In the early days of COVID-19, Stanford Hospital cook Hilda Fabian could look in her customers' eyes and tell that the health crisis was taking a toll. She prides herself on bringing joy to those she serves, from the surgeons to the nurses to the CEO of Stanford Health Care. She was worried about them.

"I could see they were tired. ... We were all sad about what was happening," said Fabian, an accountant turned cook who has worked at Stanford Health Care for nearly a decade. "I had to do something to make them happy."

Fabian, who trained in San Francisco restaurants and in dining services at Apple, had an inkling that a certain dish of hers could put a smile on employees' faces.

The comfort of home-cooking

With the support of Stanford Health Care food services director, Jodi Krefetz, Fabian stood at the entrance to the hospital cafeteria one Thursday in April 2020 and introduced customers to her late mother's chilaquiles, a celebratory Mexican breakfast made with house-made crispy tortilla chips simmered in red and green salsas and served with cilantro, crumbled cheese, sour cream and avocados on top.

For the Stanford crowd, she adds eggs or chicken for a heartier meal. The centerpiece is her salsa, made with five cases of tomatoes and chili peppers that she roasts two days ahead to give enough time for the flavors to marinate and develop.

"I knew that if I made the salsas, that would bring more people into our cafeteria and give them a little bit of happiness, with how hard they were working," Fabian said.

With the pandemic, everything had changed for the 300-plus member hospital food services team, seemingly in an instant. Pivot was the word they lived by. Suddenly, there was a halt to catering, gatherings or events. Because there were food shortages, the staff made frequent adjustments to patient meals, making sure each substitution met patients' nutritional requirements.

Drawing strength from each other

No visitors were allowed in the cafeteria. Self-service food service ended, with dedicated staff providing every cup of coffee and utensil. It was an anxious time, but the dining employees showed up each day and drew strength from each other, Krefetz said.

"There were nerves, and some fear, and lots of emotions running for a lot of people, but we could continue to provide that place of respite," Krefetz said. "The people who work here are absolutely phenomenal -- full of heart, full of soul, full of resiliency."

Fabian told a few regulars about her plan to bring a taste of her home to the hospital, and word spread quickly about her Thursday chilaquiles.

"The first day I opened the station, I sold maybe 170 plates. People starting telling other people, and more people started coming in," Fabian said. "They were coming, dancing, and putting their hands up and saying, 'Hilda, always making a party for me.' They made me cry because I was happy to see them happy. ... They told me I was healing them with my food."

The chilaquiles brought people together safely for a few moments each week. COVID-19 might have taken away their ability to sit and share a meal, but standing in that socially distanced line, hospital employees connected with one another.

"For those two minutes you're waiting in line on Thursday mornings, you get to say, 'How are you?' You get to smile with your eyes. ... It gives you that moment of rejuvenation," Krefetz said. "This dish completely represents how we were able to get through this time period."

These days, Fabian makes close to 280 chilaquiles each Thursday. Her station stays open from 6 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. -- sometimes later if she hasn't run out of food, because she doesn't like to turn anyone away.

Each dish is made to order. Spicy or mild; eggs or chicken; green salsa or red; in most cases, she doesn't need to ask. She can look down the line and keep orders for 10 people in her head, so when they get to her, the food is already ready. She leaves the containers open because her customers like to take pictures of the food to post on social media.

An appreciative audience

Fabian's customers make her feel like a celebrity chef. They ask to take photos of her and her station, which she dresses up with Mexican blankets and other items her mother bought her in Mexico. They request the recipe so they can try to replicate the dish at home (it is never the same, they admit to her.)

Some speak Spanish with her, and want to know more about her life. Fabian said one nurse told her she wouldn't change shifts -- she works through the night so she can have the chilaquiles.

For people coming off the overnight shift who want to share the dish at home with their spouses, Fabian puts the salsas on the side so the tortilla chips won't get soggy.

By the end of the Thursday breakfast period, Fabian and the team are filled with pride and gratitude, despite the amount of effort involved in preparing this beloved offering. Fabian's arm hurts, and she has walked about 45,000 steps. But her heart is full.

"Like I tell my customers -- they always ask me what is the special ingredient that I put on my chilaquiles," Fabian said. "I tell them, love, because when you do something with love, everything is going to come out beautiful."

Photos and video by Kevin German/Luceo

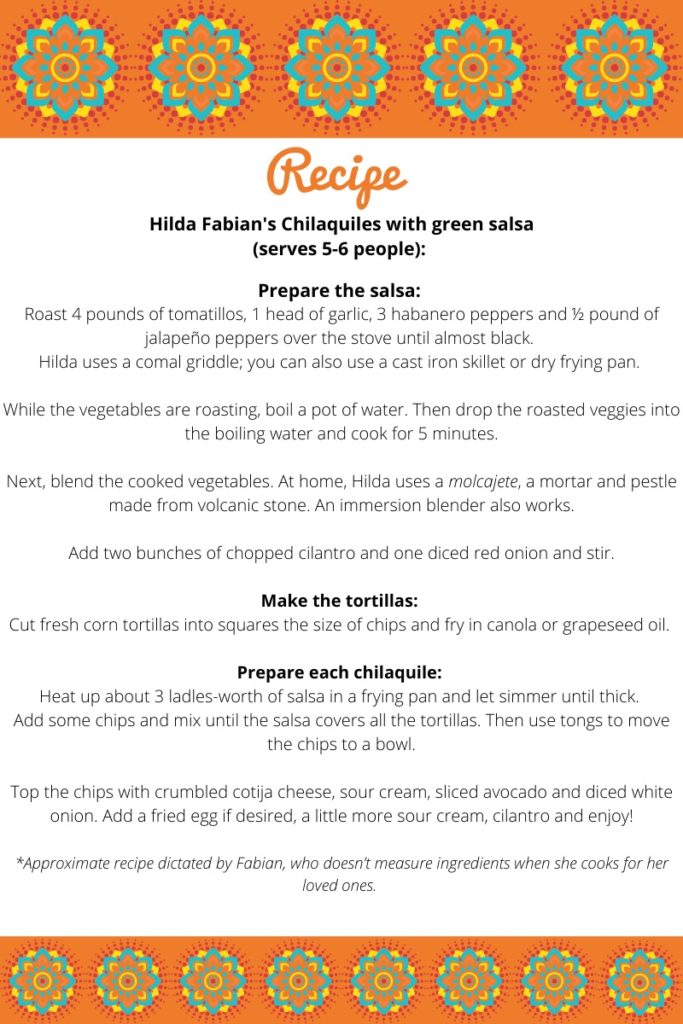

To download a copy of Hilda Fabian's Chilaquiles recipe click here.