As more children and teens with diabetes use technology to treat the disease, U.S. kids of lower socioeconomic status are being increasingly left behind. They have more difficulty getting the latest diabetes treatment devices, so they miss out on the best ways to manage their blood sugar levels.

These findings are from a new Stanford Medicine-led study that appeared recently in Diabetes Care. The research included about 16,000 children and teens in the United States and nearly 40,000 in Germany. All have type 1 diabetes, which interferes with the body's production of insulin, a key hormone needed to metabolize sugar.

"Kids who are less socioeconomically well off are doing worse now than they were a decade ago," said lead study author Ananta Addala, DO, MPH, a Stanford Medicine scientist and a pediatric endocrinologist at Stanford Children's Health. "It is a problem that needs to be fixed, because it's only getting worse."

The study, which looked at young diabetes patients in 2010-12 and again in 2016-18, highlights the built-in inequities of the U.S. health care system, the research team said.

For instance, in 2010-12, few young patients in either country were using continuous glucose monitors, which track patients' blood sugar around the clock. By 2016-18, about half of German patients across all socioeconomic groups were using this technology, but in the U.S., those rates of use were achieved only by the best-off kids, while just 15% of the least well-off children were using the devices.

"The data from this report indicate that disparities in access to diabetes technology have increased in the United States over the past decade, in contrast to what we see in Germany," said the study's senior author, pediatric endocrinologist David Maahs, MD, PhD. "It was disappointing to see how much the disparity had increased over time."

Technology eases disease burden

Having type 1 diabetes is a lot of work. Children and their families must keep tabs on the child's blood sugar levels, calculate carbohydrates in the foods they eat, inject proper insulin dosages and stay alert for symptoms of dangerously low blood sugar.

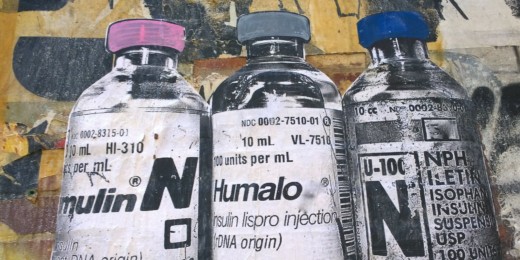

Since 2010, diabetes treatment technology has improved dramatically. For one thing, continuous blood glucose monitors have become much easier to use. The monitors rely on a small sensor implanted into the patient's skin that transmits frequent updates on blood sugar levels to the person's phone, saving them from pricking their fingers for blood samples several times a day.

This reduces the logistic and psychological burdens of living with diabetes, and improves family relationships for young people with the condition. (Parents no longer need to nag teens to check their blood sugar, for instance.) It also helps patients maintain healthier blood sugar levels, prior research has shown.

But the monitors are expensive and in the United States, patients in lower income brackets with public health insurance often have trouble getting their costs covered.

With U.S. public insurance, coverage for the devices varies not just from state to state but also from county to county, and obtaining coverage involves many bureaucratic hurdles and delays. These same young people also tend to experience frequent interruptions in insurance coverage for diabetes technology, making it harder to control their blood sugar, prior Stanford research has shown.

In this country, racism also factors into who can get diabetes technology, an editorial accompanying the new study points out. A 2015 study of insulin pumps, another important device in diabetes care, showed that among children whose parents had college degrees, twice as many white children as non-Hispanic Black children were treated with the pumps.

The disparities are especially worrisome because diabetes technology keeps improving, Maahs said. Recent research has shown that continuous glucose monitors can be linked to insulin pumps to make kids' treatment even more automated, but that's good news only for patients who get the new devices.

Turning disparities around

Addala is concerned that, without a focus on reducing the gaps created by socioeconomic and racial inequities, disadvantaged diabetes patients will fall further behind. For instance, diabetes providers can unwittingly contribute to the problem when they don't offer the latest devices to patients with public insurance, she said.

Providers hate to offer something they think patients' insurance might not cover, Addala said. "This is well-meaning, but misguided because diabetes technology is covered by most public insurance," she said. "Ultimately, this mindset leads to a greater systemic disparity."

Addala plans to focus her research career on reducing systemic medical inequity so all young diabetes patients can equally benefit from using the latest and best treatments.

"We need to think about how we re-engage with vulnerable populations who have been historically marginalized by medical communities," she said.

Photo of a continuous glucose monitor by Shutterstock