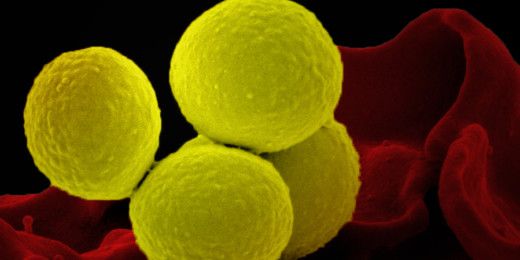

Bacteremia happens when bacteria enter a patient's bloodstream. It can cause an infection that progresses quickly, and can develop into sepsis, a life-threatening condition that can impair blood flow, cause clots and potentially lead to tissue damage, organ failure and even death. Every year, nearly 1.7 million Americans develop sepsis, the body's reaction to the blood poisoning, and 270,000 die as a result.

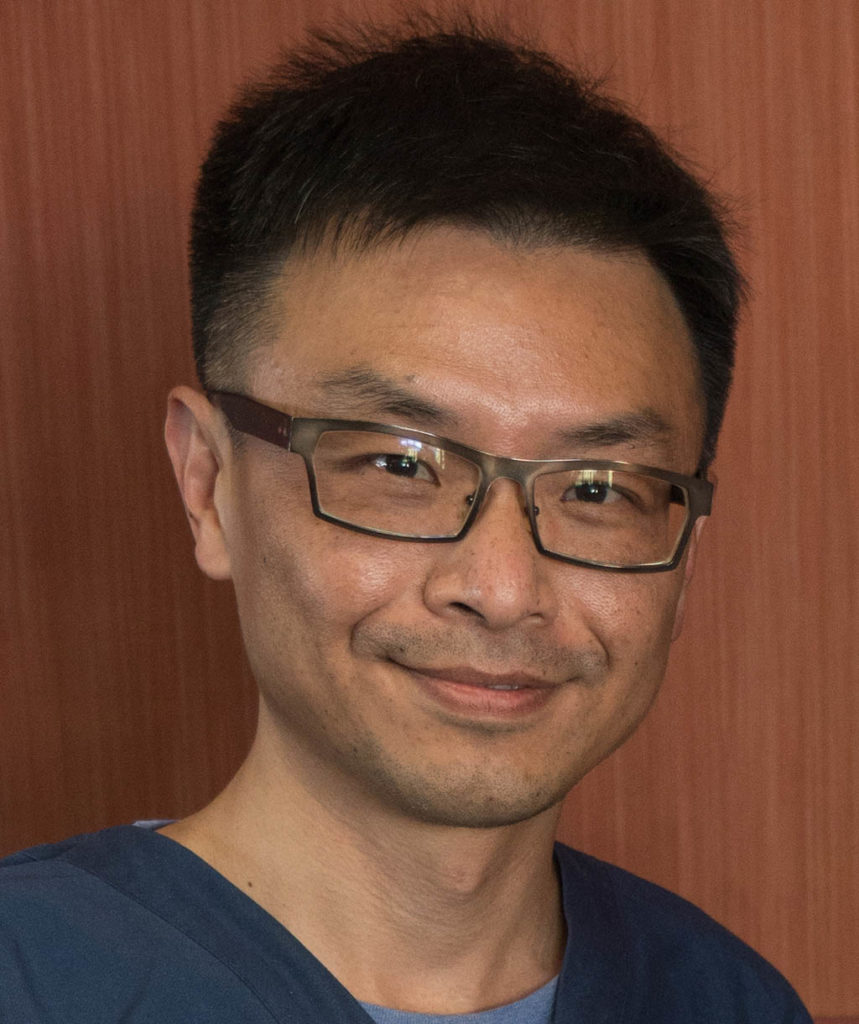

Standard diagnosis of sepsis relies on a blood test that typically takes days to complete -- precious time that can be critical for a patient's health. Samuel Yang, MD, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Stanford Medicine, is working to change this.

He has received two grants from the National Institutes of Health to develop a rapid sepsis test with high accuracy, building on recent advances in molecular microbiology, microfluidics, computer science and microscopy. He spoke with me recently about the work.

Our conversation has been edited for clarity and condensed for this Q&A.

Why, as an emergency medicine physician, is this issue important to you?

As a precautionary measure, emergency physicians often start broad-spectrum antibiotics when a bacterial bloodstream infection is suspected, only to find days later that the culture was negative. If we have a rapid test for bacterial infection that also helps determine which antibiotic will be effective for fighting that bacteria, a patient will have a better chance at recovery.

Also, unfortunately, antibiotic misuse promotes the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Infections that are drug-resistant are difficult to treat. We need to be very deliberate in selecting antibiotics that are necessary and will be effective. With our approach, physicians would still need to treat broadly with the first dose of antibiotics, but this new testing platform could inform the second and future doses of antibiotics, to more precisely target the infection.

How is your approach different than current practice?

The current approach to diagnosing septicemia -- bloodstream infection --is based on growing a culture from the blood, which takes days. Typically, the blood sample is sent to a lab where it is placed in a broth and watched to see if bacteria or other disease-causing germs grow.

We have found a way to directly test whole blood and diagnose bloodstream infections without the need to grow a culture. That means the test can be done near the patient bedside, and the first results -- information about possible bacterial infection -- would be available to the physician in a fraction of the time.

Can you explain your approach in more detail?

We analyze bacteria at a single-cell level versus an entire population of cells. To work at such a minute scale, we are using advances in "microfluidic" technologies, which is the manipulation of tiny amounts of fluids. These technologies enable us to miniaturize a full-scale laboratory into a disposable, cartridge-size device operable by a bench-top instrument.

In addition, we are combining advances in molecular microbiology, computer science and microscopy to quickly detect and identify the specific bacteria in the bloodstream and determine what antibiotic might be most effective in fighting it. Essentially, our test first captures live bacteria directly from whole blood, then probes the genetic sequences within each bacterium individually for species identification. We then track phenotypic features of individual live bacterium -- size, shape, metabolism and growth rate -- to determine the response to antibiotics.

Despite incorporating these complex technologies, we want the end product to be automated and easy to operate. Hopefully this can be done within the timeframe of emergency care -- and ideally closer to the patient bedside. Most important, we want to make sure that it greatly improves patient outcomes.

Has COVID-19 influenced your work or thinking in any way?

As a clinician and a human being, I feel a mix of emotions. On one hand, COVID reminds us that we needed to do better in preparing for emerging infections, and reinforces the importance of developing better diagnostic technology. So, in a sense, it validates the work I've been doing, and it's reinvigorating to continue down this path.

On the other hand, it has taken a huge toll on patients, family and friends. It is a reminder that these types of pandemics -- and maybe even worse ones -- are going to happen again in the future; and we need to be able to address them. We need to be better prepared through research in diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines and infection control strategies.

Image by SOPONE