In early 2020, as COVID-19 began to make headlines around the world, Ashley Styczynski, MD, was in Bangladesh conducting research on antibiotic resistance within hospitals. But as an infectious disease fellow at the Stanford University School of Medicine, her eyes were on the news.

By mid-March her research was on pause. Bangladesh reacted to the pandemic swiftly and severely. The country was quickly shutting down around her and, back in Palo Alto, California, Stanford Medicine had sounded the alarms -- all traveling students, staff and faculty were ordered to come home immediately.

"It was fairly dramatic. One day, you're out on the busy streets of Dhaka, where there's tons of traffic, and the next day, the streets are dead silent," said Styczynski. "Nobody was going outside. Nobody was going to stores. There were even police stationed outside to make sure people were traveling only for valid reasons."

Still, Styczynski stayed put, through the shutdown and, soon after, through border and airport closings. Styczynski had worked with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an epidemic intelligence service officer investigating disease outbreak, so she petitioned Stanford to stay in Bangladesh.

Protection equipment desperately needed

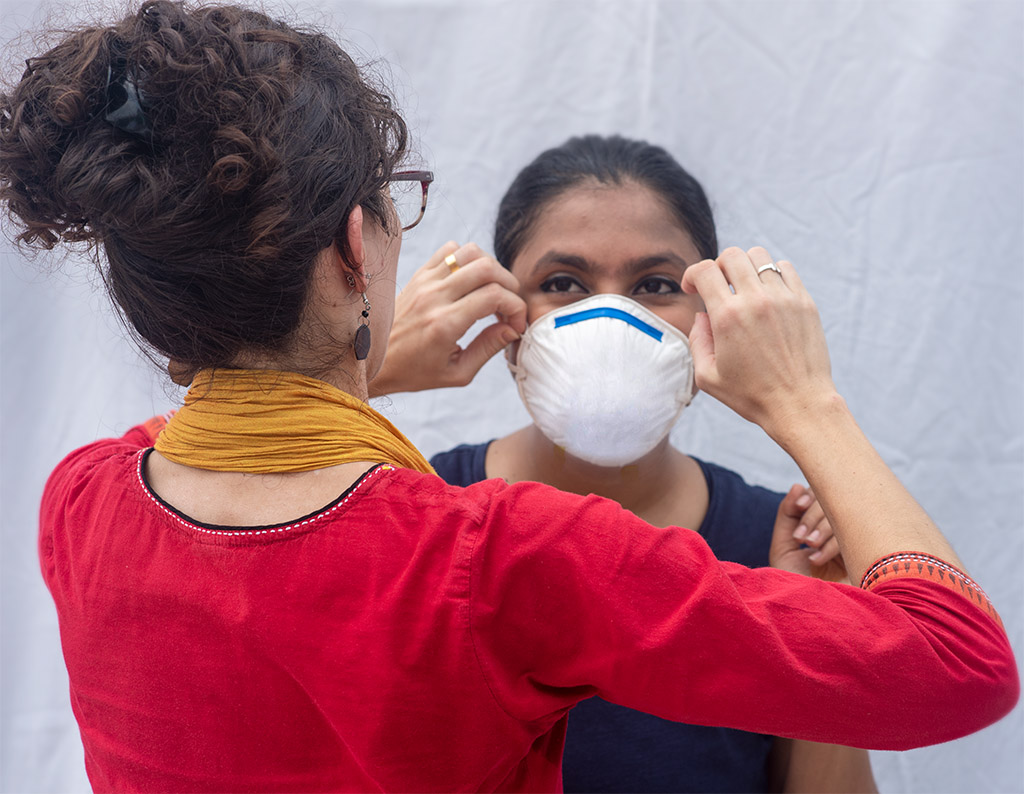

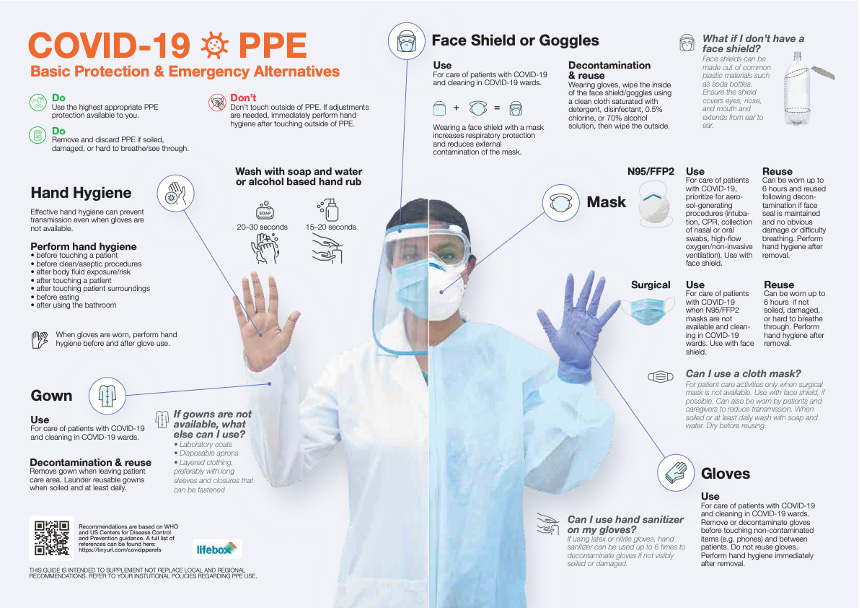

As COVID-19 patients started showing up in hospitals, Styczynski joined a team from the CDC and the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research in Bangladesh to train health care providers on infection prevention and control, as well as proper use of personal protection equipment, or PPE, such as masks, face shields, gowns and gloves.

These providers were at serious risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection not only because local hospitals lacked the necessary PPE but also because protocol guidelines were inadequate and inconsistent.

"They needed PPE but they also needed instruction around evidence-based use of it," Styczynski said, noting that, early on, health workers were wearing excessive PPE that could increase the risk for self-contamination.

But because of the supply shortage and knowledge gap, she saw people making desperate attempts to protect themselves. Doctors, for example, would come in wearing rain jackets and ski goggles under their face shields in humid, 80-degree-plus heat.

Styczynski saw an opportunity. Working with her adviser, Stephen Luby, MD, a Stanford professor of medicine, she laid the groundwork for a project that expanded the understanding of PPE decontamination and reusability in low-resource settings and developed ways to clearly and effectively communicate proper PPE use to the health workers.

Improving protocol and training across the board

