When Arjun Rustagi traveled to Southern California in January 2020 to learn lab safety protocols for contagious and potentially lethal pathogens, he didn't know that he'd soon be applying his training to a virus so threatening it would shut down the world.

Rustagi, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in infectious diseases and geographic medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine, had investigated viral infections for most of his career. So it felt like a natural continuation to study dangerous airborne pathogens upon joining the lab of Catherine Blish, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, in 2019.

Now, Rustagi's expertise has placed him at the center of Stanford Medicine's effort to study SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. He and others are trying to understand the basic infectious nature of the virus and how it morphs into new variants, and they're looking for treatments that can stop the infection before it causes severe or lasting damage.

Pivoting to SARS-CoV-2

At the beginning of 2020, Rustagi had decided to focus his lab work on tuberculosis and Valley Fever, requiring him to be trained and certified to work in Biosafety Level 3 labs, which are designed to safely accommodate studies of dangerous airborne pathogens. While at the training facility, he and other infectious disease researchers began hearing of a new virus threatening Wuhan, China.

"The Johns Hopkins tracker had just started, and we were beginning to see cases in China," said Rustagi. "The person facilitating the training actually researched coronaviruses, and he briefly mentioned that something was up with a new coronavirus in China. But we were mostly just focused on the training."

Back at Stanford, Blish was also keeping tabs on Wuhan. "I began to worry that cases were going to spread," said Blish. "We had jumped on research when Zika emerged and we were able to contribute some important work early on, so I thought we should be ready to go in case there were infections in the U.S."

Within a couple weeks of Rustagi returning to Stanford, the campus' entire research enterprise was shut down by COVID-19. That is, save for Blish and Rustagi's new charge: Devise a protocol for handling SARS-CoV-2 in the lab, parts of which would later be integrated into California's official guidance for researching the virus.

After establishing approved safety protocols for SARS-CoV-2 research in March 2020, it was time to get to work.

"Back then, we didn't have a vaccine, we didn't have treatment, we didn't even know how to test researchers for exposure," said Rustagi. It was a brand-new virus that no one knew anything about and answers were urgently needed. How did it transmit? Which cells were being infected? Were there drugs that could treat it?

At the time, Rustagi was one of the few scientists in the state prepared to answer any of these questions. Sheathed in layers of personal protective equipment, he started by obtaining a sample of SARS-CoV-2. It turns out, for a small fee -- and special clearance granted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention -- you can order a vial of SARS-CoV-2 in the mail. "It's only 20 bucks," said Rustagi. And they deliver it overnight.

Research and safety in the bubble

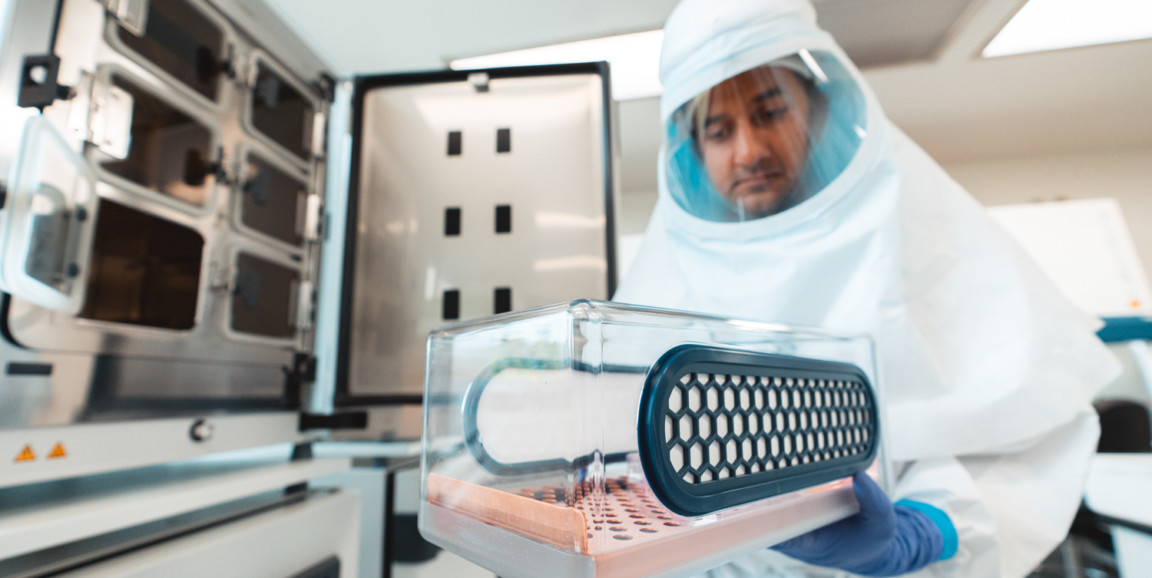

When Rustagi began his research, Stanford didn't have a formal Biosafety Level 3 lab, so he worked out of a 'bio bubble' -- a temporary hyper-hygienic zone built to contain hazardous research that was originally constructed for tuberculosis research in the lab of Blish's colleague Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, professor of chemistry. For several months, Rustagi conducted experiments in the bubble.

