A team of undergraduate bioengineering students from the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign has developed a device that could save the sight of millions of people in rural Central Africa. Their target: onchocerciasis, or river blindness, a parasitic disease endemic to that area that causes severe itching, skin lesions and debilitating vision loss.

The students -- Claire Lamadrid, Clay Ellington, Julia Schaepe, Kelsie Wysong, and Marissa MacAvoy -- came together in Bioengineering Senior Capstone Design. In the project-based course, students work in teams to identify real problems in health care and develop novel, technology-based solutions.

The teams are advised by Stanford Medicine clinicians, as well as engineering faculty, teaching assistants and industry experts. One of the river blindness team's mentors was Manu Prakash, PhD, associate professor of bioengineering, whose research interests include inventing low-cost science tools to democratize global access to science.

Common cause of infectious blindness

Onchocerciasis is one of the most common causes of infectious blindness in the world; an estimated 20 million people have the disease and another 125 million live in at-risk areas.

Onchocerciasis is spread by infected blackflies found near fast-moving water in tropical climates. When the flies bite, they transmit microfilariae (worm larvae) that make their way into the skin and eyes. This causes intense itching, disfiguring skin nodules and eye lesions. The severity of the symptoms worsen over time, as larvae mature into adult worms that live 10 to 15 years and produce millions of new larvae.

While available treatments kill larvae and relieve symptoms, they do not kill adult worms. As a result, patients must be regularly monitored so treatment can be repeated.

As the Capstone team dug into the research, they homed in on diagnostics as a key problem.

"The standard means of diagnosis is to take skin snips from six different areas of the body and look under a microscope for microfilariae to emerge," said Lamadrid. "It's a painful, invasive test, and it has a 40% false negative rate that is even higher if the infection is in its early stages, meaning there are fewer of the worms to detect."

Detecting the disease with blue light

The team set out to develop a less-invasive, more accurate way to diagnose and monitor patients. Their breakthrough came after they read a study that used blue light to transform the capillary beds of the fingernails into a noninvasive window into the bloodstream.

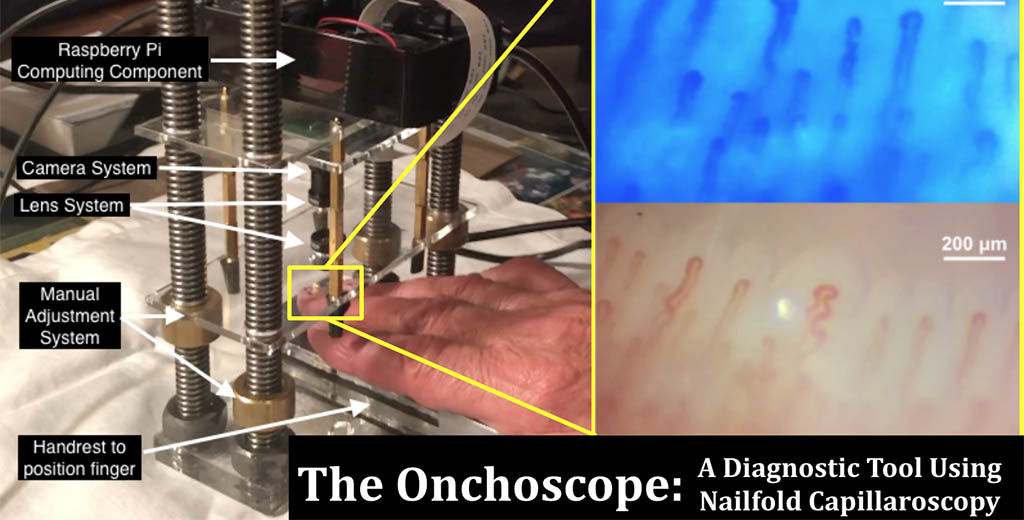

"In blue light, red blood cells appear dark, and white blood cells and the parasites we were trying to identify are optically clear," said MacAvoy. "So we decided to build a low-cost microscope that could detect the disease by using blue light to image the fingernail beds."

There was just one problem. "None of us had any idea how to build a microscope," said Wysong. "But we all learned together with some key guidance from Dr. Prakash, who connected us with folks in his lab to help us better understand the optics physics."

By the time the course was drawing to a close, the team had developed a working prototype of a device they named the onchoscope.

"The idea is that a health worker can use the onchoscope to image the patient's hand, then use our computer algorithm to get a yes/no diagnosis as well as a microfilarial count to accurately measure the parasitic load," said Lamadrid.

Continuing work on the project

But the team wasn't ready to stop when the class ended in the winter.

In early March, students applied for and won funding from Biodesign NEXT, a program offered through Stanford Biodesign that provides additional funding and mentorship to teams from select biodesign courses. Three of the five teammates -- Lamadrid, Wysong and MacAvoy -- continued working on the project on their own time.

Their goal was to use the funding to do laboratory testing in the Uytengsu Teaching and Learning Labs in preparation for human testing. However, COVID-19 upended their plans.

"Since we no longer had access to the lab, we decided, instead, to build more prototypes at home and focus on improving reproducibility and ease-of-use," said Lamadrid. "While we're not able to take this all the way to patients, we hope that someone else will. Accordingly, we're also creating a toolbox and manual to make it easy for others to hopefully bring the project to fruition in the future."

A prize and funding

In late August, the team learned that the onchoscope had won the top prize, and $20,000 in funding, in this year's DEBUT competition. Sponsored by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and VentureWell, DEBUT challenges students in undergraduate biomedical education to solve real-world health care problems.

"The team did an outstanding job of responding to both the problem and its context by developing a solution that could be assembled and used by community health workers, using affordable, off-the-shelf parts in a low-resource setting with minimal training," said Capstone course leader and lecturer Ross Venook, PhD, who is an assistant director of engineering at Stanford Biodesign.

Despite not reaching their stretch goal of on-the-ground testing in Africa, the teammates said they found the experience gratifying.

"We learned so much," said MacAvoy. "You have to spend time developing a deep understanding of the need, and this was something our team really leaned into."

Image by Kateryna_Kon