What might a minute organism in pond scum have in common with SARS-CoV-2? Not much, but both do contain a genetic element scientists have long wanted to view up close, in fine detail. Now, using a tandem microscopy and computer-powered approach, Stanford researchers have succeeded in doing just that.

Specifically, the team has been peering at molecules of RNA, a close relative of DNA that often acts as a translator of sorts between an organism's genetic code and the proteins it makes.

The more scientists can zoom in on a given RNA molecule, the closer they can examine every little nook and cranny, which may help them better understand how the related organism or virus works. Doing so in 3D is even better, according to a recent SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory article describing the research.

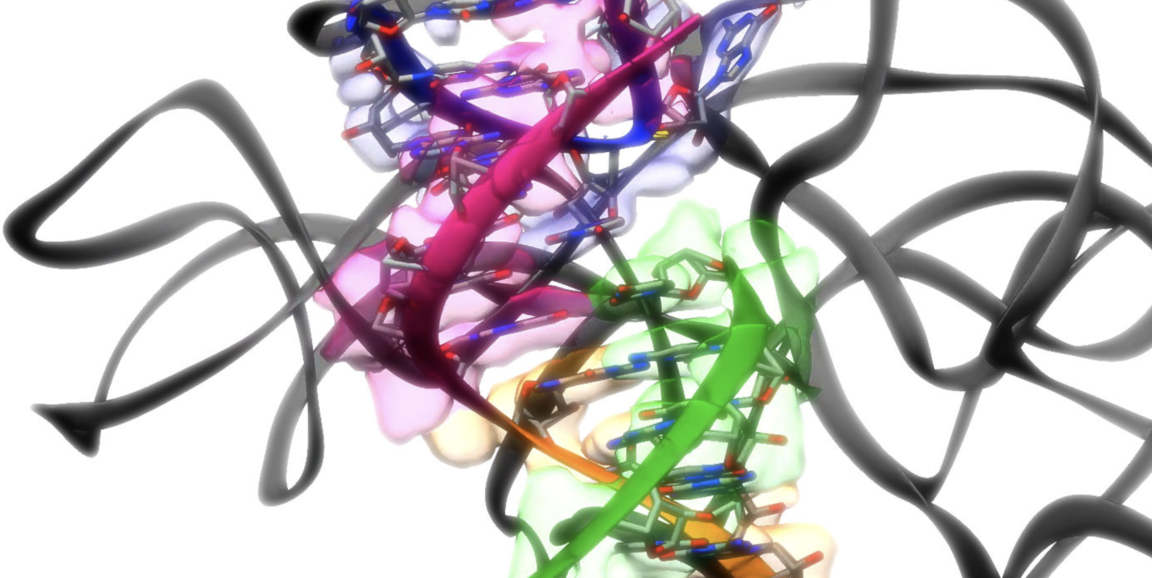

As such, Wah Chiu, PhD, professor of bioengineering, and Rhiju Das, PhD, associate professor of biochemistry, and their research teams built a system to speedily churn out detailed 3D images of various RNA structures. The Stanford Medicine researchers collaborated with researchers at SLAC, where Chiu is also affiliated, to develop this RNA pipeline, dubbed Ribosolve.

It makes use of cryo-electron microscopy, a Nobel Prize-winning method that involves flash-freezing a sample from a biological molecule of interest, then bombarding it with electrons. Next, a special camera captures 2D pictures from multiple angles, which are aligned into a 3D map, giving scientists an intimate look at that molecule's features.

RNA, ready for its close-up

In a study published Aug. 11 in Nature, Chiu and Das described using Ribosolve to reveal new structural information of a piece of RNA from a teeny critter, Tetrahymena, that commonly dwells in pond scum. To scientists, this little piece of RNA is the prototype of so-called ribozymes, or RNA molecules that can spur chemical reactions. The Stanford crew imaged Tetrahymena's ribozyme at a resolution so high that they could almost distinguish its individual atoms.

In tandem, on Aug. 23 in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, the researchers also documented in-depth views of an RNA fragment from SARS-CoV-2. This part of the virus, called the frameshift stimulation element, does not change -- unlike other bits that frequently mutate and lead to variants such as delta -- and is therefore thought to be a good target at which to aim COVID-19 drugs.

Ribosolve showed that this stagnant viral element has teeny pockets, and Das's group, working with Jeffrey Glenn, MD, PhD, used this knowledge to figure out a way to undermine its important role in viral replication -- at least in the lab. It's an early but important step toward treatments that could universally target all variations of SARS-CoV-2, as Das notes in the SLAC article:

"We don't know what the next pandemic virus will be," Das said, "but we're pretty confident it will be a single-strand RNA virus transmitted from animals to humans, and it will likely have a few bits of RNA that resist mutation. With this accelerated system we've developed, it now seems feasible to study viruses found in humans or animals, look for those conserved bits, quickly determine their 3D RNA structures and develop antivirals against them."

This is edited and condensed from an article published by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Read the full story here.

Photo courtesy of the Das and Chiu research groups.