A new technology aims to make tumors their own worst enemy in the fight against cancer -- and Stanford Medicine will be the first in the world to incorporate the treatment into the clinic.

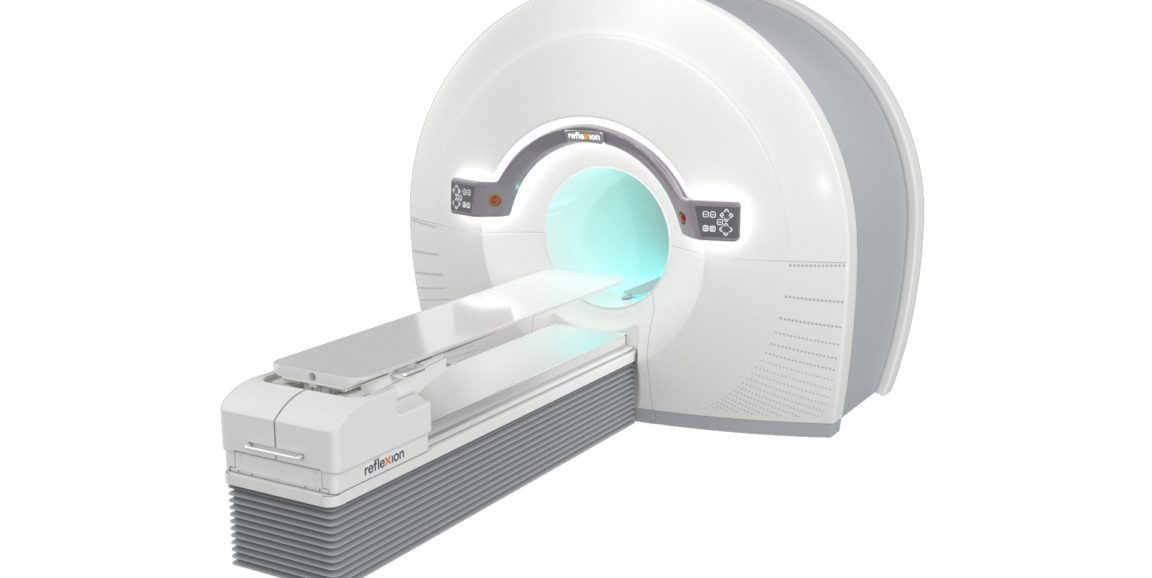

The first generation of a machine using this technology -- the X1, from the company RefleXion Medical -- harnesses positron emission tomography to deliver radiation that tracks a tumor in real time. This PET feedback allows the system to send beams of radiation to destroy cancerous cells with heightened precision.

Researchers hope that this "biology-guided radiotherapy" will increase accuracy, safety and efficacy of cancer radiation treatment. Stanford physicians plan to test the X1 later this year through clinical trials at Stanford Hospital. Their first step will be to obtain approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

"To my knowledge, this machine is the first of its kind. It combines two technologies - one traditionally used in cancer diagnostics, and one in therapeutics -- into a single technology," said Daniel Chang, MD, professor of radiation oncology, who will lead the clinical trial. "That's what makes this really unique."

Radiation therapy is often one of the primary tools used to treat cancer. But the therapy, which bombards tumors with high-energy particles that kill cancer cells, comes with a downside: The beam of destructive particles does not discriminate between cancerous and non-cancerous cells, and healthy cells are often damaged in the line of fire.

With this new technology, the PET scanner provides continuous feedback about the location of a tumor, based on the tumor's emissions, even if the tumor moves as a patient breathes. This PET feedback allows doctors to continue training beams of radiation on cancerous cells, even as the tumor's location shifts. With less risk of targeting healthy cells, doctors would be better able to zero in on tumors with higher doses of radiation, executing more accurate and precise radiation therapy, Chang said.

Samuel Mazin, PhD, co-founder and chief technology officer of RefleXion Medical, thought up the idea for the new technology while he was a Stanford postdoctoral scholar. Stanford Medicine will be the first to conduct clinical trials with the new machine. Both components of the machine -- PET scans and radiation -- have well-established safety profiles.

Chang and his colleagues hope that the technology will help open new avenues of research, such as clinical trials for patients with multiple tumors who may otherwise not be eligible for radiation therapy. The technology also could lead to studies to develop novel and more sensitive PET tracers -- molecules that reveal where cancer is in the body -- to assess the inherent biology of tumors and their response to treatment.

"We're excited about this technology for many reasons," Chang said. "It opens up new possibilities for treatment by allowing us to deliver radiation that tracks the tumor with extreme precision in real time -- something we're not currently able to do."

Photo courtesy of RefleXion ©2020. All rights reserved.