Two recent studies led by Stanford vaccinologist Bali Pulendran, PhD, show the value of tweaking vaccines to enlist the entire immune system -- not just part of it -- in preventing infection by HIV. This revelation may also inform efforts to develop vaccines that protect against many other pathogens, including the virus responsible for the current COVID-19 pandemic.

HIV is the virus that causes AIDS, a debilitating shutdown of the immune system. It infects 1.7 million people annually, causing some 770,000 deaths worldwide each year.

Though a preventive HIV vaccine isn't yet in sight, Pulendran told me in a recent interview, the new studies demonstrate the promise of two different ways of leveraging the body's existing immune machinery.

That could shake things up.

Awakening a dormant immune response

Most current vaccines work by raising antibodies to stave off an invading pathogen. Secreted into the blood and mucous membranes by immune cells called B cells, antibodies are proteins with specialized "tips" that are precisely tailored to glom onto a microbial pathogen, gripping it like a puzzle piece that's locked onto its mate. This hinders the pathogen's performance, ideally to the extent that it can no longer gain entry into the cells it's geared to infect.

In one study, which appeared in Nature Medicine, Pulendran and his colleagues tweaked the HIV vaccine to raise not only antibodies, but also an army of "killer T cells": immune cells that chase down cells infected by the pathogen. Killer T cells roam through the body inspecting tissues for signs of viruses and, upon finding them, destroy the cells that harbor them.

The investigators showed, in monkeys, that this alteration dramatically improved the durability of a vaccine's protection from the simian equivalent of HIV -- pointing the way to improved HIV vaccines for humans.

From a news release I wrote about this study:

The key to the new vaccine's markedly improved protection from viral infection is its ability -- unlike almost all vaccines now in use -- to awaken a part of the immune system that most current vaccines leave sleeping.

Tapping the innate immune system

B cells and killer T cells represent the two arms of the adaptive immune system, whose component cells proliferate, differentiate and mature only upon contact with an individual pathogen -- be it viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic -- rather than just pick fights with any old stranger they happen to encounter.

But it takes 10 days to two weeks for the adaptive immune system to ramp up. In the absence of an immediate defense, our bodies would be ravaged by even wimpy microbial marauders given free rein to colonize our tissues.

Enter Pulendren's second study, which implicates the innate immune system. This evolutionarily ancient alliance of cell-situated pattern-recognition sensors and first-responder immune cells discriminates between "us" (our healthy cells) and "them" (pathogens) in a rough-hewn "looks funny to me" sort of way; but beyond that, it doesn't make fine distinctions. It just trips off an influx of thuggish white blood cells to the site of the infection.

Those white blood cells savage the area with caustic chemicals, chew up suspicious objects and pump out inflammatory substances that bring in even more troops -- including roving adaptive immune cells now alerted to the pathogen's presence.

Boosting a vaccine's strength

In Pulendran's second study, published in Science Immunology, the team made use of a novel adjuvant -- a substance that boosts a vaccine's strength by stimulating the innate immune system. Think of the vaccine's pathogen-targeting components as its steering system and the adjuvant as a horsepower-enhancing fuel additive.

The researchers found that adding a new adjuvant to a vaccine substantially boosted the level of HIV-neutralizing antibody presence (as well as numbers and activity of various sets of cells instrumental in generating those antibodies) in monkeys.

This improved activation of the innate immune system and the previously cited work stimulating both arms of the adaptive immune system could spell big news in the vaccine world.

Pulendran told me these principles are likely to apply to research on vaccines against not only HIV, but also other pathogens, such as tuberculosis, malaria, the hepatitis C virus, influenza and the pandemic coronavirus strain.

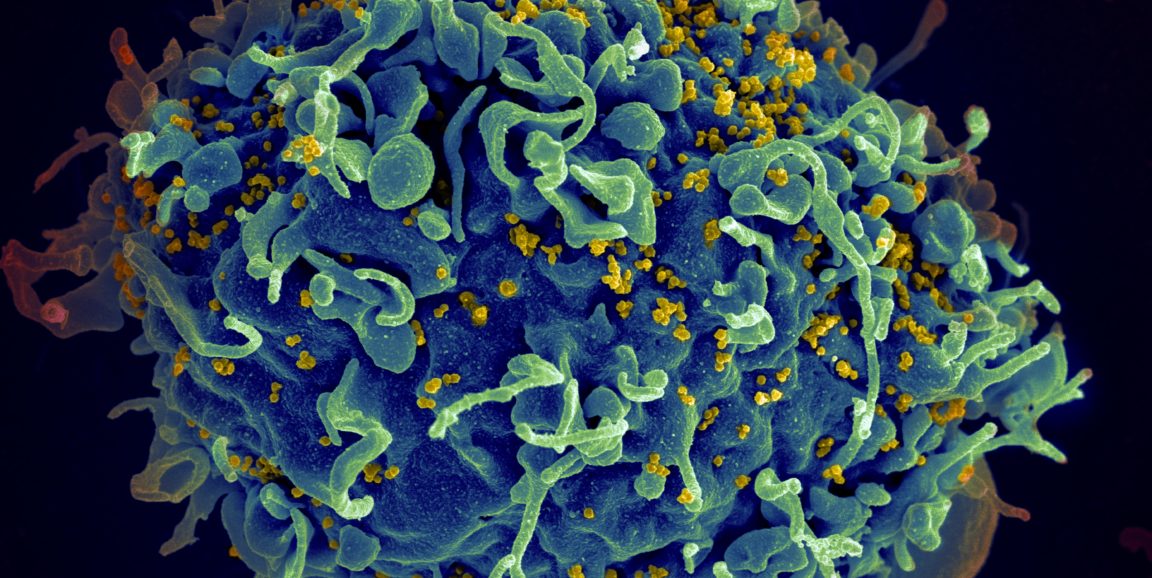

Image by Seth Pincus, Elizabeth Fischer and Austin Athman, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH