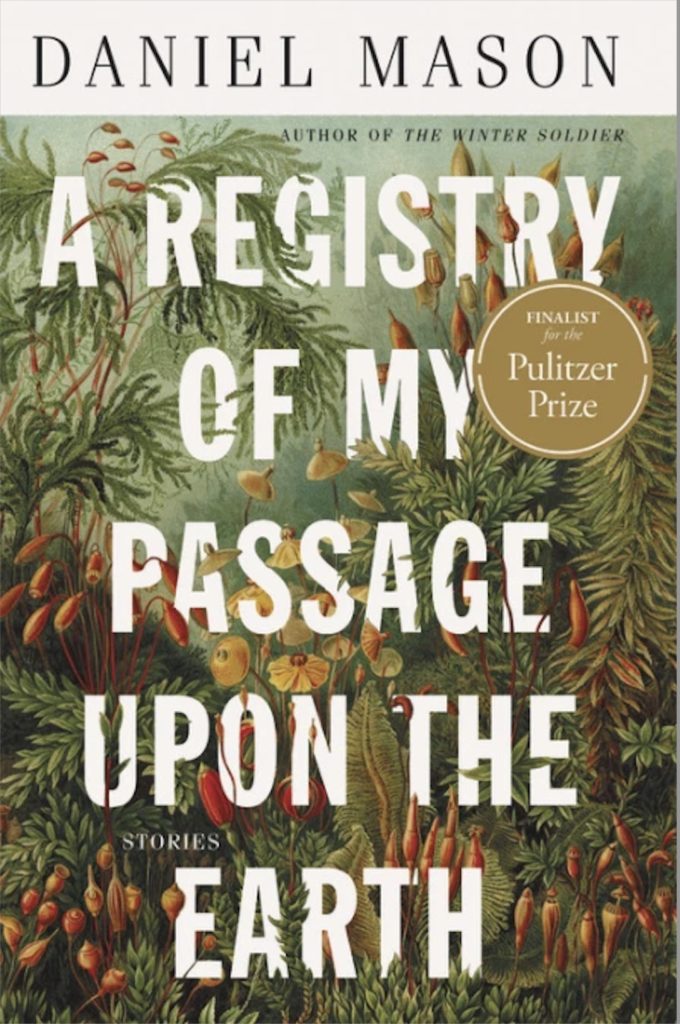

Author Daniel Mason, MD, a Stanford Medicine psychiatrist, recently captured the top fiction prize given by the California Book Awards jury for his latest book, "A Registry of My Passage Upon the Earth." Previous winners include such luminaries as John Steinbeck, Wallace Stegner and Joan Didion.

The collection of nine short stories, filled with lush scenery set in long ago times, explores such themes as the need for connection with each other and with the natural world. It was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in fiction this year.

Mason's career as an author began two decades ago when, during medical school, he wrote his first novel, the international best seller, "The Piano Tuner." He has since successfully combined dual careers as a novelist and as an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who researches, teaches and treats patients.

Mason was also recently awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship and is on sabbatical working on his next novel.

I asked him about how his two passions -- medicine and writing -- co-exist and what inspires his writing. This Q&A is condensed and edited for clarity.

You wrote 'The Piano Tuner' while in medical school. Did you set out to be both a writer and a physician?

I never really felt like I had a plan. I hadn't imagined that it might be published and really began it mostly as a way to explore ideas and images that I had encountered during a year of malaria research in Southeast Asia. But it turned out, writing was a wonderful way of thinking about what I was seeing in medicine (as it still is). It helped me explore questions of illness, meaning, connections between people.

How has your career in psychiatry influenced your writing?

Over time, both careers have interacted in unexpected ways. I often find that fiction informs my medicine as much as the other way around. Whether thinking about patients' stories in terms of narrative structures, or trying to pay closer attention to a person's material world or enter a character's inner world, these are all essential elements of fiction that also make up so much of a clinical encounter.

Your short stories suggest you are an explorer at heart. Can you tell us about some of your travels -- and how they helped shape your writing?

I began the first story in "Registry of My Passage Upon the Earth" in 2003, during a time when I was traveling a lot. Much of this was in Brazil, where I was working on a novel. But I ended up being wonderfully sidetracked in the Amazon, a trip that remains one of the most extraordinary experiences of my life.

I haven't left the United States in more than a decade now, though. So much of my "travel" has been imaginary. For example, I never had a chance to go to the mountains in Eastern Europe where my last novel, "The Winter Soldier," takes place.

But even when I'm writing about a distant place, I usually am drawing the inspiration from my own world. This is particularly true for "Registry," which deals with very Californian concerns -- from the effects of environmental degradation to the isolation brought about by technology.

I've read you have a respect for older literature. Can you elaborate on that?

As with travel, I've always found that history offers ways of exploring diversity of experience and making sense of where I am. But I am drawn to unusual language and narrative forms, particularly non-fictional texts like medical journals or older travel accounts.

For example, in the short story "Death of the Pugilist," I was captivated by the energy and rhythm of early 19th century boxing narratives, which use a vocabulary both familiar and utterly strange. I was excited in the same way a musician would be excited by discovering a new instrument -- one wants to play it and see what sounds it can make.

But I've come to wonder if this interest is also a way of exploring my English, seeking its precedents and thus serving as a kind of personal archaeology of the language that shapes my world and thoughts.

An astonishment for the natural world blossoms on so many of the pages of this book. What role does the environment play in your writing?

I've always been deeply drawn to the natural world. I grew up in California and spend a lot of time outdoors. But something happened in my late 20s, particularly on that trip to the Amazon, and suddenly the majesty of the natural world became apparent in an almost ecstatic way. This sense of awe has only grown, and several of the stories in the book were ways of exploring people who find themselves in awe at the beauty and wonder of the natural world.

This book is being published by Little, Brown and Company.

Photo by Dariusz Sankowski