Researchers at the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine have discovered a molecule that can fuel the growth of breast cancer cells and, if blocked, offers a potential avenue for attacking breast cancer.

The discovery may be especially useful for "triple negative" breast cancers that don't currently offer a good target for therapy, the researchers said.

The molecule, called LEFTY1 by the researchers, plays a beneficial role in normal breast tissue remodeling that happens in response to changing hormonal cycles. However, it can also be used to promote out-of-control growth in breast cancer cells.

"A normal function of this molecule has been hijacked by the cancer cells to allow them to replicate unchecked," said Michael Clarke, MD, the associate director of the institute and senior author of a paper recently published on the research in Cell Stem Cell.

Blocking the signal from LEFTY1

LEFTY1 inhibits other molecules that change stem cells into more mature or "differentiated" cells. As cells mature, they lose their ability to make more of themselves.

"What we discovered is that when stem and progenitor cells are stopped from specializing, they default to a program of reproducing themselves," said Neethan Lobo, PhD, a co-lead author on the paper and a former postdoctoral scholar in the Clarke lab. "It's like if you stopped someone from becoming an adult, they stay a kid forever."

Two facts about LEFTY1 make it exciting for researchers. "One thing we saw is that the tumor-initiating cells, sometimes called cancer stem cells, are exquisitely dependent on this molecule," Lobo said. The researchers found that when they blocked the signal from LEFTY1, tumor-initiating cells in triple negative breast cancer tissue would stop growing.

The other exciting thing is that LEFTY1 affects cellular activity from outside the cell.

"A lot of things we look at are inside the cell, and are therefore not easily manipulated," said Jane Antony, PhD, a co-lead author on the paper and a postdoctoral scholar in the Clarke lab. "But this is released outside the cells, which makes it much more accessible to drugs and therapies we might administer."

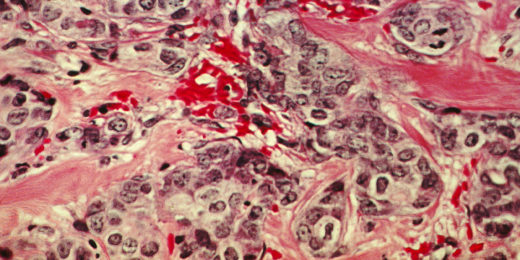

Image by vectorfusionart