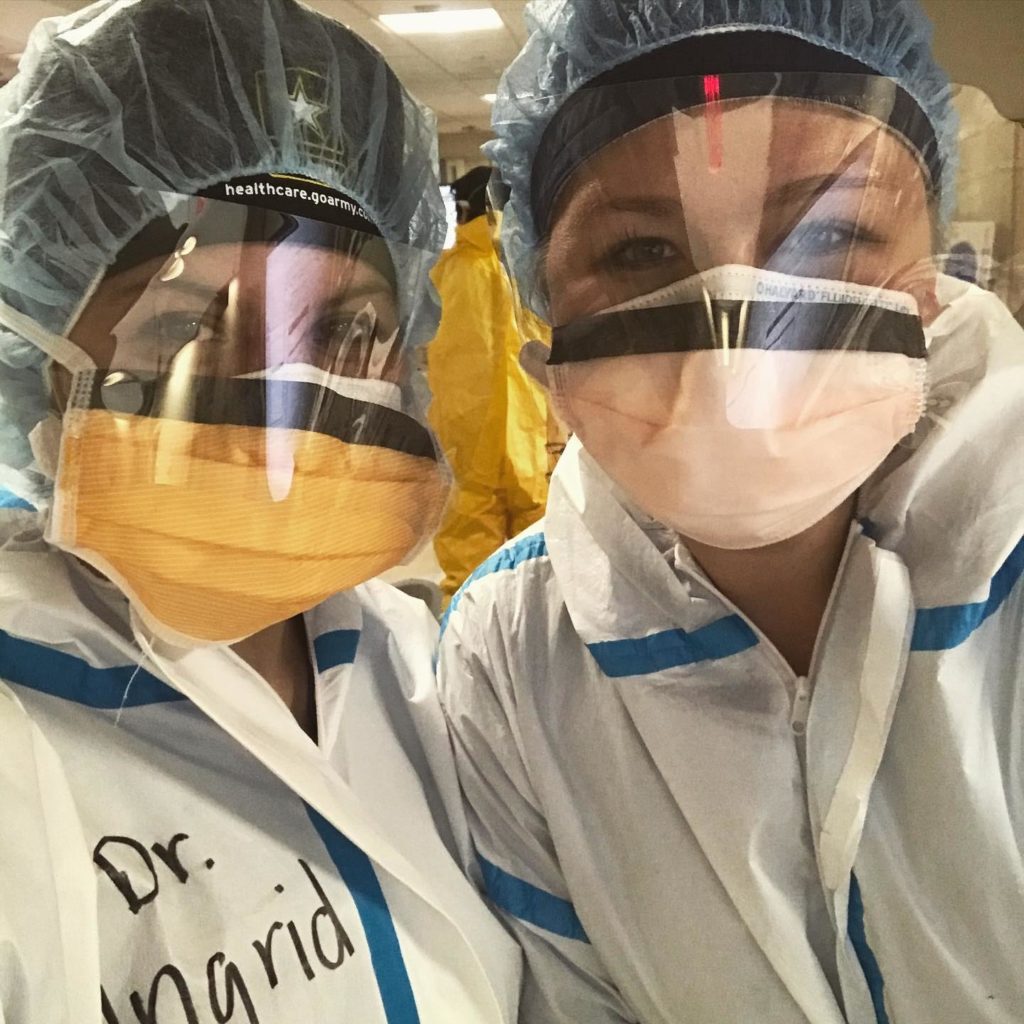

When Stanford post-doctoral scholar Ingrid Schmiederer, MD, went to New York in early April, she knew she was heading into the epicenter of novel coronavirus cases in the United States.

As a research fellow in the Goodman Surgical Education Center at Stanford Medicine, Schmiederer could have steered clear of working directly with COVID-19 patients during the pandemic.

But her heart was with friends she'd made during three years of surgical training at the New York-Presbyterian Queens hospital, where she is a resident.

"It didn't seem right for me to be working from home on my quiet couch in California, while my friends were coding patients every few hours and taking on more shifts to accommodate the growing number of patients," she said.

Bariatric surgeon Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, and nurse practitioner Kelly Sanderson, NP, had the same impulse. Salles is a Stanford scholar in residence, but isn't serving in a clinical role. Sanderson was part of a Stanford Health Care team prepped and ready to respond to a wave of COVID-19 patients.

When that expected wave of hospitalizations didn't materialize in Palo Alto, like many other medical volunteers around the country, they both went to New York to help fill the urgent need for health workers.

Patients could crash any moment

When Schmiederer arrived for her first day of work in Queens on April 12, the hospital had nearly 600 COVID-19 patients, 200 of whom needed critical care.

She took on various intensive care assignments during her five weeks there, including filling in for short-staffed nursing teams and treating people who were on ventilators because their lungs were failing. Half those patients were also on dialysis for kidney failure.

In her first week, two of her patients died each day. Other weeks, she performed CPR once or twice a day.

"These patients could crash at any moment, despite our best efforts," Schmiederer said. "It was a mental struggle to come to work every day, unsure of which patients would still be on the list and which of our efforts proved futile."

