collins said. "So, you're probably not going to be able to use this for a qualifying time in a race, but it may allow you to keep up with your friends who run a bit faster than you. For example, my younger brother ran the Boston Marathon, and I would love to be able to keep pace with him."

Image by Farrin Abbott, Stanford News Service