Among his investigations: He modeled SARS-CoV-2 infection in lung organoids to see how the virus latched on and forced entry into cells, and he performed drug screens to search for molecules that could help fend off severe disease.

It was hard work made even harder by a particularly uncomfortable dress code. "We had this head-to-toe PPE jumpsuit. We called it 'the spacesuit,'" said Rustagi.

The full-body jumpsuit had a front-zipper protected by a spill-proof flap, a respirator that sits on the hip and connects with a face mask that looks like a space helmet, as well as sleeve protectors and multiple layers of booties and gloves.

"It takes a good 20 minutes to get it all on, so if you need a sip of water or have to use the bathroom, you have to budget about 45 minutes." Not to mention if you get an itch or, in Rustagi's case, get a tickle in your sinuses. "I sneezed once and it sprayed the inside of my face shield. It's not like you're going to take 45 minutes just to wipe it off," said Rustagi. "So it just sat there, like a dirty windshield."

The bubble was designed to keep any research specimens contained to only that space, with other decontaminating areas surrounding the bubble so Rustagi and other bubble researchers could peel off dirty layers in an area that wouldn't expose others.

"We were kind of on the edge of what was known, so we had to take extra steps to maintain safety," said Rustagi. Part of that involved buddy system Rustagi used with other researchers who had been studying tuberculosis in the bubble. "If you feel like something isn't right or you're concerned about something that happened, you talk it through with your buddy and come to a conclusion about whether you're still safe and can keep going."

This was how Rustagi worked until June 1 last year, at which point, Stanford began construction on its first Biosafety Level 3 laboratory in an existing building on campus.

Leveling up

Between data analysis and Zoom calls, Rustagi and Blish helped guide the new lab's development. "My lab was particularly well-suited to drive this effort because we're really interested in the host-immune response to pathogens and we work with multiple viruses. So I had a lab of viral immunologists with BSL3 training and we needed a place for them to work," Blish said.

Nudged by the urgency of the pandemic and with support from Dean Lloyd Minor's office, Blish and researchers from the Stanford Innovative Medicines Accelerator, pulled together the funding and manpower to create a state-of-the-art Biosafety Level 3 lab -- in a matter of months. "I think that was probably some kind of world record for a BSL3 lab," said Blish. By October, the building was ready for action.

"My entire team has been amazing during this pandemic, they've been working with the virus long before we had a vaccine, and before we even really knew the best way to work with it," said Blish.

"Arjun, in particular, was putting in 120-hour workweeks while wearing a spacesuit, and he has been aided by a huge number of people in my lab. I'm really grateful to my entire team for stepping up and working incredibly hard under incredibly challenging conditions to build and operate this new facility, which now everyone can use with proper training."

The work continues

With new-and-improved safety features -- including negative pressure rooms that ensure air flows only into the lab, and automated doors that open strategically to contain potentially contaminated air to specific spaces -- Rustagi and others he trained to handle SARS-CoV-2 returned to campus after a construction hiatus to restart their research.

It's been more than a year since the beginning of the pandemic, and even as Rustagi and his colleagues learn more about the virus, many unknowns remain.

"Those initial questions about how infectious the virus is and how deadly it is are still relevant, particularly as we see new variants come into play," he said. "There's still so much that we don't know, there's still a lot of basic questions to answer in the lab."

On a personal note, Rustagi said that applying his expertise to something like SARS-CoV-2 has been rewarding in its own way. "For any disease, it's important to understand why some people get sick or die, but to be able to contribute to that understanding for an urgent public health crisis -- and hopefully help bring it to an end -- is a rare opportunity."

Top photo: Arjun Rustagi, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in infectious diseases and geographic medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine, carries human lung tissue into the bubble to infect it with SARS-CoV-2 to study the earliest events of infection. (Photos by Andrew Brodhead)