Frustrations of a mysterious illness

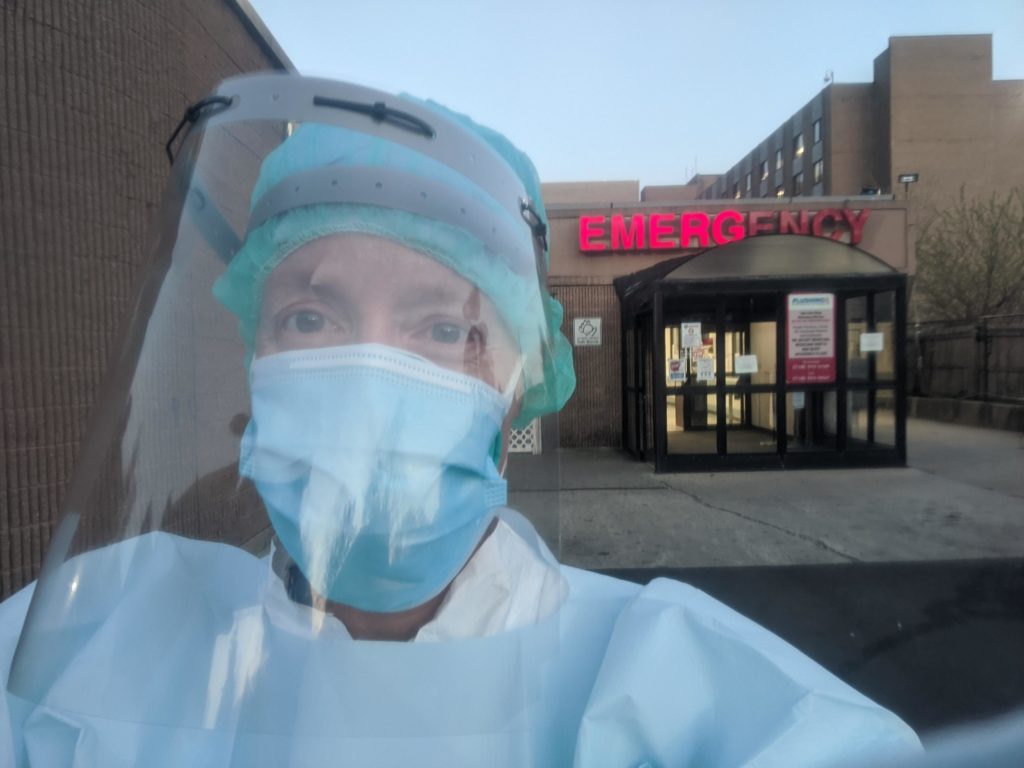

Arriving at a Brooklyn hospital in mid-April, Salles also saw at least one COVID-19 patient die each day she worked in the ICU -- and it was more death than she'd ever seen in her medical career.

Treating ICU patients for a largely mysterious illness was immensely frustrating, she said.

"That's what is really challenging for people in health care," she said in a Stanford Medicine 1:2:1 podcast interview. "We're used to being able to help and have medications and strategies that fix things. But here we were so limited, with so much uncertainly."

Keenly attuned to the stress of colleagues who had been treating critical COVID-19 patients long before she arrived, Salles worked every day of her two-week assignment.

"Some of them were living apart from their spouses, or their children, or sometimes both," she said. "I was very sensitive to what they were experiencing and the fact that they didn't really process any of it. They didn't have time or space to do that."

She also empathized with patients and their loved ones who could communicate only by phone or video chat, in an effort to protect against infection.

"That's hard, no matter what, but especially when you have people who are dying and their family is trying to send hopeful thoughts over a cell phone screen," Salles said. "That's the best they can do, but it's completely unsatisfying, disappointing and heartbreaking."

Providing a much-needed break

In late April, when Sanderson arrived at the Flushing Hospital Medical Center in Queens, the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths were starting to drop.

But the peak had left the hospital short on staff, personal protection equipment and backup help. The experience -- including the many patient deaths -- had been traumatic for staffers; Sanderson was among volunteers brought in to give them a much-needed break.

"Our being there gave them a bit of respite and a chance to talk about the trauma they experienced," she said.

Several COVID-19 patients remained, though, including many frail older patients with multiple health concerns. Sanderson, who manages minor illness and injuries in Stanford's outpatient Express Care clinic, tended to them at bedside.

"It's been a few years since I've gotten to do that kind of work," she said.

Feeling of resiliency and pride

Once back from New York, Sanderson, Schmiederer and Salles returned to their respective roles after following Stanford Medicine's COVID-19 guidelines for safely doing so.

Reflecting on their experiences, they talked about the resiliency and strength they found in health workers they encountered, and what it meant be among them, caring for COVID-19 patients in crisis.

Sanderson said she came away appreciative of New York and "grateful and kind" New Yorkers: "There's really a strong sense of taking care of each other there."

Salles felt it was important to share with a wide audience what New York hospital workers were going through; she documented thoughts and feelings about her time there on social media and through a video journal.

"I felt like I had a privilege, in a way, as a volunteer to be able to" record what happened, she said. "I felt a little bit like it was my duty to do that, along with the care that I was providing."

For Schmiederer, rounds with attending physicians and volunteer trauma specialists provided a learning opportunity that she appreciated. She expects the camaraderie she felt in New York to have a lasting impact.

"There is a level of trauma associated with this experience," she said, "but also a feeling of resiliency and pride in being in health care at this historic time."

Rachel Baker, Paul Costello and Mandy Erickson provided reporting for this article.

Photos courtesy of Ingrid Schmiederer, Arghavan Salles and Kelly Sanderson.