At the same time, researchers at the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health were rushing to release a new round of seed grant funding for creative projects that might bolster COVID-19 relief efforts.

"We knew this project stood to have unique impact," said Michele Barry, MD, director of the center and the Drs. Ben and A. Jess Professor of medicine.

"All over campus, academics were working on COVID-19 solutions for low- and middle-income countries, but very few people had the invaluable insights gained from having someone on the ground."

Working with Manu Prakash, PhD, associate professor of bioengineering; Thomas Baer, PhD, executive director of the Stanford Photonics Research Center; and Thomas Weiser, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery, Styczynski assessed the PPE recommendations Bangladesh hospitals were using.

The team assembled a PPE infographic that was translated it into multiple languages; disseminated to area hospitals; and, eventually, incorporated into the Bangladesh Ministry of Health's coronavirus infection, prevention and control guidelines.

Building a case for low-cost solutions and PPE reuse

Styczynski also collaborated with Baer to develop training materials for safe reuse of N95 masks using short-wave ultraviolet decontamination units that could be constructed in low-resource settings, which were replicated in more than 13 countries.

The team also tested non-medical masks for patients and people in the community. What they found was surprising: Surgical masks, which cost around 5 cents each, performed much better than the cloth masks they tested, even after the surgical masks were repeatedly washed.

"After an initial wash, there was a slight drop in filtration efficiency," Stycynski said. "It went from about 95% to about 75%, but this was still well above any cloth mask that we tested."

After 11 months, Styczynski headed home, but the research continues: The mask filtration research was included in a study on the breathability and filtration efficiency of common household materials for face masks, published in July in ACS Nano. Other research, including on the extended use of exam gloves, is under review, along with two other papers.

"PPE shortages are a norm in many low-resource settings, but the problem has been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence-based strategies for decontamination and reuse of PPE are imperative for protecting health care workers beyond the current pandemic," Styczynski said.

"We wouldn't send firefighters into a burning house without the appropriate protective gear. Health care workers are the frontline defense against many diseases, and they deserve to know how to protect themselves as well."

Top photo shows the set up used to evaluate the impact of sanitizing agents on the integrity of surgical gloves in Ashley Styczynski's PPE research in Bangladesh. (Research images courtesy of Styczynski.)