Early on the morning of March 3, I got a call from my editor: "It sounds like Stanford is about to launch its own COVID-19 test. We need a story."

I spent frantic hours gathering more details and interviewing infectious disease specialist Benjamin Pinsky, MD, PhD, about the research coming out of his lab.

The next day, Stanford Medicine became one of the first academic medical centers in the country to offer a test to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

I described it in a breaking news article and in more detail in my latest story for Stanford Medicine magazine.

Understanding the virus

Quick thinking and decisive action by Pinsky and his colleagues provided an important tool for managing the COVID-19 outbreak, just as it was beginning to hit California and days before the World Health Organization declared the pandemic. As Pinsky explained in my article:

The rapid implementation of the tests developed at Stanford allowed us to better understand the evolution of the pandemic in the Bay Area and California. It informed our governor and other decision-makers as they established our first shelter-in-place orders, and it limited the initial spread of the infection in the Bay Area.

The article traces the development of the diagnostic test meant to detect active coronavirus infection; it also recounts how Stanford scientists created another test meant to identify antibodies in people who had previously been infected.

This test, called a serology test, is an important way to track the spread of the virus through the population. Pathologist and immunologist Scott Boyd, MD, PhD, and his colleagues, including postdoctoral scholars Abigail Powell, PhD, and Katharina Roeltgen, PhD, developed the test in a matter of weeks.

Around-the-clock research

"During the last two weeks of March, Katharina and I were working 16-hour days," Boyd told me. "Each round of experiments takes four or five hours, and then we'd tweak some conditions and try again. It was a period of intense work."

James Zehnder, MD, director of clinical pathology at Stanford Health Care, summed up the frantic days of March and April this way:

Despite the pressure, the idea of not delivering the tools our physicians and researchers needed to care for our patients and employees never came up. There has been a sense of, 'This is what we were trained to do, and we will make it happen.'

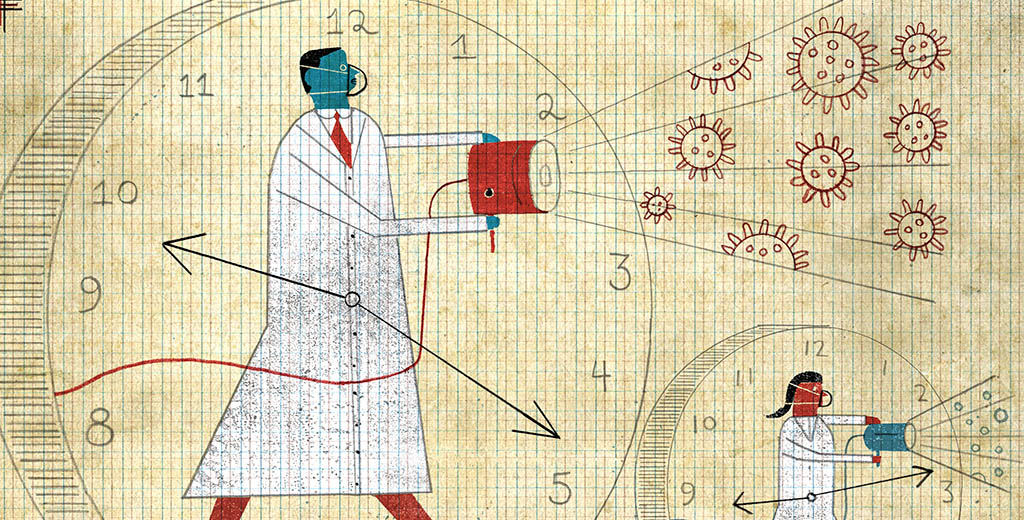

Image by David Plunkert

Read more from Stanford Medicine magazine's special report on COVID-19 here.