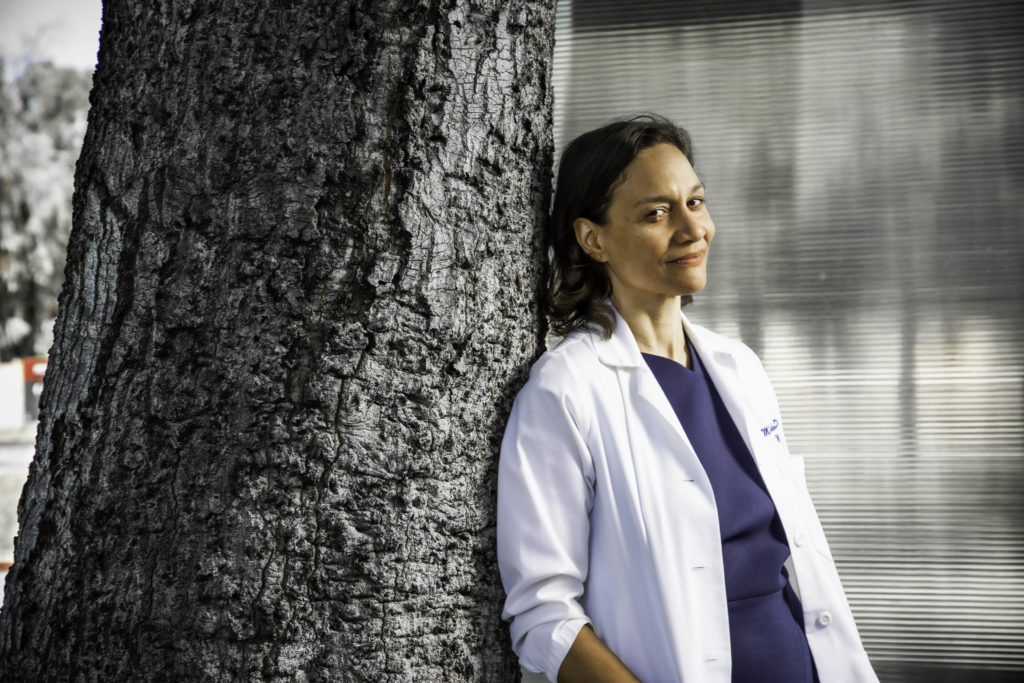

For much of her adult life, Megan Mahoney, MD, was categorized as "other." Her father was an Irish-American priest, and her mother a Black college president. She did not fit into any neat racial categories.

When it came to her medical care, she realized while she was in medical school, her treatment could depend on how clinicians chose to categorize her race. Whether she was considered white or Black could affect the measurement of her lung function, the dosing of her medications and whether she could qualify for a kidney transplant, among other things.

"You can have the same (patient) case, the same words or presentation, and once you attach white or Black to it, you will see different recommendations," Mahoney told me.

In a recent story, "Unequal treatment," for an issue of Stanford Medicine magazine, I describe just how much racial bias is embedded in clinical care, research and training and how this can harm non-white individuals.

Among the many examples I cite is the standard measure of kidney function, which is automatically adjusted upward for Black patients. This is based on the slavery-era myth that Blacks have greater muscle mass, said Mahoney, a clinical professor of medicine and chief of staff at Stanford Health Care.

The result is that a Black patient may be classified as having less severe kidney disease than a white person, thus disqualifying him or her for a kidney transplant or causing a delay in treatment that could be harmful.

Classifications could sabotage care

The 2020 racial justice protests and the coronavirus pandemic, which disproportionately affected minorities, brought these disparities into relief. As a result, clinicians are starting to look at ways to correct them.

The American Medical Association led the way with a statement in late 2020 declaring racism to be a public health threat and urging practitioners not to use race as a proxy for biology or genetics in clinical care, research and education. Rather, the statement said, the focus should be on the many other social factors -- such as housing, environment, education and employment status -- that collectively play the greatest role in our health.

"When race is described as a risk factor, it's more likely to be a proxy for influences of structural racism than genetics," Baltimore internist Willarda Edwards, MD, and a board member of the association, told me.

"It should not be a sole relevant factor in clinical situations. Race alone doesn't contribute meaningful information."

Changing training to address disparities

Stanford Medicine has followed suit with the creation of its Commission on Justice and Equity to find ways to make the culture more diverse and equitable and to address health disparities at the local and national level. The School of Medicine is also overhauling its curriculum so trainees learn to consider the broad spectrum of social and environmental factors, rather than race, that shape an individual's health.

"We teach the biology of disease very, very well," said Daniel Bernstein, the Alfred Woodley Salter and Mabel G. Salter Endowed Professor in Pediatrics. "But as the World Health Organization has noted, about half of the contributing factors of a patient's health are not related to biology. ... If students are only learning about 50% of health, they are missing a huge opportunity."

Image by Brian Stauffer