Even before COVID-19, our medical school courses on infectious diseases featured videos -- little narratives on make-believe patients.

"She deteriorated quickly, growing less alert with each passing day," explained the springboard video on Clostridium difficile, the bacterium that can cause diarrhea and dangerous inflammation of the colon. "Two weeks later, despite the best effort of her care team, Lydia passed away with her family at her bedside."

We found these videos compelling. Throughout our six months in these courses, my classmates and I sent texts to each other -- updates on the springboard videos -- as often as the blasé texts we send about pickup basketball: "Hey did you watch this week's videos? Can't believe the kid with hepatitis survives."

Now, keeping up with COVID-19, we're sending similar texts. Only this time we're discussing articles from newspapers and videos from academic sources. This time we don't have -- nor do we need -- a springboard video. Stuck at home like everyone else, we're seeing the virus unfold in real time.

"Just read a NYT article on a nurse in NY whose family came in with the virus and I'm wrecked," I wrote to a classmate just a few days ago. My friend replied, "Did any die?"

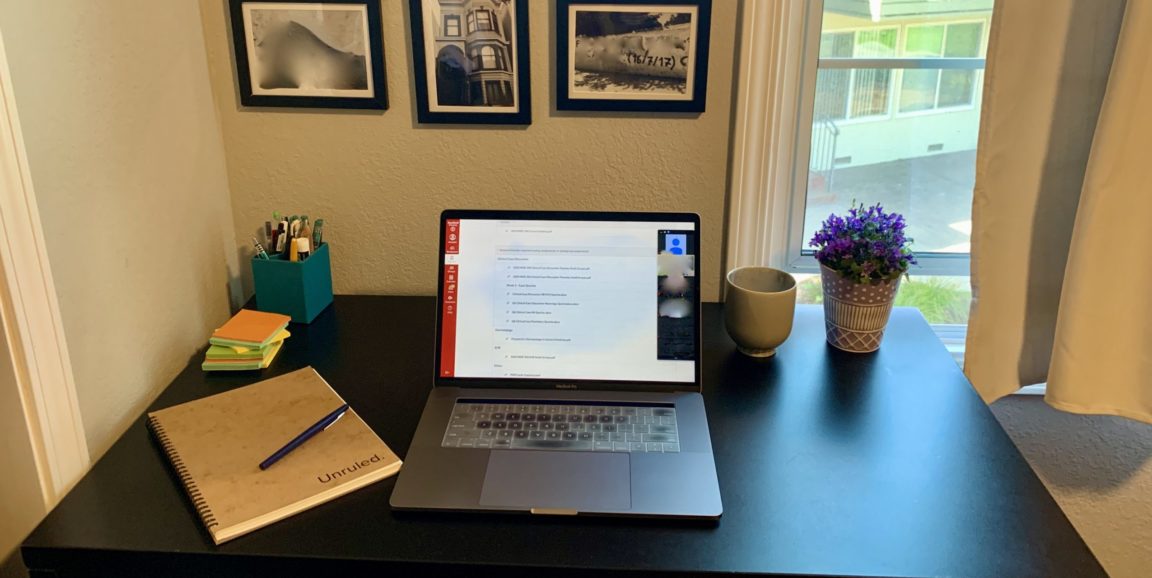

As the whole world is affected by this virus, so is our medical education. Preclinical medical students like me are walled up in our apartments or our families' houses, logging in online to video conference classes. The novel coronavirus sent us to hunker down in our homes, and it also became a subject of curriculum in the first week of our spring term.

In a two-and-a-half hour session, modeled after our microbiology course, our professors asked our small groups to compare and contrast the two big players in this infectious disease season -- influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2.

Rather than having us memorize a bunch of names and facts, they made each disease's life a story with heroes, villains, weapons and people accidentally hurt in the process. These microbes each had a path and a character arc; we were challenged to understand how, like the braided plot of a novel, a patient's story intertwines with the story of an infectious agent.

We also discussed how the microbiology of the novel coronavirus might affect its spread from person to person. Our professor asked: Based on what you know about influenza virus, what would your rationale be about wearing masks for all or a subset of the general population during this pandemic? We went on to have a long discussion led by faculty about the relative protection a mask might provide.

My professor indicated that we don't know that all masks are sufficient, because each type of mask's ability to filter out differently-sized molecules varies. But we think, she explained, that masks can block most droplets and help to slow respiratory droplet spread.

In a time like now -- with extreme uncertainty and frenetic energy -- I find comfort in the familiar: a session, albeit in my pajamas in my apartment, structured just the same as our course on other infections (of which there are many) in which we finish worksheets in small breakout groups.

The familiarity provides a semblance of normalcy amid the unfamiliar. This time, the infectious disease is not a concept. It's not a picture of what happened years ago. It's a picture of now -- of a virus that took my friend's grandparent, that spared my relative, and that scares people from going to the grocery store.

I feel really lucky to be in the place that I am -- to learn about things that matter to me and aspire to be part of a profession dedicating itself to the healing and dignity of human beings all over the world.

I'm even luckier to be taught medicine by faculty who start off our online sessions telling us how grateful they are to be teaching us, and share with us their renewed call and passion for practicing medicine during this crisis.

A lot of what's happening around me feels unexpected, but that's also what medical school prepares me for -- breaking down huge problems into smaller questions, one at a time. There are always new circumstances, new patient stories; and we are taught to apply what we know and critically assess a disease presentation with a holistic view of that patient in that time in history.

Stanford Medicine Unplugged is a forum for students to chronicle their experiences in medical school. The student-penned entries appear on Scope once a week during the academic year; the entire blog series can be found in the Stanford Medicine Unplugged category.

Lauren Joseph, LoJo, is a second-year medical student from California. She enjoys reading and writing, and her written work has been featured in STAT News. When she's not studying, you can find her running, enjoying the sun, and laughing with friends and family.

Photo by Lauren Joseph